I've mentioned making and taking decisions before (15 years ago!), in the context of writing about light verbs. That was back in the days of shorter blog posts. The post began with a reader query:

Can you tell me why some people make decisions and others take them?

And I said (emphasis added):

The reason, of course, is that some people speak some dialects and other people speak other dialects. AmE speakers generally make decisions and BrE speakers can also take decisions.

Make and take in these contexts are light verbs. Light verb is defined by the Lexicon of Linguistics as "thematically incomplete verb which only in combination with a predicative complement qualifies as a predicate". In other languages, this usually means a fairly semantically-empty verb that occurs with another verb in a sort of compound-verb (Japanese and Korean have lots of these). In English, the term usually refers to verbs that add very little to the sentence but occur with nouns (usually) that have been derived from verbs. So, in this example's case, one could decide with a regular old verb, or make/take a decision with a light verb plus a nominali{s/z}ation of the verb decide: decision.

Because I'm thinking about the language of decision-making elsewhere in my life, I had a deeper look into how much decision-taking happens. The key thing to notice is that taking a decision is not the most comon way to say it in BrE. While BrE speakers (in 2012, when this data's from) write take a decision at six times the rate that AmE speakers do, they write make a decision at nearly 18 times the rate that they say take.

In popular discussions of language, there's a tendency for people to perceive phrases that one group says and the other doesn't as the British way versus the American way. But English gives us lots of ways to say lots of things, and the number of ways that one group has doesn't have to be the same number of ways as another group has. That's the case here. British has more light verb variation with the word decision than AmE has.

There's another (not unrelated) tendency in popular transatlantic language discussions to assume that if BrE is using the same form as AmE when it has another form available, then they must be using the "more American" form because of "Americani{s/z}ation". Is that what's happening here?

Here's make/take a decision in Hansard, the record of the UK parliament (where lots of decisions happen!) over 210 years. You can see that people didn't use these constructions much before the 20th century, and at the start (before 1940), there is some preference for take. But the numbers and the differences are small. Because the amount of data for each decade is uneven, one needs to look at the colo(u)rs when comparing across years. The darker the blue, the more 'of that time' the phrasing is. There are two things to notice about this:

- There's been more make than take since the 1930s.

- In 'the most take' decades (1960s onward), take is playing second fiddle to make.

- If there's AmE influence, it's happening well before mass media.

- There might be a different pattern emerging for making a decision versus taking the decision. Maybe taking feels more definite than making. After all, things come into existence through making. We take things that are already known to exist.

As for the history of AmE, it's a pretty solidly make place, with just a bit of take in the 1940s—and then a spark of it in the 2010s. Nascent British influence? Looking at US occurrences of it in his Not One-Off Britishisms blog, Ben Yagoda calls it 'a novelty'.

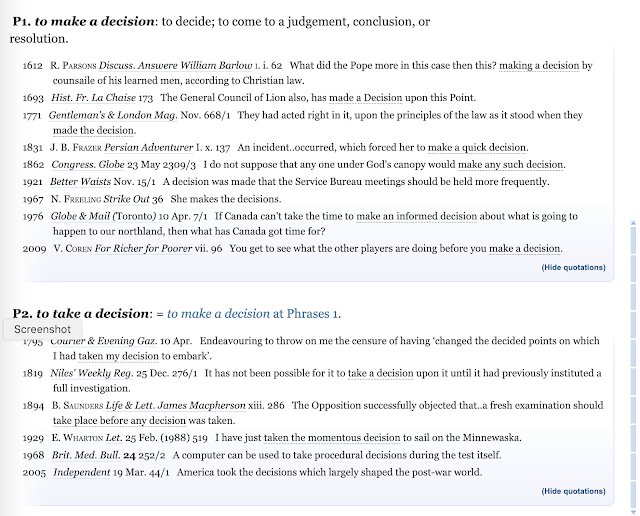

Going a bit deeper into the history, the OED tells us that make a decision has been around (in England) since the early 1600s, and take a decision shows up (in London) in the late 1700s, in a period where the US and UK aren't talking to each other much. This helps explain why make is more present in all of the time periods in both places and why take has no roots in AmE.

So there's what I've been looking at recently!