Our university's website provides helpful information for students about research and writing. It says things like this:

Another big mistake is to try and write an essay at the last minute.

I look at that and itch to edit it, just like early in my time in England, when my department head sent round a draft document for our comments, and I "helpfully" changed all the try and's to try to's. Imposing your American prescriptions on a learned British linguist is probably not the best idea, and it's one of those little embarrassments that comes back to haunt me in the middle of the sleepless night. I had had no idea that try and is not the no-no in BrE that it is in edited AmE.

I look at that and itch to edit it, just like early in my time in England, when my department head sent round a draft document for our comments, and I "helpfully" changed all the try and's to try to's. Imposing your American prescriptions on a learned British linguist is probably not the best idea, and it's one of those little embarrassments that comes back to haunt me in the middle of the sleepless night. I had had no idea that try and is not the no-no in BrE that it is in edited AmE.I'm reminded of this for two reasons:

- Marisa Brook and Sali Tagliamonte have a paper in the August issue of American Speech that looks at try and and try to in British and Canadian English (and I've just learned a lot about the history of these collocations from it)

- I've been using this new English usage app and testing it on matters of US/UK disagreement. (Review below.)

The weirdness

Try and is weird. I say that as fact, not judg(e)ment. You can't "want and write an essay" or "attempt and write an essay". The try and variation seems to be a holdover from an earlier meaning of try, which meant 'test' or 'examine', still heard in the idiom to try one's patience. Though the 'test' meaning dropped out, the and construction hung on and transferred to the 'attempt' meaning of 'try'.Though some people insist that try and means something different from try to, those claims don't stand up to systematic investigation. A 1983 study of British novels by Åge Lind (cited in Brook and Tagliamonte) could find no semantic difference, and a statistical study by Gries and Stefanowitsch concluded "where semantic differences have been proposed, they are very tenuous". The verbs be and do seem to resist try and and prefer try to.

There are some cases where try and doesn't mean the same thing as try to, where the second verb is a comment on the success (or lack of success) of the trying:

We try and fail to write our essays. ≠ We try to fail to write our essays.But in most cases, they're equivalent:

Try and help the stranded dolphin. = Try to help the stranded dolphin.

Try and make it up to them. = Try to make it up to them.

(If the rightmost example sounds odd, make sure you're pronouncing it naturally with the to reduced to 'tuh'. If the leftmost one just sounds bad to you, you may well be North American.)

Though there are other verbs that can be followed by and+verb, they don't act the same way as try and. For one thing, try and seems to stay in that 'base' form without suffixes. It's harder to find examples in the present or past tense (see tables below).

? The student tries and writes an essay.Compare the much more natural past tense of go and:

? The student tried and wrote an essay.

The student just went and wrote a whole essay.So, try and is a bit on-its-own. Be sure to/be sure and is the only other thing that seems to have the same grammatical and semantic patterns.

The Britishness

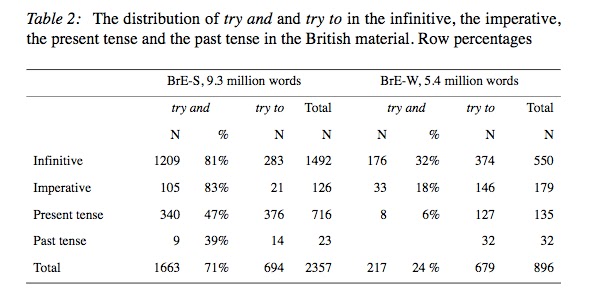

Here's what Hommerberg and Tottie (2007) found for British Spoken and Written data and for American Spoken and Written.In the forms that can't have suffixes (infinitive and imperative), BrE speakers say try and a lot more than try to. They write try and less, but in in the infinitive, it's still used about 1/3 of the time.

Brook and Tagliamonte found that BrE speakers under 45 use try and over try to at a rate of about 85%, regardless of education level. But for older Brits, there's a difference, with the more educated mostly using try to.

AmE speakers sometimes say try and, but they say try to more. They hardly ever use try and (where it could be replaced by try to) in writing.

Brook and Tagliamonte find much the same difference for British English versus Canadian English.

The "non-standard"ness

Though the try and form goes back before American and British English split up, its greater use in Britain is the innovation here. The try and form only started to dominate in Britain in the late 19th century.Brook and Tagliamonte note that it's "curious" that BrE prefers try and when it has "two ostensible disadvantages":

- it's less syntactically versatile, since it doesn't like suffixation,

- it's long been considered the "non-standard" form, repeatedly criticized in even British style guides.

On the second point, Eric Partridge's Usage and Abusage (1947) calls it "incorrect" and "an astonishingly frequent error". However, other British style guides are much more forgiving of it. While the third edition of Fowler's Modern Usage (1996) says that "Arguments continue to rage about the validity of try and", it notes that the original 1926 edition said that "try and is an idiom that should not be discountenanced" when it sounds natural. The Complete Plain Words (1986) lists it in a checklist of phrases to be used with care ("Try to is to be preferred in serious writing"), but it got no mention in Ernest Gowers' original Plain Words (1948) or the recent revision of the work by Rebecca Gowers (2014). Oliver Kamm's rebelliously "non-pedantic" guide (2015) calls try and "Standard English". Other British sources I've checked have nothing to say about it. Though it's only recently climbed the social ladder, British writers and "authorities" seem, on the whole, (BrE) not very fussed about it.

American guides do comment on try and. Ambrose Bierce (1909) called it "colloquial slovenliness of speech" and Jan Freeman (2009) calls it "one of the favorite topics of American peevologists". The dictionaries and stylebooks that are less excited about it at least pause to note that it is informal, colloquial, or a "casualism". The American Heritage Dictionary notes:

To be sure, the usage is associated with informal style and strikes an inappropriately conversational note in formal writing. In our 2005 survey, just 55 percent of the Usage Panel accepted the construction in the sentence Why don't you try and see if you can work the problem out for yourselves?(I can't help but read that to be sure in an Irish accent, which means I've been around Englishpeople too long.)

One hypothesis is that try and came to be preferred in Britain due to horror aequi: the avoidance of repetition. So, instead of Try to get to know, you can drop a to and have Try and get to know. The colloquialism may have been more and more tolerated because the alternative was aesthetically unpleasing.

Try and is an example I'm discussing (in much less detail) in the book I'm writing because it seems to illustrate a tendency for British English to make judg(e)ments "by ear" where American English often likes to go "by the book". (Please feel free to debate this point or give me more examples in the comments!)

Garner's Modern English Usage

And so, on to the app. The Garner's Modern English Usage (GMEU) app is the full content of the 4th edition of the book of the same name, with some extra app-y features. I've tested it on an Apple iPod, but I think it's available for other platforms too. On iTunes, it lists at US$24.99.

Full disclosure: Bryan Garner gave me a free copy of this app in its testing stage. I've met Garner in person once, when I'm quite sure he decided I was a hopeless liberal. (The thing about liberals, though, is you can't really be one without lots of hope.) He's a good one to follow on Twitter.

Sad disclosure: I received the offer of the free app not too long after I ordered a hard copy of the 4th edition, which (AmE) set me back £32.99, and, at 1055 pages, takes up a pretty big chunk of valuable by-the-desk bookshelf (AmE) real estate. I bought that book AFTER FORGETTING that just weeks before, hoping to avoid the real-estate incursion, I'd bought the e-book edition for a (orig. AmE) hefty $34.99. So, although I got the app for free, I expect to get my money's worth!!

So far, the app works beautifully, and is so much easier to search than a physical book. Mainly, I've used it for searching for items with AmE/BrE differences. I also used it to argue back to a Reviewer 2 who was trying to (not and!) (orig. AmE) micromanage aspects of my usage that don't seem to have any prescriptions against them (their absence in GMEU was welcome). (Reviewer 2 did like our research, so almost all is forgiven.)

GMEU didn't have everything I looked up (see the post on lewd), but that's probably because those things are not known usage issues. I had just wondered if they might be. But where I looked up things that differed in BrE and AmE, the differences were always clearly stated. Here is a screenshot of try and:

Garner's book is so big because it's got lots of real examples and useful numbers, as you can see in this example. Nice features of the app, besides easy searchability, include the ability to save entries as 'favorites', tricky quizzes (which tell me I qualify as a "true snoot"), and all the front matter of the book: prefaces, linguistic glossary, pronunciation guide, and Garner's essays about the language.

The search feature gives only hits for essay topics and entry headwords. That is probably all anyone else needs. I'd like to be able to search, for instance, for all instances of British and BrE to find what he covers. But I guess that's what I can use my ebook for...

Over the course of his editions and his work more generally, Garner has included more and more about British English, but at its heart, GMEU is an American piece of work. Other Englishes don't really (BrE) get a look-in (fact, not criticism). I very much recommend the app for American writers, students, and editors, but also for British editors, who are often called upon to work on American writers' work or to make British work more transatlantically neutral.

'Try and...' hurts my ears too! (NZE) It's definitely not standard in written NZE, which uses 'try to', although it crops up in spoken NZE.

ReplyDeleteI am surprised! 'Try and' sounds completely natural to me (NZE as well) while 'try to' sounds more awkward. I would never have known there was an issue without reading these blogs.

DeleteInteresting! I wonder if it's an age thing?? I'm in my 40s.

DeleteI'm English, in my 60s, and on a lot of things a bit of a pedant. I find I use 'try and' frequently and without thinking. I have to remind myself that some other people are picky about it and don't approve. So that would seem to confirm what Lynne has written.

ReplyDelete"... an earlier meaning of try, which meant 'test' or 'examine', still heard in the idiom to try one's patience."

ReplyDeleteAnd also "try for murder, with its noun form, trial, unlikely to fall out of usage any time soon? Also, "try turning it off and back on again".

As for your main point, I feel there is a difference in that try and doesn't have the same expectation of a likelihood of failure. So, "try to keep up" means "it may not be possible for you to keep up, but please make an attempt", while "try and keep up" is, perhaps, more "please keep up, even if that will require a lttle effort on your part".

Only just started reading this thread, so others have almost certainly already written what I am about to, but for me you have hit the nail on the head. "Try and" is encouragement, "Try to" is exhortation. Male, 70+, native speaker of Br.E.

DeleteI was born and bred in a briar patch (well, New Jersey) 58 years ago and live in NYC. I almost always say "try and", and since everything I write (quite a lot, one way and another) is edited only by me, my writing is likewise full of "try and". (What you see here is what you get if you talk to me, pretty closely.) "Try to" has always struck me as pedantic.

ReplyDeleteNothing will persuade me that I personally do not make a distinction between try to and try and.

ReplyDeleteTry and is my unmarked norm. The weird one is try to, which I can use only sparingly for specific meanings, or specific effects.

1. One case has been identified by Zouk. It's when failure is a perceived possibility.

A formal test of this is to combine try with the verb succeed.

Try to succeed is a plausible utterance.

Try and succeed would be odd. It only works as irony or as an accusation that the addressee hasn't been sincere up to now.

Try succeeding is another utterance that can't plausibly mean what it appears to say.

2. Another special context (for me) is when the exhortation implies 'alter your goal'. For that essay-completion advice I could say

Try to have it finished a day in advance

Both of these may carry negative connotations.

1. Zouk's Try to keep up highlight's the addressee's weakness.

2. Try to have it finished by urging a different course of action can be felt as a criticism.

In these and many other utterances try to is (for me) marked for unfriendliness.

I've written here in the past that I believe try and do it takes on the connotations to try doing it. So (for me) there's a friendliness cline

MOST FRIENDLY Try setting yourself an earlier deadline.

MEDIUM FRIENDLY Try and set yourself an earlier deadline.

LEAST FRIENDLY Try to set yourself an earlier deadline.

"MOST FRIENDLY Try setting yourself an earlier deadline.

DeleteMEDIUM FRIENDLY Try and set yourself an earlier deadline.

LEAST FRIENDLY Try to set yourself an earlier deadline."

I think that in my idiolect, the "Try setting ... " version would be the most condescending version. I can only read it in a tone that implies the target would obviously have met the standard if only he had taken the most basic of precautions. It seems to have an unspoken "..., you dimwit!" at the end for me. 8-)

The other two have the typical AmE marking for me (colloquial and not to be used in formal writing for the second on the list and unmarked for the last).

Much would obviously depend on body language, facial expression, and tone of voice of course.

I will mention that if I were to add a "Do ..." to any of the versions and hear them in a British accent (whatever that might mean), they would all come across as exceptionally rude and dismissive.

Yes, Zouk is on the money.

DeleteWhen I started reading the post, I saw it as being mainly an issue of register: in HibE I'd normally say "try and", unless trying to talk proper, and in more formal writing it could easily come out as "endeavour to".

But there are occasions where "try and" is just right, and "try to" would sound hypercorrect and even (dare I say it?) wrong.

I think the try --ing form is not about attempts but "putting to the test" (the other, related, meaning of try). I also agree with Lynne, that the apparent difference in friendliness is connected with a change of register.

DeleteI have to say I couldn't quite put my finger on it, but David's friendliness cline (there's a phrase I'll have to work into casual conversation sometime) pretty much hits the nail I couldn't find on the head. Sorry for the mixed metaphors, I haven't had my first cuppa.

ReplyDeleteI agree with Zouk's risk of failure difference too.

I wonder if we write "Try and..." less because we're writing instructions and minutes a lot more, neither of which are particularly friendly in their syntax. I know there is a big difference in how we speak and how we write anyway, so it could just be that we've go "Try to..." as the written form but I expect to see it as an action point from a meeting, and often be discussed in those terms in the meeting, even a quite convivial one. The formality of the setting and the target setting focus of many meetings makes the less friendly construction work I think?

One white sock, buy him.

ReplyDeleteTwo white socks, try him.

Three white socks, doubt him.

Four white socks, do without him.

I hadn't heard this before, but searching on the internet gave a hit which describes it as "the old adage" which applies to buying a horse. I don't understand the wisdom it purports to enshrine, though. However, this is also clearly a case of putting (the horse, literal or metaphorical)to the test, rather than attempting something

DeleteSome believe(d) that the hoof below the sock is weaker than the other three hooves. It's color is often lighter than hooves without socks, which may be the basis for this.

DeleteHmm.. I think the problem here is, that I'm not at all sure what a horse's "sock" is. I was guessing maybe a section of hair of a different colour above the hoof?

DeleteSorry I spoke!

DeleteThis is probably linked to the British propensity to say "go and do something" where in the US the 'and' is omitted (I'm sure we discussed this about a year ago).

ReplyDeleteI'm not hugely wedded to "try and" but the example given about "try and see" feels most appropriate and I agree with Zouk & David about the possibility of failure: "try and see if you can be nice to your brother at Christmas" seems perfectly fine, whereas a harsher approach would be "try to be nice to your brother". Perhaps the inclusion of the extra verb assists?

That could be the case. To me 'go' followed directly by another verb, as in the very US expression 'go figure' sounds not just odd, but uncouth. It gives the impression that the speaker is deliberately using slang so as to sound cooler than they really are.

DeleteIn my mind "try and" is just one of those things like "Come have a drink with me." It doesn't sound very grammatical, but everyone uses it occasionally, so why not?

ReplyDeleteAs Evan Morris (AmE), the Word Detective, has said, it's a mistake to expect English to be logical. I (AmE) also think that "try to" sounds better, but I think that "try and" is an established idiom.

ReplyDeleteDavid and Eloise: The claim was that there is no semantic distinction. A 'friendliness' distinction is not semantics, but related to formality/register. That we've got here--'try and' is more colloquial, which goes hand in hand with 'friendly'.

ReplyDeleteThe style distinction arises out of the meaning distinction. For example, the exhortation

DeleteHelp the stranded dolphin

says nothing about the ease of doing so or the uncertainty of the outcome.

Try and help the stranded dolphin

introduces the sense of making an effort. Not that the original version didn't imply such an effort, but it didn't make it explicit and salient.

The modification

Try to help the stranded dolphin

introduces a further sense — that a successful outcome can't be taken for granted.

The to-infinitive introduces extra futurity into what is already a future-oriented recommendation. The exhortation is to act in the IMMEDIATE FUTURE to achieve a goal in the SUBSEQUENT FUTURE.

I'm a mid-Atlantic American, and use the two forms interchangeably—though now I wonder if I picked up 'try and' while studying in Britain, or else from my Welsh father. American professors who have noticed me writing 'try and's' have always corrected them—something which annoyed me at the time. Though now it seems ingrained enough that I wouldn't be very likely to use 'try and' in a formal paper.

ReplyDelete'Go and' is another one that seems similar, even if 'go to' isn't an alternate option. It's interesting to think about the different strategies that English speakers use to compound the meanings of verbs—I wonder if the 'and' construction is more centered in Britain as a compounding type of tactic...

Didn't you tackle the Try and/Try to divide in a previous post, Lynne? Seems to me it's deja vu all over again.

ReplyDeleteWanted only to mention that most weekdays I listen to the BBC Newshour between 9 AM and 10 AM on the public radio station here in New York City and feel that I constantly hear Owen Bennett Jones using Try and. Not much doubt in my mind that it is a colloquialism as embedded in British linguistic habit as, say, placing emphasis on the second syllable of the word controversy or pronouncing military as a three-syllable word instead of four.

It's not exactly comparable, but I once got into an argument on the discussion website Quora.com with an anglophone about the value of the phrase in order to -- my view was that it needlessly pads using the simpler and preferable to and his view was that it carries some ineffable gravity my inferior understanding of English had left me incapable of understanding.

Wonder if there was ever a West End production of the long-running American musical The Fantasticks, and if there was, if the producers decided to tweak the lyrics to the song Try to Remember.

Dick

DeleteI don't think all Brits say contro'versy (although I admit I do*). I remember a Monty Python sketch with the scenario of a late-night TV intellectual debate format, called "Controversy". John Cleese was, I think, chairing the panel discussion that was to be, but as he was introducing the programme, one of the participants interrupted him to "correct" his pronunciation of the show's name, whereupon a row on the question broke out amongst the guests. I can't remember (however I try) whether it went to fisticuffs before "something completely different" came on. That must have been late 1960s, early '70s. (Tried to find it on YouTube, but no luck -- too much controversy about Life of Brian). Also, (my old, 1988) Chambers has your preferred pronunciation first.

I feel like I've heard Try to Remember my whole life, but never knew it came from a musical. I think Andy Williams' version was very big here and, of course to is in the title, so it would be hard to mess with. Ironically, the (Californian) Eagles have a song called Try and Love Again, while in his First Cut Is The Deepest, (the English) Cat Stevens promises he'll "try to love again", and Rod Stewart is faithful to the lyrics. Maybe something to do with the expectation of possible failure implicit in the "but..."?

* I'll also own up to "militree" (and "territree" -- though a good friend from the same parts says "terry-tory", for no apparent reason). I wasn't, though, born into such high circumstances as to speak of "med-sin" (for medicine) or "pleece" (for police). If you listen to BBC News, you'll hear more and more American pronunciations coming into use (presumably under the dictate of the Pronunciation Unit). I think defence' disappeared off the airwaves in favour of de'fence maybe mid-1990s. Most irritating! (to old codgers like me).

Or Fy-nance instead of finance, and REE-search instead of research! Both of which irritate me, although the latter rather more than the former.

DeleteAnd while "militree" may be British, what price our respective country's pronunciation of "laboratory" - given all its syllables in BrE, but turned into a homophone of "lavatory" in AmE!

It's strange how several four-syllabled words have changed pronunciation in the last few decades by the stress migrating from the first to the second syllable (in British English; is the same true in the US?). Controversy is one example, lamentable and formidable two more. Clerestory, on the other hand, has gone from having its stress on the second syllable to the first (and become trisyllabic in the process). Why do these shifts occur? I suppose there's a certain logic to lamentable having its stress on the second syllable, as that's where it is lament. On the other hand, that sort of logic: antique, for example, is stressed on the second syllable, but antiquarian is stressed on the third. (Though I saw a reasonably highbrow tv programme recently in which the presenter consistently referred to anTIQUarians.

DeleteI meant 'On the other hand, that sort of logic doesn't always apply'.

DeleteanTIQUarians, by the way, was pronounced anTIKKarans, not anTEEKarans.

Aren't antiquarians an-ti-QUAIR-i-ǝns? I don't think I've ever heard them pronounced any other way.

DeleteThere's some evidence from scansion that 'antique' might in the past have had its stress on the first syllable, not the second, i.e. have been pronounced the same way as 'antic'.

As for 'clerestory', I know one quite often hears clǝ-REST-stǝ-ri, but I'd query whether that has ever actually been correct, rather than attempts to guess it from the spelling? I'm fairly sure it's always supposed to have been pronounced in three syllables as clear-story.

I agree that in 'controversy', 'lamentable' and 'formidable' the stress has shifted from the first to the second syllable. I can remember the previous generation complaining about this back in the sixties.

Shelley's Ozymandias certainly flows better with the antick stress pattern. How recently is the stress thought to have shifted?

DeleteI wasn't familiar with clerestory, but probably would have guessed at clǝ-REST-stǝ-ri in the absence of other information.

Yes, as far as I know 'antiquarian' has always been pronounced with the stress on the third syllable, which was why I was querying anTIKKaran. Is it an uncommon but standard variation, or someone's personal whim? My guess is the latter.

DeleteYesterday on Radio 4 I heard 'rococo' pronounced ROCKerco (instead of the standard ruhCOco). Again, is this 'normal' (perhaps US?) or just one individual's mangling?

The AmE pronunciation I usually notice for rococo is something like "rohcohCOH". (With the usual disclaimers about the difficulty of knowing the sound of one's own dialect, of course.)

DeleteAs an aside, since I speak a rhotic dialect I'm not at all sure how you intend "ROCKerco" to be heard. Is that a voiced "r" or is it intended to modify the sound of the preceding "e"?

Doug

DeleteI'm pretty sure the er stands for a schwa (the little upside-down e in IPA, which not all of us know how to produce on a keyboard*), with the r unpronounced. That's because it's the sound most Brits use at the end of words ending in er, like worker.

On the other hand, I think uh is being used for the same sound in "ruhCOco", and that's probably the way an American might try to approximate it.

I see my old Chambers gives second (as I've always heard), or in the alternative third syllable stress -- but full o (as in roll) vowels throughout (which I've never noticed hearing personally -- always schwa first syllable).

* ǝ Haha! Cut and pasted one from Dru!

Thanks for your replies. I'm a beginner in these matters and I'm enjoying learning. I didn't know how to type a schwa (and I didn't know it's name - great word!), so did my best to come up with a workable alternative.

DeleteProbably too late to post so that anyone will see this, as there are two new threads now, but I've normally heard rǝCohcoh and occasionally roh-coh-COH. I've never heard ROHcǝcoh.

DeleteOn 'antiquarian' I was also (I thought clearly) indicating that I'd never heard the 'qu' pronounced any other way than how 'qu' is normally pronounced. The only words other than French words that are still really French like 'quiche' that offhand I can think of that one sometimes hears as 'k' is 'kestionaire' for 'questionnaire' which, with all due respect to any who pronounce it that way, I regard as a bit of an affectation.

Dick Hartzell, you may be remembering the previous discussion in this post from April 2015 (link): the post was about pleonasms, but comments spent quite a bit of time on "try and" vs. "try to".

DeleteZouk seems to imply that the pronunciation 'pleece' is 'posh'. I think I've only (mostly?) heard it on radio and TV and have always thought it odd, because early 20c writers who used nonstandard spelling to represent uneducated speech used to use 'pleeceman' in this context.

ReplyDeleteActually, on further consideration, I do say "pleece", except when I'm trying to talk proper (ah, the hazards of self-examination). I still think that's also the "posh" pronunciation. Am I wrong?

DeleteYes, I think 'Pleece' is definitely wrong, even though Nick Clegg (a Wykehamist I believe) says it. After all, you wouldn't refer to someone as 'plite', would you? The elision of the syllable is just as much an error as the introduction of the 'u' in 'nuclear', to make 'nuke-u-lar'.

DeleteAnd clear-storey for 'clerestory' is just that - a row of smaller windows above the main body of the nave in a cathedral or other large buildings.

"Pleaseman" appears in Harry Potter, but in that case it's not dialect but rather a character unfamiliar with the word (as wizards have police but don't call them that) sounding it out from memory.

DeleteDick, it would never occur to a BrE producer to alter the lyrics to Try and remember... because it wouldn't mean the same thing.

ReplyDeleteIt's actually rather insulting to be told that what I say doesn't mean what I know it means.

The problem is that the meaning of try and do it isn't always feasible. A more realistic exhortation may be to try to do do it. But we urge the less feasible thing.

Returning to Lynne's examples

Try and help the stranded dolphin.

Try and make it up to them.

These are not radically different from

Help the stranded dolphin.

Make it up to them.

In many contexts they would be equally appropriate things to say. However, there may be contexts in which the addressee don't obviously have the strength or resources or moral authority or time to do thin thing without choosing to make an effort.

That's what they mean

'Make and effort and help the stranded dolphin.'

'Make an effort and make it up to them.'

Now it may not be feasible to do the thing despite one's efforts. What does exhorter do? He or she can simply take it as read — so obvious as to need no comment, and therefore irrelevant. This is what I and many BrE speakers do. Or they can acknowledge the possibility of failure by urging the addressee to make an attempt.

Try to help the stranded dolphin.

Try to make it up to them.

OK, so far a simple dialect preference. But BrE speakers — and producers of musicals — do recognise contexts where feasibility is a consideration. The point about the song is the last line of each verse

Try to remember and if you remember

Then follow

The singer acknowledges that the hearer(s) may not remember.

It would be strange for me to say

?Try and help the stranded dolphin, then tell me whether you've succeeded

?Try and make it up to them and if you manage it let me know

PS

I remember that earlier thread and tried a search but couldn't find it.

hi all

ReplyDeleteyou may be interested in playing with a motion chart (you need flash enabled browser) of verbs following try to, try and from Corpus Of Historical American English COHA http://media.englishup.me/tryTO_tryAND.html

ta

mura

Mura Neva

DeleteI don't understand your(?) motion chart. The x-axis is apparently labelled both by date and as TRY_AND, while the y-axis is labelled TRY_TO. I tick one verb in the scrollable list and press play and then see a number of blobs of different colour in a vertical column over the beginning of the x-axis. The column moves to the right, while the balls change colour and position in the column. What is this telling me?

In the distant past I never noticed the difference, and I've always been used to hearing both, in both the US and UK. (Parents from Nebraska, I was raised in the Pacific Northwest and have lived in Britain for over a decade.) I think 'try and' has a more colloquial sound, which is why it persists in conversation, but it doesn't sound wrong to me. The implication is virtually the same as 'try to' except less specific. 'Try and' implies 'make an effort and do this' rather than 'attempt this specific thing'. I suppose you could say it's similar to 'Pull your socks up and find a job'.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete"I think defence' disappeared off the airwaves in favour of de'fence maybe mid-1990s. Most irritating! (to old codgers like me)."

ReplyDeleteHuh. de'fense (or de'fence) isn't exactly an Americanism. It's used primarily with reference to sports -- (The Giants have a strong de'fense), for example. But in other contexts the stress changers. It's always (Department of Defense'), for instance. Or (the defense' rests).

Hmm. That's interesting. I'll have to listen out for particular usages. Perhaps I haven't noticed the usual pronunciation in BBC broadcasts, just the one I regarded as American, which would have stood out.

DeleteWhy the difference for sports, anyway? In fact, I can't think of a British sport where we use the term defen{c/s}e, though I don't follow sport much, so other Brits here might be able to. When I played football (soccer) as a youth, we just had forwards and backs, which latter were either full- or half-. Same in rugby, with the addition of three-quarter-backs. Please don't ask about cricket.

@Mrs Redboots

ReplyDelete... what price our respective country's pronunciation of "laboratory" - given all its syllables in BrE, but turned into a homophone of "lavatory" in AmE!

But what price our respective countries' pronunciation of "lavatory" - given all its syllables in AmE, but compressed to three syllables in BrE!

I still haven't got over my initial resentment at two assertions:

ReplyDelete1. that try and and try to are synonymous

2. that try and is weird

The natural reaction to [1] is to assert a meaning for try and which is consistently distinct from that of try and. I think that would be pushing it too far. Even in my speech there are contexts in which the two are interchangeable. But then, as I said to Dick, there are contexts in which a construction without try is equally interchangeable.

The examples I centred on were:

Save the stranded dolphin.

Try and save the stranded dolphin.

try to save the stranded dolphin.

Make it up to them.

Try and make it up to them.

Try to make it up to them.

Both examples involve IMPERATIVES — one use of the bare citation form of a verb. Which leads me to my answer to [2], or one of the two alleged signs of weirdness: the incompatibility of try and with any verbal suffix.

So when do we use the bare citation form?

IMPERATIVE

Try and help ...

Try and make it up ...

BARE INFINITIVE

I should try and help the stranded dolphin.

I should try and makeit up to them.

TO INFINITIVE

I want to try and help the stranded dolphin.

I want to try and makeit up to them.

OVERT SUBJUNCTIVE

I insist that he try and help the stranded dolphin.

I insist that he try and make it up to them.

But what of the remaining MOOD? I actually have some difficulty with

INDICATIVE

?Whenever that happens, we try and help the stranded dolphin.

?Whenever that happens, we try and makeit up to them.

Now that I write these sentences down, I find that I'm less unhappy than I expected. Nevertheless, I still feel them to be marginally less natural than the sentences with other MOODS.

What the NON-INDICATIVE MOODS have in common meaning-wise is some sense of open-endedness — the event represented by the verb is contemplated rather than asserted.

Other suffixed forms involve NON-FINITE verb forms which also lack the sense of open-endedness.

trying and saving stranded dolphin

(having) tried and saved the stranded dolphin

These both speak t me of accomplishment

The second alleged sign of weirdness is that style guides consider try to as

• wrong

or

• if not irredeemably wrong, at least inappropriate in formal writing.

To the first i would answer that The thing that you'r liable to read on Strunk an White, they ain't necessarily so.

To the second, there are all manner of forms that are best used informally — but without being considered weird.

Do, or do not. There is no "try and do".

ReplyDeleteEppure si move.

DeleteI will, however, grant you that there's no try and don't.

OK, let me get it out of my system.

ReplyDeleteTake Zouk's example Try and keep up vs Try to keep up.

What makes this a good example is that IMPERATIVE sentences more than any other show a consistent difference in the speech of at least some BrE speakers.

There are — at least — two ways in which IMPERATIVES are used in utterances

1. The speaker assumes that

• the addressee is capable of performing instruction

• he/she the speaker is entitled to issue the instruction

Utterances of this kind include orders, demands, regulations, commands ...

2. The speaker makes neither of those assumptions.

Utterances of this kind include urging, recommending, requesting, pleading, encouraging ...

So Keep up can be

• a Type 1 utterance if spoken by, for example, a coach or sports teacher

• a Type 2 utterance if spoken by, for example, a fellow runner or an encouraging parent

Try to keep up is similarly flexible.

• as a Type 1 utterance the coach/teacher browbeats the runner

—— to accept his/her authority

—— to believe himself/herself capable of keeping up

• as a Type 2 utterance the fellow runner/parent delivers the words in such a way as to convey

—— warm concern for the runner's best interest

—— belief that success is not impossible (though not assured either)

Let's forget about Type 1 utterances for now. And lets take urging as the most telling example of Type 2. In my speech I can use a range of sentences for urging including the following:

SENTENCE.........................LITERALLY

Keep up...............................'I instruct you to keep up.'

Try to see up.........................'I instruct you to try.'

Try keeping up......................'See what happens when you keep up.'

Try and keep up ...................'See what happens when you try.'

Thus even for me Try to keep up and Try and keep up often amount to the same thing in this Type 2 urging sense. But the literal distinction is available, and may become salient. When challenged to detect a difference in meaning I find that difference obvious. Of the four possible sentences Try and keep up is by far the most appropriate.

[Try keeping up is the least appropriate, but that's another story.]

American here, and if I can't just say "try" on its own, I almost always use "try to" - except in cases like the one shown in your GMEU screenshot ("...use the fear to try to panic..."). If "to" precedes the "try", I am very unlikely to use it again. The repetitiveness makes it sound awkward.

ReplyDeleteI'm surprised no one mentioned this; it's the first thing I thought of as a possible justification.

Jane, we Brits need no justification. We are comfortable with 'try and' wherever you would use 'try to'. We are also comfortable with 'try to', but use 'try and' more often.

ReplyDeleteOne comment split into two because of length.

ReplyDeleteEven though I have a sensitive BrE ear, I seldom notice whether speakers say 'try to' or 'try and', and I suspect that anyone choosing one over the other aiming to convey a subtle difference in meaning will find that subtlety lost on me, unless spoken with reinforcing emphasis. I doubt that I am alone in this. I also think that most of the above analysis is post hoc rationalisation rather than introspected description of actual thought processes or analyses of existing writing. I reject any subtle difference that could exist because (a) in speech, emphasis will massively outweigh any potential subtlety in meaning and (b) in writing, AmE editors can happily change all the 'and's to 'to's, apparently without degradation of meaning. I am firmly of the opinion that this is merely a case of different usage rather than different meanings, an opinion that has become firmer after reading all the comments above.

However, I am intrigued by the sentence with the 55% AmE acceptability rate, "Why don't you try and see if you can work the problem out for yourselves?", with its three verbs 'try', 'see', 'work out'. This is different from other examples because of the third verb and the resulting compound conditional nature of 'see if you can work it out', which is unlike the simple verbs in Lynne's other examples: 'write', 'help', 'make it up to'. There are potentially three uncertainties: trying could succeed or fail (to find out whether they can solve the problem); 'see if' could turn out positive or negative (they find out whether they are able or unable to solve the problem); and a 'Yes I can' answer could still lead to a correct or incorrect solution to the problem. 'Try and see if' may be such an outlier that my analysis is wasted, but I am intrigued by it, so here goes.

The sentence, which is surely spoken rather than written, varies in meaning for me depending on whether "TRY AND SEE" is spoken as a unit or as "TRY, and SEE". In the former, "try and see" to me means something like "test and thereby discover" (the other meaning of try), while the latter clearly means "make an effort, and thereby discover".

Part two.

ReplyDeleteFor those who prefer "Why don't you try TO see", when it is spoken as a unit "TRY TO SEE" is weird. Not "Why don't you try to [= attempt to] / see if [= discover whether] you can work out the problem", but the two combined: "Why don't you attempt to discover whether you can work out the problem". At best I suppose this could mean something like 'Can you find an approach that you might apply in attempting the solution?', but indubitably the example sentence is not how one would phrase that suggestion. (I know this looks like I'm trying to apply logic to language, which is pointless (eg "'Try and' excludes the possibility of failure"; not to a Brit it doesn't), but unless one of those verbs is redundant they must have a combined meaning that is different from either of their stand-alone meanings.)

Considering TO with the alternative emphasis, "Why don't you TRY, to see" logically means "Why don't you attempt [to solve the problem], in order to discover whether you can", and "Why don't you TRY, and see" logically means "Why don't you attempt [to solve the problem], and you will discover whether you can", but in reality the meaning is identical and the choice between them would be governed by whatever the speaker feels more comfortable using, rather than a deliberate decision based on subtle potential differences in meaning.

The real problem with this sentence is the inclusion of "see if", which seems to take it outside the realm that this blog post addresses. Without the "see if", "Why don't you try TO work the problem out" is fine AmE and logically fine and for Brits would probably pass unnoticed, while "Why don't you try AND work the problem out" would probably be preferred in BrE although logically suspect (so what?) and (judging from the comments) would be unexceptional to many AmE speakers.

The adverbial adjunct "to be sure", meaning "certainly", is not specific to Ireland; I don't recall hearing it here any more than in the rest of the anglosphere; here as elsewhere it is formal and occurs mainly in writing.

ReplyDeleteSo how, then, did "to be sure" become one of the catchphrases of the stage Irishman? I surmise, by conflation of two genuine Hibernicisms:

1. discourse marker "sure", meaning "don't you realise; as anybody should know"

2. "to be sure to be sure", meaning "[in order] to make doubly sure" (not meaning "certainly") I can't say to what extent #2 feeds off ironic knowledge of the stage-Irishism; it is somewhat informal but not jocular.

mollymooly

DeleteIn the OED entry for surely there are marginal cross-references to

be sure to

be sure, to

The former I've already quoted. (It should appear below here.) The latter includes a comment of which you'll disapprove

In affirmative use now often associated with Irish English.

The quotes up to Bunyan are in written style, but from Swift onwards they nearly all seem to be conversational. They quote several English-of-England authors, but a recent quote is from a work called May Lord in His Mercy be Kind to Belfast: It's a fine afternoon now to be sure isn't it?

I thought I remembered another Irish literary but conversational use and sure enough (? to be sure) I found it:

Buck Mulligan thought, puzzled:

— Shakespeare? he said. I seem to know the name.

A flying sunny smile rayed on his loose features.

— To be sure, he said, remembering brightly. The chap that writes like Synge.

I disapprove of the spurious association with Irish English, but the OED is quite correct to state that such an association is often made.

DeleteThe quote from Ulysses is intentionally stage-Irish.

The Belfast quote is from a taxi driver: "And how are you then today sir? It's a fine afternoon now to be sure isn't it? It's been like this all day here from first thing this morning, so it has. Over from the mainland are you sir? Did you have a good flight? On business or pleasure are you? And is this your first visit to us now, or have you been in the Province before? How long'll you be staying with us then? Well sure that'll be long enough for you to get a good idea of the place so it will."

There are some pan-Irish features and some specific to Northern Ireland I don't hear down south, all laid on thick in the manner taxi drivers the world over are wont to adopt for impressing tourists with local colour.

Best Belfast quote I heard was while waiting in a queue for car-hire at Aldergrove - I beg its pardon, Belfast International - Airport. "Could you just be leaving me a wee telephone number, now?"

DeleteAn Edinburgh equivalent is Will you take a wee seat.

DeleteI went to the OED to look up to be sure — and found an entry much more relevant to this thread

ReplyDeleteand

10. Connecting two verbs, the second of which is logically dependent on the first, esp. where the first verb is come, go, send , or try. Cf. COME v. 4c, GO v. 30c, SEND v.1 8b, TRY v. 16b. Cf also SURE adj., adv., and int . Phrases 7a. Now .colloq and regional.

Except when the first is come or go the verbs in this construction are normally only in the infinitive or imperative.

[OE West Saxon Gospels: Matt . (Corpus Cambr.) viii. 21 Drihten, alyfe me ærest to farenne & bebyrigean [c1200 Hatton to farene to beberienne] minne fæder.]

c1325 (▸a1250) Harrowing of Hell (Harl.) 152 Welcome, louerd, mote þou be, þat þou wolt vs come & se.

1526 Bible (Tyndale) Mark i. f. xliijv, Whos shue latchett I am not worthy to stoupe doune and vnlose.

1599 in Edinb. B. Rec . 250 [The council] ordanis the thesaure to trye and speik with Jhonn Kyle.

1671 MILTON Paradise Regain'd i. 224 At least to try, and teach the erring Soul.

1710 SWIFT Jrnl. to Stella 12 Oct. (1948) I. 53 But I'll mind and confine myself to the accidents of the day.

1780 MRS THRALE. Let. 10 June (1788) II. 150 Do go to his house, and thank him.

1811 J. AUSTEN Sense & Sensibility III. xi. 238 They will soon be back again, and then they'd be sure and call here.

1878 W. S. JEVONS Polit. Econ . 42 If every trade were thus to try and keep all other people away.

1887 T. HARDY Woodlanders I. viii. 153 Promising to send and let her know as soon as her mind was made up.

1925 F. S. FITZGERALD Great Gatsby ii. 33 Here's your money. Go and buy ten more dogs with it.

1959 F. O'CONNOR Let. 20 Nov. in Habit of Being (1980) 359, I have been wanting to write and thank you for sending back the manuscript.

1985 J. KELMAN Chancer (1987) 250 The safety helmet's really important, aye, mind and get yourself one.

2004 A. SILEIKA Woman in Bronze 309 He invited Josephine to come and see the plaster.

Note especially the 1599 quote.

The inclusion of the Milton quote despite the comma after try seems to imply that the lexicographers disagree with the punctuation. That is to say, they don't think Milton meant 'try the erring soul and teach it'.

The cross-reference in that entry for and is to

ReplyDeletetry

16 b. Followed by and and a coordinate verb (instead of to with inf.) expressing the action attempted. colloq. Cf. AND conj.1 10.

1686 J. S. Hist. Monastical Convent. 9 They try and express their love to God by their thankfulness to him.

1802 H. MARTIN Helen of Glenross II. 143 Frances retired, to try and procure a little rest.

1819 MOORE in Notes & Queries (1854) 1st Ser. 9 76/1 Went to the theatre to try and get a dress.

1855 in COLERIDGE Mem. Keble (1869) II. 425, I have something to write to you on that matter, which I shall try and put on another piece of paper.

1878 W. S. JEVONS Polit. Econ. 42 If every trade were thus to try and keep all other people away.

1883 L. OLIPHANT Altiora Peto I. 251 He had good reason to think that Sark was likely to try and back out.

"try and see" is fine because it's not the same as "try to see." "Try TO see" means you may or may not be able to physically see (ex. "Try to see over the fence.") "Try AND see" means try it and find out the results.

ReplyDeleteWhile looking for something else, I discovered that the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English has a sub-section devoted to Try + to +verb v. try + and + verb. The descriptive paragraph is interesting enough and short enpough to quote in full.

ReplyDeleteQUOTE

There is an additional alternative with infinitives which is found only with the controllin verb try: try + and + verb. This pattern alternates with the standard pattern of try + to + verb.

He'll probably try and wrestle it away from me. (CONV)

cf. He'll probably try to wrestle it away from me.

One has to try and find out what has happened. (FICT)

cf. One has to try to find out what has happened.

This discourse choice is not available when the verb try occurs with inflections such as -ing or -ed:

She was trying to prove a point. (FICT †)

cf. *She was trying and proving a point.

Do you remember when we tried to make fluffy dogs?

cf. *Do you remember when we tried and made fluffy dogs?

UNQUOTE

The labels CONV and FICT indicate that sentences are from large corpuses of CONVERSATION and FICTION written and spoken texts. The † symbol indicates that the quotation has been shortened. The * symbol indicates that the sentence is ungrammatical.

In the next paragraph they report the statistics.

Of try + and + verb they find

• It is very rare in the corpuses for NEWS and ACADEMIC registers — less than ten times per million words.

Nearly all occurrences are to + try + and + verb — thus avoiding an infinitive within an infinitive.

* In CONVERSATION it is much more frequent — 80 times per million words, compared with 200 times per million words for try + to + verb.

45% are of the pattern to + try + and +verb.

* In the FICTION corpus it occurs c20 times per million words in BrE bit c2 per million inAmE.

They conclude with a DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

QUOTE

Overall, try + to +verb must be considered the usual unmarked choice. Try + and + verb is a colloquial structure that is relatively common in conversation, but generally avoided in formal written registers. When used in fiction, it typically appears in the dialogue of fictional characters:

Conversation:

Well we did try and mend it several times. (CONV)

Can you try and keep still. (CONV)

I'm going to try and get the three o'clock train. (CONV)

Fiction:

I'll try and come tomorrow. (FICT)

just think of that, and try and get that into your head. (FICT)

Nearly all occurrences of try + and + verb in news and academic prose are used to avoid a sequence of to-clauses:

He had practiced putting on his kitchen floor at home to try and prepare himself for the greens. (NEWS)

It follows that any teacher persuaded to adopt the innovation must be willing and able to explore modifications to his repertoire in order to try and achieve the hoped-for improvement in his pupils' understanding. (ACAD †)

UNQUOTE

J.R.R. Tolkien was a famous defender of "try and". He wrote in a letter about the copy-editing of The Lord of the Rings, "Jarrold's appear to have a highly educated pedant as a chief proof-reader, and they started correcting my English without reference to me: elfin for elven; farther for further; try to say for try and say and so on. I was put to the trouble of proving to him his own ignorance, as well as rebuking his impertinence."

ReplyDeleteAs this editor points out, "try and" is used in The Lord of the Rings only in dialogue, and only by hobbits (except once by Aragorn in conversation with Frodo, and once in narration from Sam's point of view). The hobbits also use "try to", so if anyone wants to analyze the text to see if there's a semantic difference, go for it!

Tolkien also used "try and" quite a lot in his letters, including another famous quote: "[C.S. Lewis] said to me one day: 'Tollers, there is too little of what we really like in stories. I am afraid we shall have to try and write some ourselves.'" He used it occasionally in his critical essays, too.