It was a tough year for deciding on Separated by a Common Language Words of the Year, and so I am very grateful to those who nominated US-to-UK and UK-to-US borrowings that seemed 'very 2018'. So grateful that I offered a prize for the best nominations. And our first winner is: Simon K! Simon—please contact me off-blog with your postal details and your choice of prize: Lane Greene's Talk on the Wild Side or my The Prodigal Tongue.

And Simon's winning word? Well, some of you are going to complain that it's not a word. Enjoy your complaining. I've written several times about why 'that's not a word, that's a phrase' complaints don't bother me. If you want to read several paragraphs on the topic, see this old Word of the Year post. To give you a taste of it, I'll quote myself:

I've noticed it too—from Jeremy-Corbyn-supporting Facebook friends sharing links from dodgy websites because of their distrust of the "MSM". Among my US Facebook connections (who are politically more varied than my UK ones), I see MSM used by people on the left, but more from those on the right. But that sample is very biased.

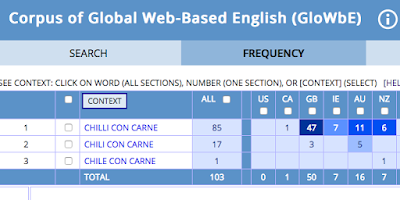

The term isn't in a lot of dictionaries, and it's not in the ones that I check that have date-of-origin information. There are examples of mainstream media in the Corpus of Historical American English going back to the 1980s, but it really picks up in the 2000s decade in the US. In the News on the Web corpus, it's present in the UK since 2010 (when the corpus starts), but doubles in usage in 2016 and continues to rise in 2017. For some reason, the stats don't show up for all of 2018 data on that site, so I won't say it's absolutely of 2018, but it seems to continue to spread this year.

Mainstream media is used in a purely descriptive way by lots of people for a lot of reasons. I note that Ben Zimmer was given an award (well deserved!) for his "linguistic contributions to mainstream media." It's the abbreviated form MSM that often takes on a pejorative tone—and very often a pejorative tone is taken toward its pejorative tone. A lot of examples in the NOW corpus from 2018 are like this one (by a conservative columnist), identifying MSM-use as a symptom of 'nuttiness':

Looking at the latest near-London* uses of MSM on Twitter, one can find more sincere usages. It's not surprising that many instances of it are in discussions of Brexit—seemingly from both sides of the issue. But as in my Facebook feed, a lot of UK uses seem to relate to Jeremy Corbyn (and whether he gets a fair deal from the MSM). In the Google Image Search I did to find the illustration for this piece, the two key "victims" of MSM media bias are Corbyn and Stephen Christopher Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson).

So, established in the US for a while before coming to the UK, but in very active use in the UK now...that fits my criteria for a WotY. Thanks again, Simon!

Oh, and speaking of Words of the Year and the authors of the two book prizes for this competition, Lane Greene, Anton La Guardia and I talked about words of the year for Economist Radio (released this week, but recorded before I'd decided on my WotYs). Please listen here!

*Sorry to be London-centric, but when I tried putting 'UK' in Twitter Advanced Search, it gave me zero results!

And Simon's winning word? Well, some of you are going to complain that it's not a word. Enjoy your complaining. I've written several times about why 'that's not a word, that's a phrase' complaints don't bother me. If you want to read several paragraphs on the topic, see this old Word of the Year post. To give you a taste of it, I'll quote myself:

It all comes down to your definition of word. We can fight about it, but I'll just phone in my part of the fight because 'word' is not a terribly useful linguistic concept. Most people think of words as bits of writing with spaces on either side, but that doesn't work [because it's circular reasoning...]. [This Word of the Year is] a bit of language whose meaning is more than the sum of its parts and whose form-meaning association has to be learn{ed/t} by, and stored in the memory of competent speakers of the language. That's good enough for me.And so what is it? It is...

Mainstream Media (or MSM)

Here's what Simon said in his nomination:

You could make a plausible argument that that I'm a year late in nominating this, but I'd make a couple of points.

Firstly, I think that the usage has changed over this year. In 2017, it was still being discussed as though it's notable that the term was being used here - see, for example, this article, the media talking about the media. By 2018, the term is being used much less self-consciously, in contexts such as sport - see this, from the footballer Stan Collymore.

Secondly, with all the caveats about its use as a source, I notice that the Wikipedia article on "Mainstream media" had no UK section until 2018.

I've noticed it too—from Jeremy-Corbyn-supporting Facebook friends sharing links from dodgy websites because of their distrust of the "MSM". Among my US Facebook connections (who are politically more varied than my UK ones), I see MSM used by people on the left, but more from those on the right. But that sample is very biased.

|

| Image from https://www.adfontesmedia.com/ |

Mainstream media is used in a purely descriptive way by lots of people for a lot of reasons. I note that Ben Zimmer was given an award (well deserved!) for his "linguistic contributions to mainstream media." It's the abbreviated form MSM that often takes on a pejorative tone—and very often a pejorative tone is taken toward its pejorative tone. A lot of examples in the NOW corpus from 2018 are like this one (by a conservative columnist), identifying MSM-use as a symptom of 'nuttiness':

"The Westminster bubble” is a phrase so universal that it is in danger of losing its meaning – or, worse, becoming a sign of slight nuttiness, along with phrases like “wake up, sheeple”, “the MSM”, and “I’m a Liberal Democrat”.Of course, the NOW corpus is mostly made up of mainstream media sources, so one would expect them to be pejorative about the pejoration (though it does include the comments sections—and many of the examples seem to be from angry commenters). There's a problem in counting how many MSMs there are in BrE, as it's also used a lot in public-health talk about Men who have Sex with Men—but the frequency of MSM overall doubled about the same time that mainstream media doubled.

Looking at the latest near-London* uses of MSM on Twitter, one can find more sincere usages. It's not surprising that many instances of it are in discussions of Brexit—seemingly from both sides of the issue. But as in my Facebook feed, a lot of UK uses seem to relate to Jeremy Corbyn (and whether he gets a fair deal from the MSM). In the Google Image Search I did to find the illustration for this piece, the two key "victims" of MSM media bias are Corbyn and Stephen Christopher Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson).

So, established in the US for a while before coming to the UK, but in very active use in the UK now...that fits my criteria for a WotY. Thanks again, Simon!

Oh, and speaking of Words of the Year and the authors of the two book prizes for this competition, Lane Greene, Anton La Guardia and I talked about words of the year for Economist Radio (released this week, but recorded before I'd decided on my WotYs). Please listen here!

*Sorry to be London-centric, but when I tried putting 'UK' in Twitter Advanced Search, it gave me zero results!