For part 1 of the 2019 Words of the Year, click here. Now we're on to the US-to-UK WotY.

I had pretty much decided not to do a US-to-UK Word of the Year for 2019. The words nominated were generally ones that had made a big splash in English recently on both sides of the Atlantic, rather than long-standing Americanisms that were making a splash in Britain. I had begun to think that BrE had reached peak Americanism. But then I went through my top tweets of the year, and saw one that made me think: "Oh yeah, that's it."

The US-to-UK Word of the Year is:

Here's the tweet that reminded me:

Now, this choice might be controversial in that gotten is not just and not originally American. It is one of those linguistic things that mostly died in the UK while it thrived in the US. When I moved to the UK, a colleague told me that you'd still hear gotten among old people in Yorkshire. I haven't had the chance to bother any old people in Yorkshire about that, but -en forms of get were found far and wide in English dialects. That said, the OED has it as "chiefly U.S." and it is widely perceived in the UK as an Americanism. In England you do hear it more from Americans (in the media, if not in person) than from British folk. Here's a bit of what I said about it in The Prodigal Tongue:

That part of the book goes on to examine the evidence that gotten only really got going in the US—that it was not used much in the formal English of those who came from England to the Americas, and that its use exploded only in the late 19th century, when the US was finding a voice of its own. (Want to know more? I have a book to sell you!)

So, while gotten is not just American nor originally American, America is where gotten made its fortune. The "standard" British participle for get is have got, as discussed (along with its meaning) in this old post.

What's interesting about gotten in Britain in 2019 is that it's been used quite a bit in places where you don't tend to hear non-standard, regional grammatical forms: like on the BBC and in Parliament. And I have heard it among my child's middle-class (orig. AmE) tween friends here in the southeast. Here are some interesting examples, besides our friend Radzi.*

On the CBeebies (BBC channel for young children) website:

In a BBC news story about an orange seagull in Buckinghamshire:

In the linguistically (and otherwise) conservative Telegraph newspaper:**

By then-Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry, who got into trouble for saying:

And in the House of Commons:

The other examples above (and indeed Radzi's uses that inspired my original tweet) are have gotten just as a plain old verb in its many meanings. Those interest me more because they do seem more like the re-introduction of the get-got-gotten paradigm, and not just certain constructions that have been remembered with a certain verb form.

A lot of the British gotten that I've been exposed to is from homegrown children's television and children, and that's what really seals it for me as a 2019 word. After 20 years of not hearing it much (and training myself out of saying it much), I'm really noticing it. You can find lots of people, particularly older people, in the UK talking about its ugliness or wrongness, but the fact that younger people are un-self-consciously saying it makes me think that it will get bigger still.

And on that note, a bit later than is decent, I say goodbye to 2019!

Footnotes:

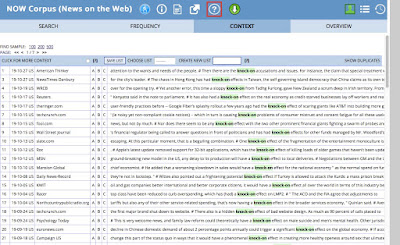

* I haven't presented corpus numbers in this post, since the bulk of the gotten numbers in corpora tend to be (in news) quoted Americans or (in other things) in set phrases. The Hansard corpus tool at Huddersfield University doesn't seem to be able to separate the gottens from the ill-gottens—which is a form that has remained in BrE despite the more general loss of gotten.

** (I got quite a few google hits for gotten in the Telegraph, for which I could see the gotten in the preview. But for some, when I clicked through, the same sentence had got. Might this be because some stories were originally posted with gotten then changed when the "error" was caught?)

|

| Radzi Chinyanganya, WotY inspiration |

The US-to-UK Word of the Year is:

gotten

Here's the tweet that reminded me:

I'll admit getting teary over @iamradzi's departure from Blue Peter, but the reason (for a linguist) to watch his 'best of' episode is the number of times he says 'gotten'. It really is making a comeback in UK. If we can resurrect a verb paradigm, imagine what else we can do 😉— Lynne Murphy (@lynneguist) April 30, 2019

Now, this choice might be controversial in that gotten is not just and not originally American. It is one of those linguistic things that mostly died in the UK while it thrived in the US. When I moved to the UK, a colleague told me that you'd still hear gotten among old people in Yorkshire. I haven't had the chance to bother any old people in Yorkshire about that, but -en forms of get were found far and wide in English dialects. That said, the OED has it as "chiefly U.S." and it is widely perceived in the UK as an Americanism. In England you do hear it more from Americans (in the media, if not in person) than from British folk. Here's a bit of what I said about it in The Prodigal Tongue:

That part of the book goes on to examine the evidence that gotten only really got going in the US—that it was not used much in the formal English of those who came from England to the Americas, and that its use exploded only in the late 19th century, when the US was finding a voice of its own. (Want to know more? I have a book to sell you!)

So, while gotten is not just American nor originally American, America is where gotten made its fortune. The "standard" British participle for get is have got, as discussed (along with its meaning) in this old post.

What's interesting about gotten in Britain in 2019 is that it's been used quite a bit in places where you don't tend to hear non-standard, regional grammatical forms: like on the BBC and in Parliament. And I have heard it among my child's middle-class (orig. AmE) tween friends here in the southeast. Here are some interesting examples, besides our friend Radzi.*

On the CBeebies (BBC channel for young children) website:

In a BBC news story about an orange seagull in Buckinghamshire:

Hospital staff said the bird "had somehow gotten himself covered in curry or turmeric".

In the linguistically (and otherwise) conservative Telegraph newspaper:**

Yet, it is the ageing filter that has gotten most people talking.

By then-Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry, who got into trouble for saying:

The Lib Dems have gotten kind of Taliban, haven’t they?

And in the House of Commons:

- "I would like to share some of the thoughts of organisations that have gotten in touch in recent days to share their experience of training mental health first aiders..." —Luciana Berger, 17 Jan 2019

- "...those in Sinn Féin say, 'Well, we’ve gotten away with two years of saying we’re not going back into government until...'" —Gregory Campbell, 5 Mar 2019

- "...the mess that this place has gotten itself into..." —Deirdre Brock 19 Mar 2019

- "...the best way of dealing with this is not through a voluntary levy based on the least that can be gotten away with" —Jim Shannon, 2 July 2019

The other examples above (and indeed Radzi's uses that inspired my original tweet) are have gotten just as a plain old verb in its many meanings. Those interest me more because they do seem more like the re-introduction of the get-got-gotten paradigm, and not just certain constructions that have been remembered with a certain verb form.

A lot of the British gotten that I've been exposed to is from homegrown children's television and children, and that's what really seals it for me as a 2019 word. After 20 years of not hearing it much (and training myself out of saying it much), I'm really noticing it. You can find lots of people, particularly older people, in the UK talking about its ugliness or wrongness, but the fact that younger people are un-self-consciously saying it makes me think that it will get bigger still.

And on that note, a bit later than is decent, I say goodbye to 2019!

Footnotes:

* I haven't presented corpus numbers in this post, since the bulk of the gotten numbers in corpora tend to be (in news) quoted Americans or (in other things) in set phrases. The Hansard corpus tool at Huddersfield University doesn't seem to be able to separate the gottens from the ill-gottens—which is a form that has remained in BrE despite the more general loss of gotten.

** (I got quite a few google hits for gotten in the Telegraph, for which I could see the gotten in the preview. But for some, when I clicked through, the same sentence had got. Might this be because some stories were originally posted with gotten then changed when the "error" was caught?)