Hello from the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Linguistics of English, or #ISLE5, as all the cool kids are tweeting it. We have an afternoon for touristic activities, but since we're in London, I'm feeling a combination of (orig AmE) 'been there, done that' and 'I could do that any time'. What's not available any time is a bit of quiet to blog. So, yay for everyone else going to Samuel Johnson's House (been there, got the postcards) and for my lovely hotel lounge and wifi. Today's post was started possibly years ago (I've lost track), when Lauren Ackerman asked me about British chilli versus American chili.

Hello from the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Linguistics of English, or #ISLE5, as all the cool kids are tweeting it. We have an afternoon for touristic activities, but since we're in London, I'm feeling a combination of (orig AmE) 'been there, done that' and 'I could do that any time'. What's not available any time is a bit of quiet to blog. So, yay for everyone else going to Samuel Johnson's House (been there, got the postcards) and for my lovely hotel lounge and wifi. Today's post was started possibly years ago (I've lost track), when Lauren Ackerman asked me about British chilli versus American chili.I went to my usual first stop: the Oxford English Dictionary. And I am sad to say that the entry for this item has not been fully updated since the first edition in 1889—which is to say, look at those spellings! (Not blaming them, just sad for my post that they haven't got(ten) to this one yet!)

Yes, chilli is still the BrE spelling for piquant peppers—but giving chilly as the alternative spelling and not the standard AmE chili reads very odd in the 21st century. Chili is acknowledged there as a historical spelling, and is present in the quotation evidence in the entry. And it's consistently been the more common spelling in the US:

|

| (click to enlarge) |

At the conference, I've been at two sessions where someone's called into question the OED tagline, visible at the top of the dictionary screenshot: 'The definitive record of the English language". That's marketing talk, not lexicographical talk, and it's unfortunate. There can be no definitive record of the English language, because there is no definitive English language. It's always varying and changing and you can never know if you've found the first instance of a word or the last one, etc. So here's a little plea (in the form of advice) to the Oxford University Press: If you put most before definitive it would be an accurate tagline. And it would have a marketing-department-friendly superlative in it! Win-win!

As a side-note, there's this little bit of puzzling prescriptivism in the run-on to the entry (i.e. the additional defined items at the end), which seems to have been added later—or at least I'm assuming so, given the AmE spelling (it's hard to tell, though, the link to the previous edition includes none of the run-ons).

I've been trying to figure out what that 'erron.' is referring to. I believe what it's saying is that the "real" meaning of chili pepper is 'pepper tree' and it's an error to use it to refer to chil(l)is, but why does it only have the US spelling? It's not clear to me when this chili pepper was added to the entry, as the link to the 2nd edition does not include all the compounds that are in the run-on entries. But it must be old, as it's not marked as a post-2nd-edition addition. But it's interesting to see how recent it is to say "chil(l)i pepper":

Anyhow, back to the word itself: it comes ultimately from Nahuatl, with an /l/ sound in the middle. We pronounce it with a 'short i' sound (like in chill). You can see, then why BrE likes the double-L spelling: without a double consonant, it looks like it should have a a different vowel: we say wifi differently than we'd say wiffi; fury versus furry, etc.

So why does AmE have a single L? My educated guess would be because Americans have had more consistent contact with Spanish. When the Spanish went to spell it, they used a single L, because double consonants don't do the same thing in Spanish spelling that they do in English. If you pronounce chilli in Spanish, there's no L sound. (What sound is there depends on your dialect of Spanish, but I learned in my US Spanish classes to pronounce the LL like a 'y' sound.) It stayed Spanish-ish in American, while getting a more English-ish spelling in Britain.

Now, I think that back in the mists of time when Lauren requested a post on chil(l)i, she meant the stew, rather than the fruit. I am not going to wade into the debates about what "real" chil(l)i (con carne) should have. But I will say this: every American I've seen to order the dish in the UK has had a moment of "Whaaaa?" when it was served with rice. Not something we're used to. But nice when you get used to it.

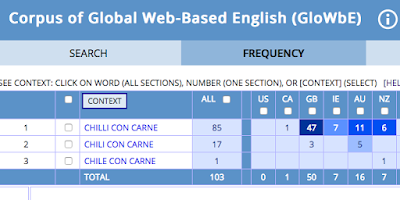

There is another spelling issue here, though. The pepper almost always ends with an i, but the stew sometimes ends with an e. But not much anymore, according to my corpus searches:

And on that note, I'll post this before my battery dies!