Reader Sam* recently wrote to me with the following:

A usage that surprises me every time I hear it is “meant” in the sense of “supposed” or “should be”. For example, in a BBC news item today the correspondent said that there were “meant to be elections this year in Pakistan.” The emphasis seems to be on obligation rather than intention.

[...] do you think this is a recent development, or has British English always had this usage?

In the passive, to be meant has for long had the sense ‘to be destined (by providence), to have special significance’:

When I need you, you are here. You must see how meant it all is—Iris Murdoch, 1974.

During the 20c this use was joined by another passive use in which meant followed by a to-infinitive means little more than ‘supposed, thought, intended’:

For today he was meant to be having dinner with Stephanie at the Dear Friends—A. N. Wilson, 1986.

This altered meaning is now so familiar that its relative newness can cause surprise.

By the third edition (2016), the 'supposed/thought' angle is not even discussed, which seems to indicate that it's no longer seen as a potential usage problem in British English:

In the meaning ‘to intend’, mean can be followed by a to-infinitive (when the speaker intends to do something: I meant to go), by an object+to-infinitive (when the speaker intends someone else to do something: I meant you to go) and, more formally, by a that-clause with should (I meant that you should go). Use of mean for +object+to-infinitive (☒ I meant for you to go) is non-standard.

The Oxford English Dictionary (in an entry revised in 2001) has this sense:

In passive, with infinitive clause: to be reputed, considered, said to be something. Cf. suppose v. 9a.

1878 R. Simpson School of Shakspere I. 34 It is confessed that Hawkins and Cobham were meant to be buccaneers, and it is absurd to deny the like of Stucley.1945 Queen 18 Apr. 17/1 ‘Such and such a play,’ they [my children] will say, ‘is meant to be jolly good.’1972 Listener 9 Mar. 310/1 America..is meant to be a great melting-pot.1989 Times 30 Mar. 15/1 It [sc. evening primrose oil] is also meant to be good for arthritis.

None of these (Oxford-published) sources mark these usages as particularly British, but over in America, Ben Yagoda at his Not One-Off Britishisms blog discussed meant to in 2019 as a British usage that is 'on the radar' in American English.

Mean has many senses that (chiefly AmE) smush (also smoosh) into each other, making it tricky to analy{s/z}e. Take an example like America is meant to be a great melting-pot (that hyphen is very British, by the way). It probably means 'reputed' (i.e. people say it's a melting pot). But it could mean 'intended' (i.e. the Founding Fathers wanted it to be that). Meant in the rest of the 20th-century OED examples can be replaced by reputed, but reputed doesn't seem like the right synonym for the A. N. Wilson example in Fowler's or the Pakistan election example in Sam's email.

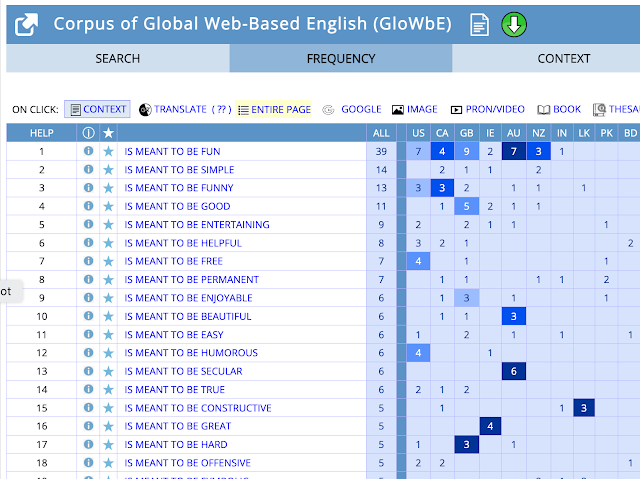

In the GloWbE corpus (data collected in 2012–13), is meant to usually doesn't look very British. For example, here are the results for "is meant to be [adjective]". As you can see (if you click to enlarge), items like is meant to be fun occur at similar rates in American and British. The results are very similar for is meant to be a (as in is meant to be a melting-pot).

Yes, that's just about exactly what I would have said, as a fairly bi-dialectal person. Aside from all of the details and research in your version, of course.

ReplyDeletecomment catcher!

ReplyDeleteI had a devout Presbyterian friend who used to say 'It was meant' = 'God willed it'

ReplyDeleteI agree, and my gut feeling is that even in the sense of "intended," "meant" is used somewhat more frequently in British English than in US English; I don't know whether the statistics bear that out. The use of "meant" to mean something like "expected" reminds me of how "set" is sometimes used in British English: "Pakistan is set to hold elections this year." In American English, "set" would mean something like "completely prepared" in this sentence, but in British English, it can also mean something like "expected" or "intending." (Maybe the "completely prepared" meaning wouldn't even come to mind in a British context; I'm curious about that.) "Set to" is even used for expected future events that weren't planned or intended by anyone in particular: "The demand for steel in construction is set to be slow for the rest of this year" is an example from an online Collins dictionary. Maybe you've covered this use of "set" elsewhere, Lynne?

ReplyDeleteI have heard ‘all set’, meaning completely ready, as in ‘Are you all set?’ , but the longer phrases that you mention seem to be specific to British news services - TV, radio and possibly newspapers, and really only in the past few years. I don’t think I have heard the phrase in colloquial use.

DeleteCouldn't comment earlier, as I was away, although I did read it. Some interesting shades of meaning (sorry!) here:

ReplyDeleteI meant to go to the class (I intended to, but, implied, something happened to prevent it - or I was too lazy, more probably!)

I was meant to go to the class (I was supposed to, but...

I am meant to go to the class (they are expecting me).

There was meant to be a class today....

Is it always negative - something that should have happened but didn't?

To my (US) ears, "meant to" always signals a counterfactual. It was meant to happen, but it didn't (regardless of why it didn't). If the thing happened as intended, you don't have to emphasize the intention. (Not even to mention the apologetic "I didn't mean to"!)

DeleteIt also sounds like a hyper-formal version of "supposed to," and I'm not sure what to do with a vivid memory of Christine in the Love Never Dies musical (basically a trashy fix fic of Phantom of the Opera) saying, about her missing child, "he was meant to be here!" and sounding slightly out of phase with reality, as if there were some unfulfilled destiny there.

It was meant that I should go to the class...

ReplyDeletethat is, I was destined to go there: my joining the class led to something very important (probably positive).

Great post! I've now added 'meant to' to my list of English modal markers.

ReplyDeleteI was puzzled at first because I couldn't see how the initial example, "that there were 'meant to be elections this year in Pakistan'", was an example of "obligation rather than intention". After all, if there was an obligation of elections, if there was supposed to be elections, then someone somewhere had intended for there to be elections. With a dummy subject, there's not any difference in my mind between intent and obligation. Versus "I meant to" (intent) and "I was meant to" (obligation) where there is a difference. But I can see that it's the latter difference that Sam was getting at.

ReplyDelete