|

| results of a Google search for "luggage" |

I'm reading Ingrid Paulsen's The emergence of American English as a discursive variety (it's open-access, so you can read it in PDF. But note: it is definitely an academic book). The book is essentially about when American English became "American English". If you subscribe to my newsletter (plug, plug), you'll probably read more about the book at some point in future. Today, I'm just mentioning it because it's inspired me to think more about baggage and luggage. Paulsen searched for this pair of words (among other things!) in 19th-century newspapers in order to find cases of people writing about American versus British English. I wondered if people still perceive a transatlantic difference here.

These words got a boost in the 1800s thanks to the invention of rail travel and the need for a place to put one's stuff on them. Hence the invention, and the naming, of the (AmE) baggage car or (BrE) luggage van, which is one of the contexts Paulsen discusses. It's also been one of my Twitter Differences of the Day:

I can't remember the last time I checked my bags on a train journey, so I haven't run into people calling anything a baggage car or luggage van lately. I have to believe that they were more common in the US (where one could go greater distances by rail/train), since baggage car shows up whole a lot more in American books than either term shows up in British books:

|

| click to embiggen |

But what about the words baggage and luggage themselves? How did they get to be a "difference" and are they still a "difference"?

Let's start with the history. This appears to be one of those differences that came about because English had two words that drifted in different ways in the two places—with more drifting in the UK. The Oxford English Dictionary hasn't fully updated its entries for these words since the dictionary was first published, but we can assume that they got the past fairly correct. Here are the first senses the OED gives for each word:

baggage The collection of property in packages that one takes along with him on a journey; portable property; luggage. (Now rarely used in Great Britain for ordinary ‘luggage’ carried in the hand or taken with one by public conveyance; but the regular term in U.S.) [1885]luggage In early use: What has to be lugged about; inconveniently heavy baggage (obsolete). Also, the baggage of an army. Now, in Great Britain, the ordinary word for: The baggage belonging to a traveller or passenger, esp. by a public conveyance. [1903]

I'd say that the original senses feel "right" for me as an AmE speaker—that luggage is big/heavy enough to be "lugged", but baggage can be more varied. But I am even more likely to use luggage for empty suitcases. I buy new luggage for a trip. A 1997 draft addition to the OED luggage entry says this 'suitcases' meaning dates to the early 20th century.

It only becomes baggage when I fill it up with stuff and give it to someone else to put onto a train or plane. If I handle it myself, I wouldn't call it baggage. I'd call it 'my bags' or 'my suitcases' or 'my stuff'.

I've just asked my English spouse how he'd differentiate the two words:

Him: Baggage sounds old-fashioned, I probably wouldn't use it.

Me: But there's [BrE] baggage reclaim [=AmE baggage claim] at the airport.

Him: That's true...A backpack or a box can be baggage, but it can't be luggage. Luggage has to be cases.

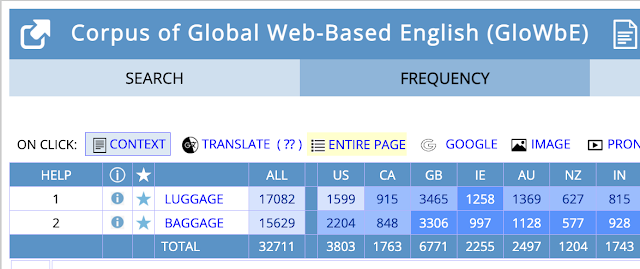

Other than his claim about old-fashionedness, we're pretty much on the same page. And when I look for these things in the GloWbE corpus, they don't show a clear British-versus-American profile: There is more British usage of both terms in that corpus. Maybe this can be attributed to the fact that British people get a lot more (BrE) holiday / (AmE) vacation time than Americans get, so their websites have more discussion of buying/packing/losing luggage or baggage?

|

In books, it looks like AmE & BrE are getting to be more similar in how they use luggage:

So, it doesn't look like the words themselves are good markers of Americanness/Britishness these days. But expressions containing these words can be. We've already seen baggage car/luggage van and baggage (re)claim. There are others.

In BrE, hand luggage is essentially the same as AmE carry-on (bag). Or at least it was. I think the import of carry-on might be influencing its meaning. Spouse says he makes a distinction: you put hand luggage under the seat in front of you, carry-ons in the overhead bin. But, his intuition notwithstanding, shop for hand luggage and you'll be shown carry-ons.

Baggage carousel is marked by the OED (2003) as 'originally and chiefly North American', but it's well used in BrE, as is luggage carousel.

Luggage locker is BrE for the kinds of lockers that one might find in a train station (or also BrE rail[way] station) or (AmE) bus/(BrE) coach station. I think in AmE, we'd just call them lockers.

Left luggage is BrE for the kind of place where you pay someone to keep your bags for you for a while. AmE would call that luggage storage, and you find that expression in BrE too.

Hold luggage (or hold baggage) is BrE for AmE checked bags on a plane. (But checked baggage is found in both.)

Plenty of other luggage/baggage collocations are the same. We all use luggage racks and baggage handlers, and baggage allowance, among other things.

As for metaphorical baggage—emotional baggage and the like, this usage is common to both countries. The OED added a draft definition for it in 2007:

figurative. Beliefs, knowledge, experiences, or habits conceived of as something one carries around; (in later use) esp. characteristics of this type which are considered undesirable or inappropriate in a new situation. Frequently with modifying word, as cultural baggage, emotional baggage, intellectual baggage, etc.

Their first citation for it comes from 1886 in the (London) Times in the phrase intellectual baggage (followed by a US citation in 1922). Cultural baggage shows up in 1967 in Canada, and emotional baggage in 1997 from a UK author. Their first citation for just plain (metaphorical) baggage is from an American author in 1986 (though the OED notes their source as the UK edition of the book).

P.S. If this post interested you, you might also like the post on purses and bags

P.P.S. [22 Sept 2023] Greg [no relation] Murphy sent me this photo, showing Amtrak [AmE] covering all the bases.