Hello from the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Linguistics of English, or #ISLE5, as all the cool kids are tweeting it. We have an afternoon for touristic activities, but since we're in London, I'm feeling a combination of (orig AmE) 'been there, done that' and 'I could do that any time'. What's not available any time is a bit of quiet to blog. So, yay for everyone else going to Samuel Johnson's House (been there, got the postcards) and for my lovely hotel lounge and wifi. Today's post was started possibly years ago (I've lost track), when Lauren Ackerman asked me about British chilli versus American chili.

Hello from the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Linguistics of English, or #ISLE5, as all the cool kids are tweeting it. We have an afternoon for touristic activities, but since we're in London, I'm feeling a combination of (orig AmE) 'been there, done that' and 'I could do that any time'. What's not available any time is a bit of quiet to blog. So, yay for everyone else going to Samuel Johnson's House (been there, got the postcards) and for my lovely hotel lounge and wifi. Today's post was started possibly years ago (I've lost track), when Lauren Ackerman asked me about British chilli versus American chili.I went to my usual first stop: the Oxford English Dictionary. And I am sad to say that the entry for this item has not been fully updated since the first edition in 1889—which is to say, look at those spellings! (Not blaming them, just sad for my post that they haven't got(ten) to this one yet!)

Yes, chilli is still the BrE spelling for piquant peppers—but giving chilly as the alternative spelling and not the standard AmE chili reads very odd in the 21st century. Chili is acknowledged there as a historical spelling, and is present in the quotation evidence in the entry. And it's consistently been the more common spelling in the US:

|

| (click to enlarge) |

At the conference, I've been at two sessions where someone's called into question the OED tagline, visible at the top of the dictionary screenshot: 'The definitive record of the English language". That's marketing talk, not lexicographical talk, and it's unfortunate. There can be no definitive record of the English language, because there is no definitive English language. It's always varying and changing and you can never know if you've found the first instance of a word or the last one, etc. So here's a little plea (in the form of advice) to the Oxford University Press: If you put most before definitive it would be an accurate tagline. And it would have a marketing-department-friendly superlative in it! Win-win!

As a side-note, there's this little bit of puzzling prescriptivism in the run-on to the entry (i.e. the additional defined items at the end), which seems to have been added later—or at least I'm assuming so, given the AmE spelling (it's hard to tell, though, the link to the previous edition includes none of the run-ons).

I've been trying to figure out what that 'erron.' is referring to. I believe what it's saying is that the "real" meaning of chili pepper is 'pepper tree' and it's an error to use it to refer to chil(l)is, but why does it only have the US spelling? It's not clear to me when this chili pepper was added to the entry, as the link to the 2nd edition does not include all the compounds that are in the run-on entries. But it must be old, as it's not marked as a post-2nd-edition addition. But it's interesting to see how recent it is to say "chil(l)i pepper":

Anyhow, back to the word itself: it comes ultimately from Nahuatl, with an /l/ sound in the middle. We pronounce it with a 'short i' sound (like in chill). You can see, then why BrE likes the double-L spelling: without a double consonant, it looks like it should have a a different vowel: we say wifi differently than we'd say wiffi; fury versus furry, etc.

So why does AmE have a single L? My educated guess would be because Americans have had more consistent contact with Spanish. When the Spanish went to spell it, they used a single L, because double consonants don't do the same thing in Spanish spelling that they do in English. If you pronounce chilli in Spanish, there's no L sound. (What sound is there depends on your dialect of Spanish, but I learned in my US Spanish classes to pronounce the LL like a 'y' sound.) It stayed Spanish-ish in American, while getting a more English-ish spelling in Britain.

Now, I think that back in the mists of time when Lauren requested a post on chil(l)i, she meant the stew, rather than the fruit. I am not going to wade into the debates about what "real" chil(l)i (con carne) should have. But I will say this: every American I've seen to order the dish in the UK has had a moment of "Whaaaa?" when it was served with rice. Not something we're used to. But nice when you get used to it.

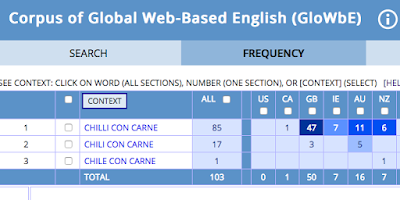

There is another spelling issue here, though. The pepper almost always ends with an i, but the stew sometimes ends with an e. But not much anymore, according to my corpus searches:

And on that note, I'll post this before my battery dies!

but why does it only have the US spelling?

ReplyDeleteWell, it seems logical to me if the only attested examples are in US texts using US spelling.

Be warned. The Preview function is not currently working. Worse, pressing the Preview button currently destroys the post.

ReplyDeleteSo, copy your text before trying to post. And if Preview is still not working, go straight to Publish.

This reminds me of the different pronunciations of the country "Chile". In the UK, when I grew up, it was invariably homophonous with "chilly". But in the US, it's more likely to be given a faux-Spanish pronounciation "chee-lay", which I've also heard making recent inroads in the UK.

ReplyDeleteThis is an example of the more general phenomenon of US English pronunciations being more likely to be Spanish-influenced, while UK English is more likely to be French-influenced, which I'm sure Lynne has covered elsewhere in her blog (great to have you back blogging, Lynne!)

Although sometimes spelt "chile", chili has nothing to do with the name of the country. The condiment exists in Chile, but its name is quite different: "ají". I pronounce Chile like "chilly" when talking with my relatives in England, but I pronounce it as in Spanish when talking to my (Chilean) wife or other Chilean people.

DeleteI grew up in the US and pronounce the country "chilly."

DeleteAjí is from Taíno, the language spoken on the islands where Columbus first landed. The Spanish learned that word first and it was established in colonial Spanish even before chili, which is why it's still used in South American and Caribbean Spanish.

DeleteWhen the Spanish went to spell it, they used a single L, because double consonants don't do the same thing in Spanish spelling that they do in English.

ReplyDeleteUp to a point. There are no double consonants in Spanish, apart from rr, and ll doesn't count as until 1994 it was treated as a distinct letter in its own right, different from l. In modern alphabetical orderings l and ll are no longer separated, but they're still regarded as separate in most people's minds. You're right that the spelling chilli in Spanish would give completely the wrong pronunciation.

Perhaps the spelling "chilli" is Welsh.

DeleteThat would be even harder to pronounce than most of the Spanish ways to pronounce "chilli". In Mexican Spanish, and many other dialects, "ll" has eroded to a "y" sound. In Colombian Spanish, other Andean dialects, and some parts of Spain, the "ll" is still pronounced with an "ly" sound - "millon" sounds like English "million" with the accent moved. Pronouncing "chilli" would be something like "chilyi".

DeleteIn Argentina, if you're over 45, "ll" is pronounced like English (not French!) "j"; if you're under 45, like "sh". So "chidji" or "chishi".

Athel, Anthony,

DeleteYour conclusions hold only if it's the case that Spanish never adopts spelling from other languages but always modifies the spelling to correspond to Spanish sounds.

I'm not suggesting that this isn't the case. I simply don't know. But it's worth making it explicit that Spanish differs from English and French in this regard.

David - in the case of "chili", the word was adopted from a non-alphabetic language, so the Spanish would have spelled the word to match the way they pronounced it. According to Wikipedia, the word comes from Nahuatl "chili", pronounced essentially the same way as in Spanish. Nahuatl doesn't have the phoneme corresponding to Spanish "ll", unlike some Andean languages, so it really wouldn't have made sense to use "ll" in "chili".

DeleteIn general, Spanish is (or used to be) *extremely* conservative - Colombian prescriptivists would spell "quilometro" because 'k' isn't a Spanish letter. These days, they're becoming more lax, to the point of officially renaming "i griega". But generally words that aren't proper names tend to be assimilated to Spanish pronunciation and Spanish spelling based on the Spanish pronunciation. Very recent borrowings from English are less likely to undergo this transformation.

Anthony, when I looked it up in Wiktionary, I found the very opposite.

DeleteIt's tucked away somewhere down the page, so here's a repeat of the relevant paragraph:

But no. According Wiktionary the Classical Nahuatl word was pronounced with a long L-sound. They offer two IPA transcriptions. One is tʃ͡iːlli but their preferred one is tʃ͡iːlːi which doesn't suggest a syllabic break between two L-sounds.

This explains why French and English have always used the -ll- spelling. English might have done so anyway, but French had no motivation to double the L: either spelling would be pronounced the same.

Living in New Mexico, it pains me to see you say "The pepper is[sic] almost always ends with an i, but the stew sometimes ends with an e.", which is entirely backward. We are, of course, famous for our Hatch Green Chile (peppers). If you really want to get someone's goat around here, try spelling it with an 'i' and watch their ears start to steam. 'i' can only refer to Texas Chili [con carne], the lesser of the chili/es.

ReplyDeleteYeah, I grew up (midwestern US, where black pepper is spicy, alas) calling them chili peppers, and was corrected enough upon moving out of the midwest that the peppers were "chile" and the dish was "chili" that I now also make that distinction.

DeleteChili powder is the mixed seasoning used for convenience, containing ground hot peppers, cumin, oregano, etc. Chile powder is one particular chile, dried and ground, generally labeled with the actual type (ancho, pasilla, etc).

I associate "chilly" and "chilli" mildly with British English, but really I associate them with Indian English which I then tend to assume matches British, since it does a lot of the time.

(Also, I was near but not from the area where "chili" the dish is served as spaghetti sauce, so I also recognize that as chili.)

What is chilli normally served with in the US if not rice?

ReplyDelete(I do sometimes make it with nachos but rice is definitely the norm here!)

On its own, usually. There may be toppings, like cheese, sour cream, green onions, etc., but the chili itself is the main event, eaten like a soup with a spoon.

DeleteAnd it's probably worth noting here that 'eaten like soup' can mean that it's served with saltine crackers. (Crackers and soup don't go together in UK.)

DeleteI've always eaten it with chips (aka French fries) as that is the way I was first served it.

DeleteA friend of mine (from Arkansas) puts a bunch of saltine crackers in his bowl of chili, mixes it up, and calls it "spackle". :) (For non AmE speakers, spackle is quick setting plaster used to patch holes in walls.)

DeleteAlso, most places I've lived (California and the Midwest), chili has beans in it. Texas chili snobs disdain this.

I'm not sure why, but decades ago I was introduced to chili served on rice by a girlfriend (American, despite her last name, which was -- no kidding -- English) who had lived for a while in New Mexico. It's how I prefer it, especially if the chili is spicy, as I like it. I also go for a healthy dollop of sour cream (it cuts the heat too) plus shredded cheddar cheese and chopped red onion on top. Tortilla chips on the side.

DeleteAbout saltine crackers crumbled on a naked bowl of chili: I'm certainly familiar with it. Indeed, once upon a time it seems to me that casual restaurants in the U.S. typically served most soups with a cellophane pair of saltines next to the bowl. Whether they were hastily crumbled on top was one of those ways of distinguishing the state of someone's table manners ... kind of like whether you'd (as the Three Stooges used to do) tuck a cloth napkin into the opening between unbuttoned shirt collar and neck -- instead of placing it in your lap.

By the by, the BrE for 'spackle' is 'polyfilla'.

DeleteAnd can someone if possible translate — or, failing that, describe — saltine crackers?

DeleteI've seen it here (London) served on a baked potato (is that a jacket potato in the USA? Can't remember).

DeleteIt's a jacket potato in UK, not US. (Baked potato in US.)

DeleteThere is no translation for saltine cracker. It's kinda like a salted cream cracker. Kinda. A bit lighter.

Bother, thought I had replied but evidently not. And why am I signed out of Google? Oh dear. Anyway, point is I (BrE) have always called it a baked potato, although obviously I recognise jacket potato as a synonym. A family shibboleth, I suppose?

DeleteI (BrE) have always called it a baked potato as well.

DeleteI wasn’t saying that BrE doesn’t have ‘baked’, but that ‘jacket potato’ is a BrEisn not found in US.

DeleteThinking about it, for me, "jacket potato" is restaurant-menu-speak, like serving one with sour cream instead of butter. At home, I serve baked potatoes with butter (sometimes); in a restaurant I'd expect to be given a jacket potato with sour cream.

DeleteIn my family (Southern NJ, USA), chilli was always served with rice. Always! I was shocked and disappointed the first time I had it without (in a restaurant). Chili needs rice, at least in my head. I just thought that (some) restaurants were weird. Or cheap (I always end up ordering a side dish of rice when it doesn't come with the chilli). And when one of my editors chastised me for bringing chilli and rice to the potluck, I assumed that my way was the norm and blamed his taste on his Texan homeland. Who knew he was the "normal" one?!?

DeleteI also tend to use the double-L spelling, so I guess I'm not really a good source. (I actually had to check the spelling on the fossilised bottle of chili powder in my cupboard to truly accept that we actually use only the one L!)

– AiNJ

In parts of the midwest, chile is served on spaghetti.

DeleteSaltine cracker = soda cracker (don't know if that helps)

DeleteChili can also be served with cornbread in US. Delicious.

Interesting, I hadn't thought about the spelling difference, but it makes perfect sense when it's pointed out.

ReplyDeleteI must admit the thing that made me (Southern UK) double-take was describing chilli con carne as "stew" - it's not a usage that would ever have occurred to me. My understanding of stew is that it has bigger discrete pieces of meat (usually stewing beef) and vegetable, in a thinnish gravy, whereas chilli is made from mince in a thicker sauce. I'm not sure whether that's a universal British understanding, or a more personal one.

Sally, Looks like we were writing about "stew" at the same time. See my comment below. It's also worth noting that while in the US it's probably most common to have minced/ground meat in chili, it's also common to have big chunks of cut-up chuck steak as well (which, I would guess, is the same or very similar to what you call "stewing meat"). See the photos in this recipe: https://www.seriouseats.com/recipes/2011/11/real-texas-chili-con-carne.html. I think I'd be more likely to call this latter "stew" than a version with ground/minced meat for the reasons you describe.

DeleteI know this is aside from the main topic here, but calling chili (con carne) a "stew" struck my American ears very strangely (in that "well, I guess if you think about it, technically it is, but nobody normally things about it that way" way in which a hamburger is technically a sandwich).

ReplyDeleteLanta: Generally speaking, in the United States, chili (con carne) is served in a bowl in its own right and is eaten with a spoon like soup (or, dare I say it, stew). It's often garnished with some combination of cheese, sour cream, diced green onions, diced raw jalapeño. It could be served with crackers or tortilla chips. It can be served as a sauce or topping to other foods (chili dogs, chili fries) but that's not the main, unmarked way it's served. See the first photo at the Wikipedia article for a prototypical example.

Ha! I left my other comment before reading yours and am amused to see that we described chili in almost the same terms, down to the green onions.

DeleteSouthern English here. I always thought that mince is often used for convenience and/or because it's cheape than chunks of beef. Having checked my Delia Smith (imho the definitive cookbook) from 30+ years ago, her recipe uses chuck steak cut into very small pieces.

DeleteFor those asking about my use of 'stew'--it seemed less ambiguous than 'dish', and it's what the OED uses. But I agree, if you said you were serving 'stew', I wouldn't expect chil(l)i.

ReplyDeleteAdding another comment just to get notifications. Blogger has not been notifying blog owners of comments since 25 May, when they said they were working on a fix. But...

ReplyDeleteAh yes, chile with an "e," New Mexico's state vegetable, an altogether different thing. It does indeed go in a stew - green chile stew, which usually also includes some kind of meat, potatoes, onion, and sometimes tomatoes. It's definitely not the same thing as chili con carne. Chile also goes in or on all manner of other foods too, sometimes to the point of ridiculousness (green chile wine, for example), but in most uses it's delicious.

ReplyDeleteI just wanted to add my agreement to the comments above that chile is the pepper (most likely because that's how it is actually spelled in Spanish) and chili is either the dish or the spice that has a blend of chile powder with other stuff. I'm in California and as far as I know this distinction applies in any state with a decent amount of Mexican/other Latino influence.

ReplyDeleteIt's just occurred to me, reading this, that the reason why we expect to eat chilli con carne with rice, is because it's hot. Even though it might originally have come from another part of the world, we think of it as a sort of curry. And that is how we eat curry. Adding some variety of tortilla then corresponds to adding a chapati or a poppadom.

ReplyDeleteThe country is pronounced the same way as chilli but if it wasn't referring to the country, the vowel in 'chile' would be the one in child - as it would be to me if chilli was spelt 'chili'.

I hadn't realised until reading this that chilli powder and the little fiery red chillis derived from a Latin-American plant. I'd somehow imagined they came from the east.

Exactly what I was speculating, @Dru, when I saw the allusion to rice -- in Britain, the closest analog would be to curry, which takes rice, and I'm sure tortillas and tortilla chips were scarce when chili first arrived for y'all.

DeleteOn the ‘erroneous’ marker, is it because capsicums are not actually a form of pepper (i.e. like black pepper)? The pepper-tree, wikipedia tells me, is also botanically not pepper, but it does have similar bundles of little round hard fruits.

ReplyDeleteThat's probably it. I think it'll be removed when they update it, because the meaning of 'pepper' has moved so much.

DeleteThe "erroneous" label on "chili pepper" comes from the OED First Edition, in the entry pepper from 1905, which had a long list of types of pepper: African pepper, anise pepper, bitter pepper, etc. That was carried over unchanged into the Second Edition, but when they revised pepper in 2005, they moved all of those out to sub-entries under the first word, so "chili pepper" is now under chilli, "clove pepper" under clove, etc.

DeleteMany of those other peppers are not botanically in the genus Piper, but they're not marked "erroneous", so that doesn't explain why only "chili pepper" got the label. Maybe they just made a mistake.

Re your comment "it's interesting to see how recent it is to say chil(l)i pepper": the frequency of "chil(l)i pepper" has clearly increased over time (as you can also see in the Google ngram), but it isn't recent; Google Books and Hathitrust find plenty of hits on "chil(l)i pepper" in the 19th century, and even some before 1800. It just wasn't frequent enough back then to get into COHA's corpus.

Lynne, I am surprised that Chili (a town in New York near Rochester) has its name pronounced in the "wifi" manner. (I spent six long years at the University of Rochester as a grad student in philosophy in the 1970s.)

ReplyDeleteAnd on the chili-chile controversy, the Associated Press gives "chili" and "chilies" as the only acceptable forms. Or more precisely, it did in the 2011 edition; I lost access to the online version when I retired.

Ah, I had meant to mention Chili, NY. Thanks! Yes, definitely a Rochester-area shibboleth.

DeleteI was going to ask how one can imagine pronouncing chili as anything other than a short "i". I guess I was proven wrong. "wifi" is pronounced the way it is because it descends from "hi-fi". Of course that doesn't explain why "hi-fi" is pronounced the way it is. When I first encountered it (in print, not spoken) I thought it was in fact pronounced pretty much with the same vowels as "high fidelity" which it is short for. I guess maybe rhyming has something to do with it. Still we've got "Siri" and nobody seems to mispronounce that.

DeleteIt seems words ending with "i" are rare and usually of foreign origin. Still, if I see an unfamiliar word ending with "i", I assume it's a short "i" unless it's clearly a plural or a shortening of another word that has a long "i".

Boris, the sound I perceive inwardly as short i is the stressed vowel of KIT.

DeleteFor me, the first vowel sound of chilli is a KIT sound. But the second vowel is and unstressed happY sound. In some accents these are identical sounds, but not in mine.

The simple reason that few 'native' English words are spelled with a final letter-I is that a very strong convention has virtually always substituted letter-Y.

Boris, I suspect a lot of us would pronounced siri differently if we encountered it exclusively in writing.

DeleteAs you say, the two syllable of hi-fi are pronounced to rhyme (as with wi-fi). Partly this is an echo or high, but it's also a logical spelling pronunciation of stressed syllables in which the vowel letter is not 'checked' by a following consonant letter.

The hyphen underlines the importance of both syllables — leading to both of them carrying stress. Spellings hifi and wifi might invite

a more siri‑like spelling pronunciation.

Upstate and Western New York pronunciations are often unique and baffling. The wifi reference reminded me of Pulaski, NY, which is pronounced Puh-lass-SKY. Of course.

DeleteThis has got me thinking about letter-I and I-sounds in British English. I'm struggling to whittle it down to a short post.

ReplyDeleteMeanwhile, enjoy this rhyming couplet from the folk song The Gallant Frigate Amphitrite

Farewell to Valparaiso, and farewell for a while

Likewise to all your Spanish girls along the coast of Chile

(It actually works when you hear it sung!)

OK, my latest attempt to be brief.

ReplyDeleteScottish excepted, most accents of British English have a set of checked vowel sounds — which can only carry stress when followed by a consonant sound. They are KIT, DRESS, TRAP, LOT STRUT, FOOT and they correspond to historic short vowel sounds.

Accents of American English have a slightly different set (minus LOT), ands both the historical link and the psychological link to short vowels have been severed.

But over here the historical spelling conventions based on historical short~long distinction have a degree of psychological strength. This is particularly true of the default that

• KIT is spelled by letter I followed by two or more consonant letters (or one letter at the end of a word). Exception with another vowel letter such as bury and women are very few.

• PRICE is most often spelled by letter I (or Y) followed by no more than one consonant letter. Even the exceptional spellings usually include the letter I.

The pattern is complicated by spellings that preserve the spellings of words taken from Latin (e.g. finite but infinity) or when suffixes follow a single consonant (e.g. electrician). Another pattern is the alternative long I for words from French (e.g. police, unique) and a few other languages (e.g. casino, ski). And there's the Greek-derived prefix-like phil- and some Greek sword (e.g. epsilon).

We've been faced with two homophones: one an important country with spelling supported by international recognition and the other a foodstuff that was little spoken or written of for much of my lifetime.

The KIT vs PRICE mindset inhibits almost all of us from approximating to a Spanish pronunciation. And even those who try it for the country Chile tend to say CHEE LEIGH.

Besides, we have a third homophone (pertaining to cold wind or water), and we spell it chilly.

This brings out another history-conditioned mindset:— that words do not ent in letter I.

So, we have (in large part) accepted the final letter I in the foodstuff word because it's excusably exotic. But we've remained totally resistant to anything but ill to represent the stressed KIT vowel.

So I'm not surprised that an early generation of Americans associated the spelling Chili with the sound CHIGH LIGH. Just like that folk song I quoted.

This comment was confusing in the font on my font. Glad to see on my PC it has a font that makes the capital I(i) distinct.

DeleteException with another vowel letter such as bury and women are very few.

DeleteSurely "bury" is pronounced with the DRESS vowel, not the KIT vowel? In my dialect of BrE, it is a homophone of "berry".

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteA typo that I failed to spot. The examples I had in mind were busy and women

DeleteBury is a rare case in English where the spelling comes from one Middle English dialect (West Midlands, the ancestor of the standard) and the pronunciation from another (Kentish). Similar things happened to merry and knell, but in those cases the spelling adjusted to fit the pronunciation.

DeleteAs a Scot, I would rhyme bury with furry, which does not rhyme with ferry.

DeleteReading the history of Chili in Spanish, most believe Chili comes from a dish used in the late 1880's in Baja California (Mexico) to extend limited access to meat using chile peppers. It was spread into southwestern US and northern Mexico (probably due to migrant cowboys and farmers across the borders) where the name was anglicized to chili. Chili was introduced to the rest of the US at the World's fair in Chicago by the San Antonio delegation moving the dish from Texmex to an American dish.

ReplyDeleteI'm American and I do enjoy rice in my chili, but I've only had it that way at home by my own doing, I've never ever seen it served that way.

ReplyDeleteThe UK way is *on* rice, not rice in it. :)

DeleteFirst, it's still the same combination. Second, I did NOT say chili in rice. Rice in chili, not chili in rice.

DeleteThat’s what I said ‘rice in it (chili)’. Didn’t mean to offend. Just noting tfst the experience is different.

DeleteUsually, the rice goes round the side of the plate with a dip in the middle into which the meat is ladled. Which confirms my suggestion earlier that we tend to see chilli con carne as a sort of curry, because that is how curry is often served.

DeleteBy the way, in the US does chilli con carne also include red beans? They are more or less obligatory here.

This reminds me. As an American living in Ireland, I've had more than one Irish person tell me they had vegetarian chili con carne for dinner. Which, I understand why this happens (they used chili con carne sauce, and they don't know any Spanish), but it always sounds strange.

ReplyDeleteHow would one say "Chilli without carne"? I frequently make mine vegetarian, it's not a dish (I find) that wants meat.

DeleteAmericans rarely if ever use the full phrase "chili con carne"; we just say "chili." So meatless chili is "vegetarian chili." The full phrase "vegetarian chili con carne" is facially absurd whereas "vegetarian chili" is only absurd is you know what "chili" is originally short for, which I would guess most Americans do not.

DeleteI would just usually just say chili, to be honest. I'm not sure I've ever had regular chili, as I was raised by a vegetarian and am mostly vegetarian myself, so it doesn't really occur to me to clarify. But yeah, vegetarian chili doesn't sound odd to me.

DeleteWhen I worked in a vegetarian cafe in the 1980s (Oxford, UK), we used to serve "chilli sin carne"

DeleteI like it!!

DeleteIn a somewhat similar way, when I described here how in Greece I'd been served a very tasty fish moussaka, a Greek colleague said 'there's no such thing as a fish moussaka; such a thing cannot be', even though everything else about the ingredients and the way it was prepared was the same as a moussaka.

DeleteI frequently cook vegetarian chilli. I'd normally just call it chilli, but I like "chilli sin carne".

DeleteAs I have a young daughter who doesn't like spicy food, I sometimes cook it with no chillies in at all: with lots of paprika instead, and the normal cumin, oregano and garlic, it is still recognisably a chilli. So, if I make a chilli con carne with no chillies and no meat, is it a con?

Paprika is a chile product; dried, ground, and sometimes smoked capsicum berries. So no, Chili with paprika is still chili.

DeleteThe OED treatment of chilli pepper stresses that, botanically speaking, a chilli isn't a pepper. Conversely, the pepper that paprika is made from isn't a chilli.

DeleteI can easily taste the difference — when they're not too hot to disguise the flavour, that is.

In Sweden, a vegetarian chile con carne is called "chile sin carne". And we eat it with rice, of course.

DeleteI'll never forget my first experience of chilli con carne, in Paris in the early 1970s. (I'm British; but there were both British and American people present). It was for a party - the cooks, bless them, didn't realise they needed to taste the liquid, not the meat, and the result was HOT and needed a great deal of rice to "dilute" it... and then someone was vegetarian (rare, in those days, you didn't automatically cater for vegetarians) and ate a plateful of plain rice with every appearance of enjoyment.... How times change - these days I hardly ever put meat in my chilli!

ReplyDeleteBut it was not until 20 years and more later that I discovered that, actually, "chilli peppers" were a category of food, not a food in themselves - in the USA they were called things like chipotle and jalapeno. These days, here, you can get birds eye and Scotch bonnet, but unless it is specified they are still mostly generic "chilli peppers". Oh, and sweet peppers are what we (BrE) call bell peppers.

jalapeno - yes. Or ancho, anaheim, serrano, poblano, and probably a dozen more. These days groceries also have green and red thai peppers (small, thin, hard, and hot). But chipotle is not a separate kind of pepper, it is a pepper that has been dried and smoked.

DeleteIs it? You see, I didn't know that! Okay, we do get more varieties of chilli peppers than we did 20 years ago, but the supermarkets still sell generic "chillis" and anything else is either bought in a shop catering to e.g. Jamaicans or else preserved. Oh, you co sometimes get jalapenos stuffed with cream cheese, and very good they are, too, but they are preserved, not fresh.

DeleteWe call them bell peppers in the U.S. too. Though, I'm never sure if something is a southern thing (where I'm from) or if it applies to America as a whole.

DeleteChili con carne in a Mexican restaurant? But it isn't a Mexican dish! It's Texan or at least Southwestern US. Yes,there are Mexican dishes made of meat and peppers: chile colorado, chile verde, chile de res, but they are not chili con carne. Here in California a Tex-Mex restaurant might have both chili con carne and tacos on the menu but it would almost certainly be advertising itself as Tex-Mex.

DeleteIt's got to be an American thing. I'm from Connecticut and we say bell pepper. In fact, I've only ever heard sweet pepper out of an Englishman's mouth

DeleteYes, I was unclear - I meant that what you call bell peppers are what we call sweet peppers, but I realise that I was ambiguous!

DeleteChili is acknowledged there as a historical spelling,

ReplyDeleteBut not as the earliest. As I read their etymology, the spelling chilli was used in the 16th century to represent the Nahuatl word from which Spanish chili/chile was derived.

The earliest record was in French, so there must have been some motivation to use double-L.

There was indeed a motivation.

DeleteI was beginning to wonder whether the Nahuatl dictionary had been written in French but by a British English speaker..

But no. According Wiktionary the Classical Nahuatl word was pronounced with a long L-sound. They offer two IPA transcriptions. One is tʃ͡iːlli but their preferred one is tʃ͡iːlːi which doesn't suggest a syllabic break between two L-sounds.

About changing the motto of the OED to "The most definitive record of the English language": "most definitive" sounds a little to me like the deviously provocative phrase "more perfect" in the preamble to the U.S. Constitution. Granted, "most" is a superlative and "more" is a comparative ... but both "definitive" and "perfect" in essence convey superlatives, making "most definitive" a pleonasm (not that there's anything wrong with that) and "more perfect" a contradiction that somehow suggests no government can or ever will reach a true state of perfection.

ReplyDeleteWell, 'definitive' has lots of meanings and the slogan is playing on that. Some of those meanings are definitely gradable.

DeleteAnd the sense they're probably most wanting to bring up is 'authoritative', and you can definitely be more or less authoritative--so I don't see a problem here.

We (work colleagues) also came up with 'chili sin carne' years ago when a vegetarian version was served at a party.

ReplyDeleteHas anyone answered the question as to whether the US version includes beans as standard? If it was originally a way of 'stretching' scarce meat, my guess would be yes.

The usual sorts of canned chili are typically found both with and without beans. The version without beans commonly has a very visible note to that effect on the front.

DeleteThat said, I think that if I were to order a bowl of chili (and it's usually sold in bowls or cups) in a restaurant, I'd expect to see beans.

Again, this is for chili, not New Mexico red or green chile, which is an entirely different thing.

There is no definitive answer to the question of "beans in chili", as there are SIGNIFICANT differences in opinion based on where you live. This is similar to the differences in the definition of barbeque across the US (where it can mean anything from an outdoor gathering where food is cooked on a grill to chopped pork in a vinegar sauce to beef ribs cooked in a red sauce). There are as many types of chili (the soup/stew/sauce) as there are regions in the US.

DeleteSo for me, I hate beans in my chili, but I suck it up because I live in a part of the country where beans are required (even if someone is making white chicken chili).

Agree with @Amanda -- you can fill a whole racks of cookbooks just on chili, with wildly disputing recipes. My mother's parents both grew up in the Texas panhandle, so we're pretty firmly of the meat, meat, and more meat school of chili making. Pinto peans are served on the side only (and I've never cared for them that much, but it's been too many years so my tastes may have changed). Oh, and cornbread's pretty much mandatory too, not the sicky-sweet Northern variety with far too much (wheat) flour in them. Preferably in stick form. Wow, typing this makes me remember.....

DeleteMy understanding is that chile, or chili of you prefer, is a lot like barbecue. The recipe varies greatly according to region, and adherents to one variety have very strong opinions as to why their version is the most "authentic". Whete I grew up, chili always had not red beans, but red kidney beans. But I believe that beans in chili is abhorrent to some. From Texas, if I am not mistaken.

DeleteAnother variation in serving, whuch I have not seen mentioned here is "chilimac", which is chili, usually leftover, mixed with elbow macaroni and sometimes cheddar or American cheese. It is often made as a way of stretching the leftover chili.

Another use of dried chillies is to flavour vodka.

ReplyDeleteWe discovered this in a book on 'Russian' cooking (It's actually better known as an Ukrainian recipe) when living in Egypt. It made sense to infuse the local Better than Vodka as imported spirits (or any other imported booze) cost the earth. Lemon zest was probably the best, but juniper berries produced passable gin.

Chilli vodka gives the illusion of greater strength, and other expats copied the idea from us. They also copied from us the Russian way of making a Bloody Mary. This involves floating the vodka over the tomato juice — pouring over a knife, just as you would to float cream on Irish coffee.

This the sort of drink that Russians like. When you knock it back in one — as Russians do — you get a fierce throat attack followed immediately by a soothing draft of tomato juice. The Cairo expats compounded the effect by using chilli vodka.

And they gave the drink a name. They called it a 'Bloody Crosbie'.

My grandmother, way back in the early 1970s or before, used to soak dried chillis in sherry for 3 weeks, before using the resultant liquid to flavour soups and stews. I still do - chilli sherry is very much a thing, and I really like it in cooking. You can top up the sherry a couple of times, too.

DeleteChilli is not the only food spelled with a double letter in the UK and a single letter in the US. There's also pit(t)a and fil(l)et. I wonder if that's coincidence or due to a similar process?

ReplyDeleteI pronounce pitta with the KIT vowel; do Americans pronounce pita with the FLEECE vowel?

There's another food where we do depart from spelling pronunciation of letter-I plus double consonant. At least we do now.

DeleteI'm pretty sure that when pizza was still more of a novelty in Britain, some people pronounced it with a KIT vowel. I don't remember people using an English-type Z-sound. It would have been an easy matter to hear and adopt the extra T-sound. But many British ears were deaf to any other sort of I-sound.

But then pizza became popular and often spoken of, so pretty well everyone uses the FLEECE vowel.

Hi, Rachael -- AmE speaker here, and can attest that I've only ever heard the FLEECE vowel in one-t pita, among AmE speakers.

DeleteAnd in case you haven't seen it before, fil(l)et is discussed here: https://separatedbyacommonlanguage.blogspot.com/2006/08/pronouncing-french-words-and-names.html.

I (BrE) spell it pita and pronounce it peeta. I first came across it over 30 years ago in Australia where some people called it "Lebanese bread"

DeleteThe Italians don't say peetza; it is much more like pitza.

DeleteThe Italians don't say peetza; it is much more like pitza.

DeleteI suppose it depends on how you say KIT and FLEECE in your accent. Personally, I don't think I've ever heard an Italian pronounce any word with the vowel that I use for KIT.

Rachael, the OED etymology of pitta/pita is full of uncertainties and alternatives.

ReplyDeleteThey give the immediate source as Greek πήττα. Letter-by-letter transliteration makes this pitta. However Greek also has the spellings πίτα, πίττα — which transliterate as pita and pitta.

The bread is understood to be an old Jewish Balkan artefact with a name partly influenced by Hebrew. The transliteration — from yet another alphabet — of the Modern Hebrew word is pittāh. But other Balkan languages spell the word with a single letter-T.

My guess is that double letter T (in whatever alphabet) has persisted in various languages even in the absence of a double tt sound. This is what seems to have happened to chilli in French, where doubling a consonant letter doesn't have the effect it has in English spelling.

So, in French the double letter-L is a preservation of a spelling used to transcribe Nahuatl. In British English the spelling is reinforced by its effect of signalling a KIT. In Spanish — and subsequently in America English — they went purely by the sound for the L-sound. In all four cases, the same was involved, since none of the languages/dialects has an independent double ll sound.

The OED gives the US pronunciation of the bread word as /ˈpɪdə/ — that is a KIT vowel and 'flapped' T-sound.

If BrE chilli can be (partly) down to spelling following the etymology, BrE fillet is the result of the opposite.

The French word is filet meaningful 'thread' but also by extension the narrow fleshy band of meat near the ribs, and by further extension to other slices of food from ribs. In English, these feel like two different words — a headband in old poetry, and a cut of meat. I believe the old ribbon-type thing is pronounced only with a KIT vowel. The cut of meat, though, is pronounced not so consistently.

At a restaurant table, it's easy to see filet as a French word and pronounce it with an approximation to French. The OED seems to state that Americans do this all the time with eɪ (sometimes stressed) for the French e (with either KIT or FLEECE for the first syllable). In a butcher's shop, I don't think BrE speakers treat it as a foreign word. I for one would always rhyme it with skillet when talking to a butcher.

Personally, would spell the cut of meat — even outside a restaurant — as filet. But I would spell the verb 'cut from the ribs' as fillet.

The OED spellings from British texts seem to be mostly fillet in the last two hundred years — restaurant contexts excluded.

To summarise

• Neither BrE nor AmE have double consonant sounds (as opposed to the same consonant repeated as in chill longer or fill lately).

• Double consonant spellings in chilli and pitta are based on etymology. But BrE fillet is an invented spelling based on sound.

• BrE is sensitive to the traditional sound-spelling relationship of KIT vowel to double consonant spelling. This created the fillet spelling and reinforced the chilli and pitta spellings.

I am now reminded of an anecdote someone told in a programme on Radio many years ago. He was an Englishman at some sort of banquet in the US and the wait staff were going around the table asking a question. When they got to him, he heard the question as, "How do you like your flaming yonkurt?"

DeleteHe was flummoxed. Was this some item from an exotic cuisine, Turkish perhaps, that he'd never come across before?

Finally, the person sitting next to him translated for him: "How do you like your filet mignon cooked?"

(And, in a similar vein, in 1981 I went with some friends to a Mexican restaurant in Denver and was asked a question that sounded like, "Do you want [some name]s mother?" This was finally explained to me as "Do you want your tacos smothered?" but as I had no previous experience of Mexican cuisine, I was still at a loss as to know what it meant.)

Contrary to the OED, I'd say the usual AmE pronunciation is peeta.

DeleteFWIW, Lynne covered "fillet/filet" and similar words some years ago now, here.

DeletePaul, the last time I said 'Yes' to an incomprehensible offer like that I was in a Leningrad park in winter, queuing at an outdoor beer kiosk. (Draught beer was hard to find in the old USSR.)

DeleteThe vending woman turned to a second tap and gave me a shot of heated foam to take the chill off the glass and the top of the beer — the sipping-from part.

It was good.

Oh, blast, of course there's a better comment further down in the thread, and by the estimable David Crosbie and Lynne herself. Agree with Lynne on AmE pronunciation; I don't ever recall hearing the flap in pita -- just FLEECE plus a fully-enunciated (almost over-enunciated, to AmE ears) T.

DeleteFWIW, I think I only ever hear the FLEECE vowel in pita (the bread word), OED notwithstanding. (AmE, western US)

ReplyDeleteYes, the OED sound file for the entry sounds like a FLEECE vowel. Two editors disagreeing? A typing error?

DeleteUpon reflection, this vowel sound association is strong enough in AmE that it also affects the pronunciation of PITA, the acronym, even though the "I" there stands for "in".

DeleteSorry, Doug, you'll need to explain what PITA stands for, and how it's pronounced.

Delete"Pain in the ass", or "arse" I suppose if you are that way inclined. Using the acronym reduces the chance that your interlocutor will take offense

DeleteTranscription as /ˈpɪdə/ must have been a mistake, which has since been corrected; the OED's page for pita (last modified March 2022) now shows the US pronunciation as /ˈpidə/. (Actually, the t in pita may or may not be flapped and voiced. You can hear both on Youglish. I would say both are normal American pronunciations.)

DeletePITA the acronym stands for Pain In The "Rear End."

ReplyDeleteIn my dialect of AmE, we pronounce both the bread and the name for an annoying person with the FLEECE vowel and a tap in the middle.

Is my family the only one that serves chili with corn bread? Regular unsweetened Southern-style cornbread for everyday, or fancy cornbread with cheese, green chilis, corn, and onions for Superbowl parties.

In most accents of England — and of some other chunks of Britain — the FLEECE vowel makes those words sound like Peter.

DeleteCome to think of it, I have a friend whose unusual name sounds like that even in 'rhotic' accents — accents that pronounce R-sounds even when there's no following vowel. But she's spelled Peta.

Oh yes! The organisation PETA is pronounced the same way — at least whenever I've heard it spoken.

But we do accept the foreign long-I before t in some names taken from other languages: Rita and Margaritaetc, and the more obviously foreign señorita.

I'm fascinating by a distinction: are FLEECE and "foreign-long-I" different is some dialects? To me they're the same: fleece, Lisa, Elise, pizza, Peter, pita, margarita (rocks and salt, please) -- oh, and "please" itself -- all take exactly the same vowel, including length.

Delete(I omitted "Theresa" only because I didn't want to reopen that conversation...) ;-).

DeleteChristian, the historical association of KIT and PRICE with short I and long I respectively has not lost its potency in accents of British English.

DeleteThis can affect our spelling pronunciations — the pronunciation of Lisa to rhyme with miser is still heard. But there's a long-ish history of foreign words spelled with letter-I and a single consonant letter but which are pronounced with something like our FLEECE vowel.

Ignoring exceptions — which is, of course exactly what we do — spelling~sound correspondences fall into three classes:

1. Letter-I followed by two consonant letters (or one final consonannt) corresponds to KIT.

2. Letter-I followed by one consonant corresponds to PRICE.

3. Letter-I followed by one consonant corresponds to FLEECE.

To me at least, both Class 2 and Class 3 are long I. The words covered by Class 3 are foreign and relativelyin origin, so I think of the sound — in relation to its spelling — as foreign long I.

in Accents of English, John Wells identifies three groups of words with the FLEECE vowel. Two had different E-sounds in Middle English, but then merged and changed to the modern sound. English spelling was largely regularised before the two sounds merged, so the former distinction is widely preserved in the spellings ee versus ea. The third, much smaller group is of recent borrowings from French and then other languages. Wells's example list is:

police, machine, prestige, elite, mosquito, casino, trio, ski, chic ...

Of your examples, Peter belongs to the same class as the ee words. And please is, of course, in the ea class. In Middle English the two words were pronounced with different vowels.

I think of both Peter and please as having a long E. But it's impossible to think that of machine. Hence the invented term foreign long I.

But, no, they're not different sounds in my accent or in any accent that I know of.

Leaving aside the word Theresa itself, there are foreign borrowings with E spelling and a FACE vowel, But they're not numerous and don't call out to be treated as a class. Wells lists only

Deletecrêpe, fête (often spelled just crepe, fete), bouquet ...

Also reasonably common: melee, melange

Deleteand if you allow final syllable FACE vowel sound (bouquet) then cafe, duvet, née, parquet, risqué are also reasonably common examples.

Ethan, you've almost persuaded me to invent a new category of foreign long E spelling correspondences. However, John Wells's examples and yours seem to constitute a narrower category — French words with approximations to French pronunciation.

DeleteI wouldn't myself pronounce melange with a FACE vowel, by the way.

OK, I'll renounce my some vows, and attempt a taxonomy on vowel spelling-to-sound correspondences with made-up categories.

DeleteI'll call the categories CHECKED, LONG and INTERNATIONAL.

There's a virtual pure system which doesn't exist even for RP-speakers, but seems to underlie what we actually do.

…..…CHECKED……..…..LONG……....INTERNATIONAL

A……TRAP……………....FACE…….….BATH

E……DRESS……………..FLEECE…….FACE

I…….KIT……………...…...PRICE……….FLEECE

O…...LOT………………….GOAT………..GOAT

U…..STRUT………………Y+GOOSE…..GOOSE

(Y…..KIT………………….PRICE)

Letter, by letter

A:

Between accents of England, BATH words are not consistently pronounced. RP speakers and some others consistently use a PALM vowel. But — depending (often but not always) on geography — many speakers use the TRAP vowel for INTERNATIONAL words. Amazingly, some Pakistanis hear this as an insult.

E:

The INTERNATIONAL correspondence seems to be largely confined to two groups of words:

• obvious French borrowings, some spelled (sometimes) with French accents

• women's names such as Theresa, Irena, Helena...

As discussed elsewhere, there is no consistency over the names.

I:

A long time ago, before American English could even exist, we started taking words from French like police with an INTERNATIONAL vowel correspondence. As already discussed, all dialects use INTERNATIONAL FLEECE for a number of words adopted from a number of languages. But AmE has been readier than BrE to do so with recent borrowings.

O:

American accents have destroyed the system. The LOT vowel is like the PALM vowel, so can't be categorised as distinctively CHECKED. The AmE GOAT vowel is close to the o sound in many languages — in which it can be CHECKED or not. Because there is no vestige of the old SHORT-LONG system, Americans tend to have a GOAT vowel in words ending in –os (see the Barbados thread). This extends to words from Classical Greek where they were spelled with omicron — the short vowel letter.

U:

In LONG correspondence RP and some other accents seem be consistent in inserting a Y-sound in words spelled with U — with the exception of words spelled with –LU- or –RU-. We don't do this with recent and obvious borrowings such as hula or sumo.

In AmE, mesa, beta, eta, zeta, and many other loanwords use that FACE vowel for the e. It's not just French loanwords. There is a variant pronunciation of "rodeo" that uses the FACE vowel as well, but it's not one that I use.

DeleteAnd I'd use the FACE vowel (or a fairly close approximation) for the vowel in melange as well.

My perception is that during the 19th century, AmE was very willing to Americanize pronunciation of loanwords (see the pronunciations of Cairo IL and Versailles IN for examples), but is much less willing to do that now. We seem to prefer a closer approximation of native pronunciation for loan words now, at least for words from languages that Americans commonly borrow from.

Doug, I know of Cairo Illinois only from Blues singers who (to my ear) pronounce it with a FACE vowel. That doesn't seem to me like Amercanising or any other Anglicising. Or is it actually a SQUARE vowel?

DeleteYour pronunciation of mesa is understandable. But beta, eta and theta must reflect a change from the long-E value of the time that your ancestors took to America. Eta itself was the long E of Classical Greek — distinct from the short-E epsilon.

And just how do you pronounces Versailles Indiana?

We too have opened up in the last century or so to pronunciations that run counter to English spelling patterns. Not so long ago, we pronounced Prague to rhyme with vague. And the Irish still do when referring to the Virgin Mary as Our Lady of Prague. But British and Irish alike now use the PALM vowel fro the Czech capital.

But our openness is much weaker than yours — which is somewhat ironic, as we like to pride ourselves on being more open than you to the outside world. Not so, apparently.

David, I think I've mentioned on these threads before that the local inhabitants of Bath pronounce the vowel in their city's name in a different way yet again, neither with the 'trap' vowel, nor the 'palm' one but as a longer version of the 'trap' vowel, a sound which I don't think exists in RP. It's closest to the sound in 'Baa' meant to represent the noise a sheep makes.

DeleteHowever, one also needs to be careful referring to the 'palm' vowel as such. It may surprise people from other dialect communities to be told that there are some dialects where the 'l' in 'palm' represents a sound that is pronounced. It's not the 'l' as in 'light' or 'love' but a sort of swallowed 'l'. I suspect that most of the places where this happens are also rhotic, but not all rhotic places do this.

"Is my family the only one that serves chili with corn bread? Regular unsweetened Southern-style cornbread for everyday, or fancy cornbread with cheese, green chilis, corn, and onions for Superbowl parties."

DeleteNope, as a foreigner transplanted to Southern California, cornbread (fancified or otherwise) is the only accompaniment to bowl of chili I have ever experienced. The chili (con or sin carne) of course has the obligatory diced raw onion and grated cheese topping.

David,

DeleteThe American city of Cairo, Illinois, is pronounced with the FACE vowel. The American pronunciation of the Egyptian city Cairo is with the vowel in PIE (or TIE, DIE, MY, etc.).

In many (most?) American dialects, the FACE vowel and the SQUARE vowel are the same phoneme (what nonlinguists call "long a", so most folks would't really understand your apparent distinguishing of them as different vowels. A coda R does color the vowel, though, so they are different allophones, if that's what you were asking about. In the case of Cairo, Ill., the R is the onset of the second syllable not the coda of the first, so it's a "pure" FACE allophone not the R-colored one. It's pronounced, with an initial K, of course, like "Hey, Row" not like "Hair, Oh." (And the Egyptian city is pronounced like "Tie, Row" not like "Tire, Oh.") Both pronunciations are a little unusual in that the stressed syllable (the first one for both) doesn't pull the R to be a coda as stressed syllables often do.)

Versailles, IN, also has the FACE vowel and is pronounced with the second syllable stressed and exactly like the noun "sales" (as in "Walmart and Target both got back-to-school sales going on right now").

Dru, John Wells's lexical sets were complied to establish a basis in two reference accents: RP and General American. For the most part, vowel sounds in individual accents can be described quite simply in terms of sound values for words in each set. It's simple as long as all the words belong in the usual lexical set. But if someone pronounced a word — the city Bath, say — in a different way to the other words in the set, then it not too difficult to describe it j=in terms of belonging in a different set.

DeleteWhen it comes to local variation such as pronouncing an L-sound in palm say, it's still straightforward to speak in terms of difference from the reference accents.

Wells allowed himself just under two pages to discuss BATH/TRAP/PALM/START vowel sounds in West Country accents. But that's a big geographical area with many local differences. And there are class-based differences too. So there's a lot of detail, but not enough to pin down what he thinks of the accent(s) of Bath (the city).

He does recognise three A-sounds in some middle-class Southampton speakers, for example. At this level of detail he has to use IPA notation

[æː] ~ [æ] ~[ɑː]

hand ~ land ~ command

Sam ~ Spam ~ psalm

But often it's possible to speak of, for example, a lengthened TRAP vowel — a process that can happen in different accents with different actual sounds produced.

PALM was chosen as a label for its lexical set because the 'native' core members are very few indeed — fourteen words, he thought. The spelling of palm (like calm and psalm) is eye-catchingly easy to remember — unlike bra or blah. It's no big deal to explain that in a certain accent the three words spelled with -alm — plus geographical names such as Calne — are pronounced differently from the expected.

Cairo, IL is pronounced with the FACE vowel. Cairo, Egypt is pronounced with the EYE vowel (approximately). Or at least that's the case with all the news presenters and Arabic speakers that I've listened to or talked to. I'd call that an Americanization, though it's possible that was the common pronunciation in all dialects of English at the time the city was established.

DeleteVersailles, IN is pronounced with the FACE vowel and a voiced 'L' (rhyme with "fur sales", though the stress is on the second syllable in 'Versailles').

Those Greek letters are universally pronounced with a European "long-E" (FACE, see, for instance the article "dem" in German, which has a very similar value for the 'e') in AmE.

As to openness, we've been doing mass immigration for quite a long time, so for the average person in the US, direct exposure (non-native-English-speaking neighbors, for instance) to many languages is more common than is my perception of the case in the UK until pretty recently.

Joel

DeleteIn many (most?) American dialects, the FACE vowel and the SQUARE vowel are the same phoneme (what nonlinguists call "long a", so most folks would't really understand your apparent distinguishing of them as different vowels.

That's the beauty of John Wells's LEXICAL SET idea. The notion of a phoneme becomes irrelevant. Only for the purpose of comparing accents, of course. It remains vital in any understanding of a single speaker , accent, dialect, language.

The FACE and SQUARE lexical sets are distinct sets of words, irrespective of whether a speakers perceives them as two phonemes or one. As it happens, the sound values in my near-RP accent sound hugely different, and that's true for most of the accents I'm used to hearing. My ear wasn't attuned to equivalence or near equivalence in American accents. I always understood what you meant, so it didn't jar.

Here in Britain, non-linguists are likely to identify their FACE vowel as long-A — if only because of the way they've been taught to read and spell. My contention is that it remains a psychological reality because in accents of my type the system of the vowel-sound inventory has (in large part) remained unchanged while the values changed dramatically.

The SQUARE lexical set is a Johnny-come lately, the result of a historic R-sound influencing some sort of historic A-sound. In RP (and, I think, in most British accents) it's a stable set of words pronounced with a diphthong which starts like your DRESS vowel or a lengthened 'pure' vowel which starts and stops there. In American accents, I now read, it isn't a very stable set. And it's by no means a distinct one. Outside North America, Wells write, accents (all accents?) make a three-way distinction Mary ~ merry ~ marry.

When I wrote 'Or is it actually a SQUARE vowel?' I wasn't aware how little the idea of a SQUARE lexical set is to North American accents.

So I would say that answer to my question is that the first syllable of Cairo Illinois has a DRESS vowel.

Doug

DeleteCairo, IL is pronounced with the FACE vowel.

In my answer to Joel T Luber, I argued that it's pronounced with a DRESS vowel. This was based on his assertion that the FACE and SQUARE vowels are identical. So let's dismiss this idea and divide our sounds into three sets: DRESS, FACE and SQUARE.

In all the North American accents (except Newfoundland) that John Wells makes inventories for in Accents of English, words in the FACE lexical set are pronounced with a diphthong that is clearly distinct from the vowel shared by words in the DRESS set. He uses the same notation as for British RP — namely eɪ. I agree that this is reasonably close to e in German and other languages. I assume that — unless we were trying to speak German — we could both use a FACE vowel for the town of Bremen.

The SQUARE lexical set doesn't really exist in North American accents, but In British accents it's stable and distinct. Even in the odd accent where the vowel is a longer version of that accent's DRESS vowel, it still sounds to the hearer as clearly distinct. Wells represents the value as ɛə or in some accents ɛː.

Now when 'restored' Classical Greek pronunciation was explained to me, three facts made an impression:

• Eta (Ηη) makes a syllable metrically long.

• In dialects other than Attic the spelling Αα is used instead — again in metrically long syllables.

• The sound that a sheep makes involved the spelling βη- (Attic) or βα- (other dialects).

This was evidence for something like aː or ɑː for long alpha and ɛː for eta.

Now the symbol ɛ represents something with a lower tongue and more open mouth than what is represented by the symbol e. The sound in British accents which is closest to the long version ɛː is the sound we use in SQUARE words. So when we accepted the 'restored pronunciation', that's the value we assigned to eta. To the short epsilon sound we continues to assign the value of the DRESS vowel, which is closer to e in many accents, and in any case is distinctly shorter than and SQUARE sound.

After all, sheep don't go Bay! — any more than they went 'Bee!' before.

Before the reform — in the nineteenth or early twentieth century, depending on the school or university where Greek was being taught — British and American pronunciation would have been identical:

Εε epsilon — DRESS

Ηη eta — FLEECE

Οο omicron — LOT

Ωω omega — GOAT

British schools and universities still use four different sounds

Εε epsilon — DRESS

Ηη eta — SQUARE

Οο omicron — LOT

Ωω omega — GOAT

I get the impression that American schools and colleges use only two.

[Coincidentally, the value of eta in Greek has shifted to something very like the FLEECE value we use in British pronunciation of Classical Greek. This shift had already happened when eta was adapted for the Cyrillic alphabet, where it appears as Ии with a value not unlike our FLEECE.]

Returning to Cairo Illinois. If indeed it is and always has been pronounced with the vowel shares by words such as tape, wait, break, then it looks like a one-off. The nearest spelling similarities I can think of are words like hair, hairy, dairy, fair, fairy, prairie. Are any of those pronounced anywhere with a FACE vowel?

Where I think both colonials and stay-at-homes would have agreed is in assigning the FACE value of the time and place to the spelling ae as in Israel, Ishmael

David,

DeleteI started writing up a big reply about lexical sets vs. phonemes, but I think we're mostly on the same page, just you're more interested in phonetics and I'm more interested in phonology.

Here's my take on the phonemes and allophones for the FACE and SQUARE vowel(s) in General American:

'face'

phoneme: /e/

allophone: [eɪ]

'square'

phonemes: /e/ + /r/

allophone: [eər] or [ɛər]

The last of these is what you're getting at when you talk about the DRESS vowel, right? I agree that the actual pronunciation of "square" in Gen. Am. may have [ɛ], but we don't think of "square" being in the DRESS vowel set because that's not the underlying phoneme. (I can't think of any words with the phonemic DRESS vowel followed by "r," so I wonder if any words that historically had that phoneme cluster merged into the FACE/SQUARE set.)

I did some more digging into the pronunciation of Cairo, Ill., and it seems that locals do pronounce it with the R-colored DRESS vowel allophone (Care-Oh, [kɛr oʊ]) but I've mostly heard it pronounced elsewhere as Kay-Row ([keɪ roʊ]) with the R as onset of the second syllable (as I claimed in my earlier comment). I think both are probably pretty common in various parts of the US. See the discussion here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk%3ACairo,_Illinois#Pronunciation

Here's a video that includes both pronunciations: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuV9_sYmw3U. The narrator uses the Kay-Row pronunciation but all of the interviewees use the Care-Oh pronunciation (see also other videos from this film at http://www.betweentworivers.net/video.htm).

I neglected to finish the story.

DeleteWhen the old pronunciation of eta was abandoned, here in Britain it only affected how we declaimed or cited Classical Greek. The pronunciation of the names of Greek letters remained unchanged. So it's still the FLEECE vowel for the names beta, eta, theta.

But in America the new FACE pronunciation spilled out from the sound of eta to the name of eta — along with beta and theta.

Joel

Delete'square'

phonemes: /e/ + /r/

allophone: [eər] or [ɛər]

The last of these is what you're getting at when you talk about the DRESS vowel, right?

No, Joel. In my accent and many like it /ɛ/, /ei/ and /ɛə/ are three distinct phonemes. The third of these has the two allophones [ɛə] and [ɛəɹ]. However,

• Some broadly similar accents may have [e] where I have [ɛ].

• Some broadly accents may have [ʌɪ] or [æɪ] where I have [ei].

• Some may have [ɛː] and [ɛːɹ] where I have [ɛə] and [ɛəɹ]. Some (the rhotic ones) may have only [ɛːɹ] or [ɛəɹ].

[Clearly, we needn't worry about allophones of /r/.]

What the lexical set concept does is to disregard the phonetic differences that don't matter when comparing accents, and focus on the phonetic and phonemic differences that do matter.

Depending on how you want to look at it, either I have one /ɔː/ phoneme with allophones [ɔː] and [ɔːr] or I have two phomemes: one which is always [ɔː] and the other with allophones [ɔː] and [ɔːr]. Complicated, and unnecessarily so. What lexical sets do is to single out words where my sound corresponds to that of a speaker with a different accent.

• For me FORCE and NORTH are a single set, but that's not true of some other accents.

• In the absence of a following R-sound, my THOUGHT words share the same /ɔː/ phoneme with FORCE and NORTH. This is so obviously not true for yours that there's a widely used term — rhotic — for this difference between accents.

I find it interesting that of the non-rhotic allophones of the vowels in the sets NURSE, NEAR, SQUARE, START, NORTH, FORCE, CURE, two have values that don't exist elsewhere (in at least one accent). These are

• ɜː in NURSE (in many accents)

• ɛ in SQUARE. (in accents with e for DRESS words)

Does that mean that they are extra phonemes in the speaker's inventory? I find it hard to answer, and I don't really care all that much.

So if DRESS, FACE and SQUARE don't refer to phonemes or allophones, what do they signify? They apply to sets of words which share the same sound — whether phonemically distinct or just allophonic — within a given accent.

Some selections from Wells's lists:

DRESS step, edge, bell, threat, many, friend, said, bury

FACE tape, bacon, April, bass (in music), gaol, gage, fête, bouquet, wait, veil, they, weigh, campaign, great

SQUARE care, air, bear, heir, their, prayer, scarce, vary, dairy, aerial (in RP but not in General American)

That last word illustrates how to mark an unusual difference between accents: in mine, aerial belongs in the SQUARE set; in your it belongs in the FACE set. It seems that the same can be said for Cairo Illinois. For the locals, Cairo belongs in the SQUARE set. For outsiders, it belongs in the FACE set.

Joel

DeleteI can't think of any words with the phonemic DRESS vowel followed by "r,"

The DRESS vowel may or may not be 'phonemic' in the sense you're using, but it can certainly be followed by an R-sound. Examples: very, ferry, bury, and many, many more.

Historically, this combination goes back to stressed short-E followed by R followed by a vowel sound. When followed by a consonant, the result was the NURSE vowel.

By contrast, the SQUARE vowel derives from long-A (or diphthong AI) followed by R — as is so often suggested by the spelling.

P.S. Wells doesn't usually write in terms of phonemes, but he does use the concept in this instance. He concludes that the SQUARE vowel is diphthongal and phonemic in RP and in the New York accent — but not in other American accents.

Having grown up less than 50 miles from Cairo, IL, the challenge is that the "ai" has a twist that I can't put in writing. It's a split between Care-oh and Kay-row. Regardless of the actual phonemic spelling, Cairo, IL is pronounced more like Karo Syrup and much less like Cairo, Egypt.

DeleteAlso in Illinois: New Berlin (New BER-lin) and New Athens (New AA-thins), as well as my favorite, Beaucoup creek (buck-up creek)

Reminds me that many years ago I was working on a computer program with a Bulgarian programmer. He had written the spec (in English) and I was asked to review it as it involved some complicated trigonometry that our boss thought Id be able understand.

DeleteI kept on coming across the word "tita" which I didn't recognise so I asked him about it. He was, as is conventional in trig, using Greek letters to denote angles. It seems that theta is pronounced tita in Bulgarian.

Just to confuse things further, I believe the Greeks themselves pronounce both Classical Greek and Biblical Greek (Koine) as though they were Modern Greek. That includes ευ and αυ as ev and av.

DeleteDru, most interesting comment about "Bath" as pronounced by locals. I lived nearby in Wiltshire; Bath was pronounced as you describe. Calne, a nearby town, was pronounced with a short A and the L was sounded, whereas posher people said "Carn". Similarly with psalm, palm, etc..

DeleteAmandaP

DeleteWe also havs a New Berlin in Wisconsin. Pronounced the same as in Illinois. We also have a Rio (Rye-o), and my favorite, Lac Courte Orielles, pronounced LaCooderay.

Paul, your Bulgarian tita reminds me that the letter theta θ was transferred from Greek to the Cyrillic alphabet. So it must have once been used to write Bulgarian.

DeleteI'm not sure what happened in Bulgarian, but in Russian the sound merged with the sound of phi ф. Both letters came to represent the same sound, so theta was only used in words and names taken from Greek. The name Theodor sounded like Feodor in Russian — so that's the way we usually spell Dostoevsky's first name.

Letter fita ѳѲ was dropped from the Russian Cyrillic alphabet after 1917 — which left some Russians with two ways of spelling their surnames. One such was called Ферамин when he was in Russia, but Ѳерамин when he was in America. That's why the musical instrument he invented is sometimes called a feramin and sometimes called a theramin.

As an American, I would never have connected chili, the stew like food, with chili con carne had it not been for this post. We've always just called it chili, whereas I've only seen chili con carne at Mexican restaurants.

ReplyDeleteHow chili is made depends on the region too. People from Texas and Louisiana seem to like to make it without beans and more spicy, and here in Alabama people like beans in it and not quite as spicy. Some people like rice with it but in my family we've never made rice with chili.

I've also never known the difference between the chili and chilli spellings. It seems like one of those grey/gray things where I'd use either one arbitrarily.

I'm an American in my late 20's. I didn't have time to read every single comment. I just have a few remarks:

ReplyDeleteA chili dog is a hot dog with chili on top of it in case any foreigners were confused by the person above who used that term.

We do have chili fries here too. There are some fast food chains here in the South that have those on their menu.

Chili (ham)burgers (hamburgers topped with chili) can be encountered occasionally, especially in the Carolinas.

Chili* can also be put on top of spaghetti in America.

I've never seen anyone put chili on a baked potato here.

* Especially Cincinnati chili, which is really a Balkan Peninsula-inspired ground beef sauce rather than a type of chili. I'm surprised no one has mentioned it yet, but maybe you are all just smart enough to know that it's not really chili, despite its name.

Cincinnati chili was mentioned obliquely ("Midwest") but not by name. I'm from that area but I didn't bring it up because I thought it would confuse the issue of defining actual Chili.

DeleteBTW, chili cheese baked potatoes are on the menu at Wendy's (https://menu.wendys.com/en_US/product/chili-cheese-baked-potato/) and lots of recipes for "baked potato bar" include chili.

UK readers can view a recent Q I

ReplyDeletehere.

I don't think the rest of you can, though.

1. From about 12min 09 sec there's the first 'quite interesting' fact about chilli. When the plant was introduced to Japan in the 1600s, they used to put it in their socks to warm their feet in cold weather.

2. From about 13min 30sec, the second quite interesting fact. Birds can't taste chilli; squirrels can. So bird lovers were encouraged to sprinkle chilli powder on food left out for birds. Unfortunately some squirrels got hooked on chilli and couldn't get enough.

3. From about 14min 29sec, the question

Why might you put chill in a condom?

The answer is not as Sarah Pascoe suggested 'Revenge', but that that some East African farmers use it to ward off elephants from their fields. They tried other ploys but the elephant were too clever. When the farmers attached bells, the elephants silenced them by covering the clappers with their own dung. What does work is to attach a lit firework to a chilli-powder-filled condom and throw it towards the elephant. The chilli explosion drives them off as they have a super-powerful sense of smell and an equally powerful hatred of chilli.

4. From about 25min 16sex, fact four, according to the research of the so-called 'QI elves' is that while Mexicans may eat carne con chili they have no time for chili con carne. One 1959 Mexican dictionary defined it as:

Detestable food passing itself off as Mexican, sold in the US from Texas to New York.

Not everyone in the U.K. uses so-called RP.: perhaps not even most. As I was taught to read, there were basic vowel sounds, exemplified in words such as cat, pet, kit, pot, hut. Then, for each vowel there were alternative sounds, indicated by various spelling conventions.

ReplyDeleteHay, hare, hair

Feet, feat, mete, piece

Nice, light

Boat, more

Foot

I,m sure that there are modifications that I’ve missed. And of course, there are the “yoo” sounds (new, impute, etc.), and the many exceptions that we learned the hard way (police doesn’t rhyme with nice).

In terms of “speaking correctly”, the “length” of a vowel was how long you spent pronouncing it: cat as opposed to caaat. Kate is not inherently longer than cat, but is a different pronunciation of the vowel: I always thought Kate and cat were different values, but the same length, but perhaps I’ve used the wrong terminology.

We were taught that water rhymes with hotter. Pronouncing water to rhyme with patter was incorrect English, but correct Scottish dialect. However, to say waa-uh, I.e. not pronouncing the letter “t”, was regarded as slovenly speech.

And so to FACE and SQUARE. A Scot hears these as the same. We tend to hear the RP version as “skway-uh”. As we were taught, this is lazy speech, as the r in square is as easy to pronounce as the t in water. Likewise, sounding more and moor similarly, to a Scot, is just wrong: the vowel in more is the same as that in boat.

When I was younger, I was often told by Europeans that my pronunciation was easier to understand than that of those using RP. These days, I am often told that I am difficult to understand. This seems to be because, for non-English speakers, the normal English usage has been the one they hear in American television and films. They are a little confused by, but accepting of, what Wikipedia calls the “Mary, marry, merry convergence” in current AmE.

Shy-reply, indeed fewer and fewer people in the UK speak with an RP accent, or even a near-RP accent. But there are similarities that are shared by most of the accents of England, Wales and Ireland.