A shorter (maybe), quicker and earlier post this month, since I am going to be travel(l)ing without much internet access in September and am (orig. AmE) freaking out* about how much work I have to do before the autumn/fall semester begins.

In a recent Language Log post, Victor Mair points out a difference in how American and British teens might react to this shirt:

Americans would tend to say I wouldn't be caught dead in it but BrE speakers would more likely say I wouldn't be seen dead in it.

To me, these bring up different images, since caught is a more dynamic verb than seen. Those who are caught are generally trying not to be caught. I wore the t-shirt, but I wanted to avoid being seen in it. But those who are seen can't help being seen. If you say 'I wouldn't be seen dead in it', it sounds to me like you fear someone putting the t-shirt on you after you've died. But maybe that difference in imagery is just me. Most people aren't so literalist about their idioms.

Anyhow...what's the history of these phrases? The OED has American caught dead from 1870 and American seen dead in 1887, then a Scottish-authored found dead in 1923, followed by British seen deads in the 1930s. So it's likely it started in the US, but then got translated a bit in UK.

|

| from the OED |

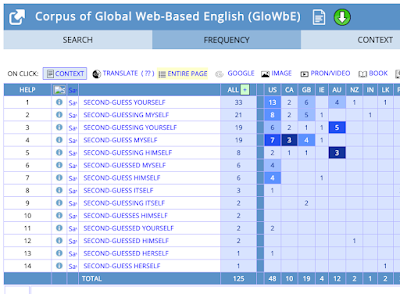

Other 'be caught ADJECTIVE' phrases are also more American. (In this corpus result, the Token 1 column is number of hits in the US corpus, and the Token 2 column is UK).

|

|

| from the OED |

So, generally, caught is used with adjectives to describe being in a situation you're not prepared for. With a noun, we also have caught by surprise (more than 2x more US hits in GloWbE).

But not all caught + adjective phrases with connotations of unreadiness are more American. Caught red-handed has more UK hits in the GloWbE corpus (less than 2x more), and that makes sense since red-handed is from Scotland in the early 1800s. (The red is the blood of the person you've just murdered.) That's a more literal caught, though—being caught by the police (or someone).

*I've only really just appreciated that anything that looks bold when I'm in the blogger editor doesn't look bold when the post is published—at least not on my browser. So, I'm going to start putting bold things in another colo(u)r just to underscore the difference. If anyone wants to give me a tip on how to retroactively change the font across the blog to make the bolds stand out more, please let me know via gmail (lynneguist).

![Battered metal sign, red with white lettering: G [crown graphic] R – POST NO BILLS](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgi_EiQJLoDLg3jqjh-98pfCVqRk_0tmXPk5LuyEsQoDrJBzW4Bw9w5XecSLWH-o76hhKpVYqZLy8zRxW9MslP8Yg5wR4aYCBu6Muyykiy8qo-uFG1o-oVI_R1YC77pxPo8ervm2ViFHDbSS0ybzSikS5baADHmYxePHDby-natzBkYdbnLV4AQ/w310-h400/Screenshot%202025-08-10%20at%2012.50.18.png)