Knickerbocker in English starts out in the US, where it was used to refer to descendants of the early Dutch colonists in Manhattan, formerly New Amsterdam. Knickerbocker (in various spellings) was a common name among those settlers, but the one that inspired the New Yorker nickname was the fictional Diedrich Knickerbocker, the supposed author of Washington Irving's satirical A History of New York (1809). It seems to get going as a term for such New Yorkers in the mid-19th century. Irving and some writer contemporaries later became known as the Knickerbocker Group.

But the more famous group of people named after the knickerbocker nickname is the basketball team, the New York Knickerbockers, which these days tends to go by the shortened name, The Knicks.

Baggy trousers

|

| See Fashion History Timeline for more |

This fashion sense of knickerbockers moved over to the UK too. In the US, it is often shortened to knickers (it's a clipping), but not BrE because...

Women's undies*

After knickers came into BrE, it started to refer to women's underpants. The AmE panties can be given as an equivalent, except that many AmE speakers (including me) find the word panties a bit (AmE) icky, and so we just say underwear. Technically, underwear can refer to more than just those small bottom pieces, but if I say "I need to do laundry. I'm out of underwear", it's specifically those bottoms that I'm talking about. (Bre) knickers is not so icky in its natural environs.

Though knickers is a very clear example of a Britishism now, it's interesting to note its AmE roots, since it is a clipping of knickerbockers. I presume this is because women's undies used to look like knickerbocker breeches. Such undergarments were also called bloomers (in both Englishes), as were the outerwear women's knickerbockers that gained popularity as women started bicycling. (Unrelatedly, bloomer also happens to be the name of a type of bread loaf in BrE.) In BrE, the word knickers changed with the changes in underwear styles, but the word bloomers didn't.

I've written about knickers a couple of times before: in contrast to men's (BrE) pants and in expressions like red shoes, no knickers.

*Undies appears to be originally BrE (early 20th c), but has long been well-established in AmE too.

Ice cream

This whole post got started because an English friend gave the word knickerbocker as an example of a word with three Ks (in discussion of this tweet) with the aside "as in knickerbocker glory", leading me to think that he only really knew the word in that context.

A (BrE) knickerbocker glory is an ice cream sundae served in a tall glass. The first citation for it in the OED is in a Graham Greene novel in 1936—though the term was clearly well-known at that point since he didn't have to explain it. It only takes off in British books in the 1970s, though, when my friend and our friends were growing up, eating ice cream.

This is quite a while after Americans invented the word sundae, which was originally Sunday, as in the day of the week when it was (purportedly) served. About this, the OED says:

Evidence suggests that the use of Sunday

to designate an ice-cream dish of this kind originates with Chester C.

Platt (1869–1934), proprietor of Platt and Colt's Pharmacy in Ithaca,

New York, who is said to have served it to Unitarian pastor John M.

Scott at his premises after the Sunday church service on 3 April 1892. A

letter from a patent attorney dated 24 March 1894 shows that Platt

sought advice on trademark protection for the use of ‘Sunday’ for

ice-cream novelties a few days earlier. The motivation for the subsequent respelling of the word [...]

is uncertain: it may reflect an attempt by other retailers to avoid a

perceived breach of trademark; it may be a reaction to the religious

associations of Sunday as a day of abstinence; or it may simply have

been intended to be eye-catching.

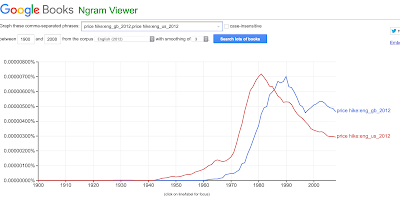

The knickerbocker glory is a prototypical ice cream sundae, but the word sundae has not caught on so much in BrE as in AmE: