Our university's website provides helpful information for students about research and writing. It says things like this:

Another big mistake is to try and write an essay at the last minute.

I look at that and itch to edit it, just like early in my time in England, when my department head sent

round a draft document for our comments, and I "helpfully" changed all the

try and's to

try to's. Imposing your American prescriptions on a learned British linguist is probably not the best idea, and it's one of those little embarrassments that comes back to haunt me in the middle of the sleepless night. I had had no idea that

try and is not the no-no in BrE that it is in edited AmE.

I'm reminded of this for two reasons:

- Marisa Brook and Sali Tagliamonte have a paper in the August issue of American Speech that looks at try and and try to in British and Canadian English (and I've just learned a lot about the history of these collocations from it)

- I've been using this new English usage app and testing it on matters of US/UK disagreement. (Review below.)

The weirdness

Try and is weird. I say that as fact, not judg(e)ment. You can't "want and write an essay" or "attempt and write an essay". The

try and variation seems to be a holdover from an earlier meaning of

try, which meant 'test' or 'examine', still heard in the idiom

to try one's patience. Though the 'test' meaning dropped out, the

and construction hung on and transferred to the 'attempt' meaning of 'try'.

Though some people insist that

try and means something different from

try to, those claims don't stand up to systematic investigation. A 1983 study of British novels by Åge Lind (cited in Brook and Tagliamonte) could find no semantic difference, and a statistical study by

Gries and Stefanowitsch concluded "where semantic differences have been proposed, they are very tenuous". The verbs

be and

do seem to resist

try and and prefer

try to.

There are some cases where

try and doesn't mean the same thing as

try to, where the second verb is a comment on the success (or lack of success) of the trying:

We try and fail to write our essays. ≠ We try to fail to write our essays.

But in most cases, they're equivalent:

Try and help the stranded dolphin. = Try to help the stranded dolphin.

Try and make it up to them. = Try to make it up to them.

(If the rightmost example sounds odd, make sure you're pronouncing it naturally with the

to reduced to 'tuh'. If the leftmost one just sounds bad to you, you may well be North American.)

Though there are other verbs that can be followed by

and+verb, they don't act the same way as

try and. For one thing,

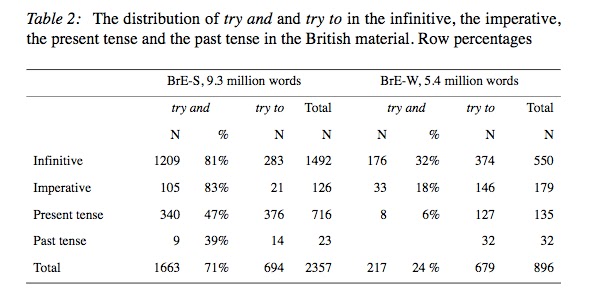

try and seems to stay in that 'base' form without suffixes. It's harder to find examples in the present or past tense (see tables below).

? The student tries and writes an essay.

? The student tried and wrote an essay.

Compare the much more natural past tense of

go and:

The student just went and wrote a whole essay.

So,

try and is a bit on-its-own.

Be sure to/be sure and is the only other thing that seems to have the same grammatical and semantic patterns.

The Britishness

Here's what

Hommerberg and Tottie (2007) found for British Spoken and Written data and for American Spoken and Written.

In the forms that can't have suffixes (infinitive and imperative), BrE speakers say

try and a lot more than

try to. They write

try and less, but in in the infinitive, it's still used about 1/3 of the time.

Brook and Tagliamonte found that BrE speakers under 45 use

try and over

try to at a rate of about 85%, regardless of education level. But for older Brits, there's a difference, with the more educated mostly using

try to.

AmE speakers sometimes say

try and, but they say

try to more. They hardly ever use

try and (where it could be replaced by

try to) in writing.

Brook and Tagliamonte find much the same difference for British English versus Canadian English.

The "non-standard"ness

Though the

try and form goes back before American and British English split up, its greater use in Britain is the innovation here. The

try and form only started to dominate in Britain in the late 19th century.

Brook and Tagliamonte note that it's "curious" that BrE prefers

try and when it has "two ostensible disadvantages":

- it's less syntactically versatile, since it doesn't like suffixation,

- it's long been considered the "non-standard" form, repeatedly criticized in even British style guides.

On the second point,

Eric Partridge's Usage and Abusage (1947) calls it "incorrect" and "an astonishingly frequent error". However, other British style guides are much more forgiving of it. While the third edition of

Fowler's Modern Usage (1996) says that "Arguments continue to rage about the validity of

try and", it notes that the original 1926 edition said that "

try and is an idiom that should not be discountenanced" when it sounds natural. The

Complete Plain Words (1986) lists it in a checklist of phrases to be used with care ("

Try to is to be preferred in serious writing"), but it got no mention in Ernest Gowers' original

Plain Words (1948) or the recent revision of the work by Rebecca Gowers (2014).

Oliver Kamm's rebelliously "non-pedantic" guide (2015) calls

try and "Standard English". Other British sources I've checked have nothing to say about it. Though it's only recently climbed the social ladder, British writers and "authorities" seem, on the whole, (BrE)

not very fussed about it.

American guides do comment on

try and.

Ambrose Bierce (1909) called it "colloquial slovenliness of speech" and

Jan Freeman (2009) calls it "one of the favorite topics of American peevologists". The dictionaries and stylebooks that are less excited about it at least pause to note that it is informal, colloquial, or a "casualism". The

American Heritage Dictionary notes:

To be sure, the usage is associated with informal style and strikes an

inappropriately conversational note in formal writing. In our 2005

survey, just 55 percent of the Usage Panel accepted the construction in

the sentence Why don't you try and see if you can work the problem out for yourselves?

(I can't help but read that

to be sure in an Irish accent, which means

I've been around Englishpeople too long.)

One hypothesis is that

try and came to be preferred in Britain due to

horror aequi: the avoidance of repetition. So, instead of

Try to get to know, you can drop a

to and have

Try and get to know. The colloquialism may have been more and more tolerated because the alternative was aesthetically unpleasing.

Try and is an example I'm discussing (in much less detail) in the book I'm writing because it seems to illustrate a tendency for British English to make judg(e)ments "by ear" where American English often likes to go "by the book". (Please feel free to debate this point or give me more examples in the comments!)

Garner's Modern English Usage

And so, on to the app. The

Garner's Modern English Usage (GMEU) app is the full content of the 4th edition of the book of the same name, with some extra app-y features. I've tested it on an Apple iPod, but I think it's available for other platforms too. On iTunes, it lists at US$24.99.

Full disclosure: Bryan Garner gave me a free copy of this app in its testing stage. I've met Garner in person once, when I'm quite sure he decided I was a hopeless liberal. (The thing about liberals, though, is you can't really be one without lots of hope.) He's a good one to follow on Twitter.

Sad disclosure: I received the offer of the free app not too long after I ordered a hard copy of the 4th edition, which (AmE) set me back £32.99, and, at 1055 pages, takes up a pretty big chunk of valuable by-the-desk bookshelf (AmE) real estate. I bought that book AFTER FORGETTING that just weeks before, hoping to avoid the real-estate incursion, I'd bought the e-book edition for a (orig. AmE) hefty $34.99. So, although I got the app for free, I expect to get my money's worth!!

So far, the app works beautifully, and is so much easier to search than a physical book. Mainly, I've used it for searching for items with AmE/BrE differences. I also used it to argue back to a

Reviewer 2 who was trying to (not

and!) (orig. AmE)

micromanage aspects of my usage that don't seem to have any prescriptions against them (their absence in GMEU was welcome). (Reviewer 2 did like our research, so almost all is forgiven.)

GMEU didn't have everything I looked up (see the post on

lewd), but that's probably because those things are not known usage issues. I had just wondered if they might be. But where I looked up things that differed in BrE and AmE, the differences were always clearly stated. Here is a screenshot of

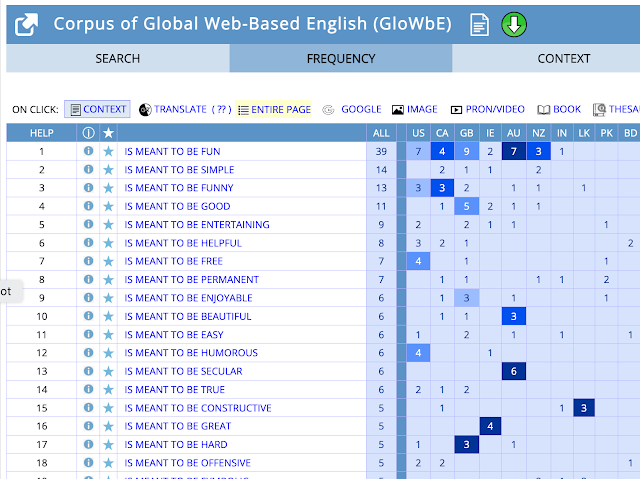

try and:

Garner's book is so big because it's got lots of real examples and useful numbers, as you can see in this example. Nice features of the app, besides easy searchability, include the ability to save entries as 'favorites', tricky quizzes (which tell me I qualify as a "

true snoot"), and all the front matter of the book: prefaces, linguistic glossary, pronunciation guide, and Garner's essays about the language.

The search feature gives only hits for essay topics and entry headwords. That is probably all anyone else needs. I'd like to be able to search, for instance, for all instances of British and BrE to find what he covers. But I guess that's what I can use my ebook for...

Over the course of his editions and his work more generally, Garner has included more and more about British English, but at its heart, GMEU is an American piece of work. Other Englishes don't really (BrE) get a look-in (fact, not criticism). I very much recommend the app for American writers, students, and editors, but also for British editors, who are often called upon to work on American writers' work or to make British work more transatlantically neutral.