Fellow American-linguist-in-Britain

Chris Kim mentioned to me the British use of

If I'm honest as a discourse-commentary-type idiom, where she would more naturally say

To be honest. By 'discourse-commentary-type idiom', I mean: it's a set phrase that the speaker uses to indicate their stance with respect to what they're saying in the rest of the sentence. As in:

I think to be honest, like most people would be, he was extremely p***** off with the idea of being ill so soon after retiring! [Mirror.co.uk]

"It makes me a bit nervous, to be honest, and I am handling her with

little gloves at the moment because I am not sure how far to push.”[Brendan Cole on Victoria Pendleton in The Telegraph]

I reckon I see about one production of it every year. Most of them, if

I’m honest, aren’t great. But they keep being staged: audiences can’t

seem to get enough of Greek tragedy. [Natalie Haynes in The Independent]

I'd very much been 'out' as a former geographer. If I'm honest, I'd outed myself many years earlier. [comedian Rob Rouse]

There's also the variant with

being:

I'm fairly happy being both English and British. I don't feel that I need to choose.

If I'm being honest, and with apologies to the other nations of this

country, I think that's because I see the two identities as very much

overlapping - the vast majority of British people are English, and being

English and being British have very similar implications. [Comment on a Guardian article]

But if I'm being honest I had never thought about the spear tackle rules. [sporty person talking about a sporty thing in The Independent]

The

I'm phrases are sometimes--much less often--found in the full form

I am.

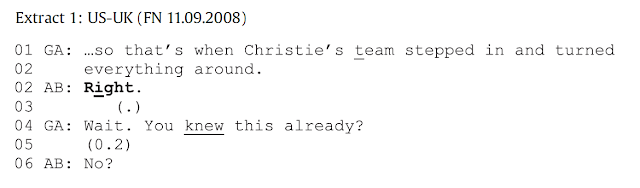

The examples above were all found through the

Corpus of Global Web-Based English (GloWBE). Wiktionary

defines these phrases as equivalent, and

frankly is offered as a synonym. But

frankly doesn't sit quite right with me in all of the contexts. In the examples I've given, the first of each pair has the speaker/writer 'being honest' about something other than themselves. There, I might say

frankly. In the second examples, they are admitting something about themselves. In those cases, I get a sense of 'I'm ashamed to say', not just 'frankly'.

I tend to interpret the BrE ones with

I as having more of this personal reading to it, but I'm not a native user of that form, so my intuitions may be off.

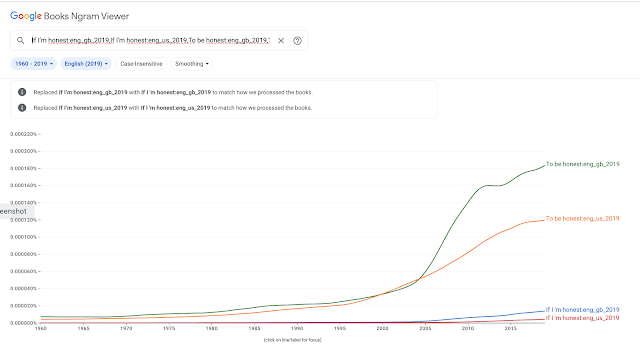

Chris is right that Americans say

to be honest and not

if I'm honest (though it is

the name of a country album), but what's interesting is that the British seem to say all of these phrases more.

I searched for

to be honest followed by a comma or a (BrE)

full stop/(AmE)

period in order to avoid counting things like

I asked you to be honest with me. This might slightly undercount British examples, because Brits are less apt to use commas after sentence pre-modifiers than Americans are, but oh well. (There are some false hits in the numbers with non-idiomatic use of these words, but not many.) The * in the other rows indicates that I've included numbers for

I am and

I'm. (Keep in mind that this is data from the web, so

I expect 15-20% of the data to NOT be by people from the dialect in question.)

|

AmE |

BrE |

| to be honest {,.} |

2700 |

5483 |

| if I *m honest |

91 |

713 |

| if I *m being honest |

35 |

99 |

One has to wonder: why are these such popular idioms in BrE? And then one has to wonder: is it because most of the time people are expected NOT to be honest, so it has to be marked up where people

are being honest? There may be something to that--the British, after all, have

an international reputation for not saying what they mean. (English Spouse is not impressed with this explanation.)

But: against that hypothesis is the fact that one can kind of say the same thing with the simple adverb

honestly, and that's more common as a word in AmE than BrE:

| AmE | BrE |

| honestly | 18600 | 12307 |

Hidden in the

honestly numbers are the use of

Honestly! as an exclamation of exasperation--a word that English Spouse uses (it feels like) constantly. He says it when the child hasn't put her shoes on when asked, when

Jeremy Hunt is on the radio, when he thinks we're going to be late because I can't find my sunglasses. It's not clear whether he's an easily exasperated man or whether he lives in an excruciatingly exasperating climate (i.e. in a house with me).

This is harder to check in a corpus, because corpora are not particularly rich in situations where children haven't put their shoes on after repeatedly being asked. Where one can find standalone

Honestly! in GloWBE, it's hard to tell if it's an assurance of honesty or an exclamation of exasperation.

There are cases that look like the Honestly of exasperation in both the American and British data, but the largest number are in the 'hard to tell without hearing the person' category:

Not the Honestly of Exasperation: It is for sure one of the MOST beautiful things I have ever read. Honestly! It is the gospel lived out in its purest form. (GloWBE-US)

Probably the Honestly of Exasperation:

"Honestly! You can't REALLY expect me to believe that?" (GloWBE-US)

Could easily be read more than one way:

I just started laughing -- honestly! it's been 6+ months since we talked. (GloWBE-GB)

"Style not dynamic enough", the guy said. Honestly!!! (GloWBE-US)

'Yuck! Pass me the sick bag I want to vom!? Honestly!' (GloWBE-GB)

So, this is the kind of thing that I can't tell whether:

(a) It's more common in British English than American

(b) It's not particularly more common in BrE (there's lots of individual variation), but I notice it more in BrE because my spouse (and his mother) are avid users of it.

Nevertheless, there are more standalone Honestly! in the British data than in the American in GloWBE (86 v 52).

Honestly!

P.S. (the following day)

Commenters are doing a good job of specifying the connotations and contexts of these phrases, so do

have/take a look!

One thing some commenters have mentioned is that some would like an adverb before

honest in

to be honest. Here's what the top 10 adverbs look like (just looking at the phrase followed by a comma):

The list stretches to 40 different adverbs, but many have just one or two hits. In total, with an adverb the AmE (287) & BrE (293) numbers are virtually the same, but as you can see, some adverbs are more nationalistic than others. (Who knew the British were so brutal?)

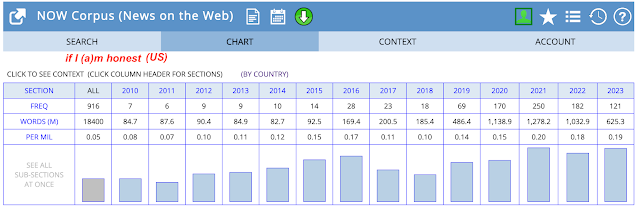

In related 'honesty' news,

@grayspeeks on Twitter asked whether Americans use the expression

(no,) I tell a lie when correcting themselves. The answer is 'no' (GloWBE has 22 in UK, 0 in US), but several US tweeters responded that they'd say

that's a lie or

no, I'm lying for the same thing. It's harder to give accurate numbers for these, because they could be used for other purposes--so I have to look at them with the

no in front, and that creates more (punctuation) problems. Doing that,

no, I'm lying has 3 UK hits and 1 US, as does

no, I lie.

No, that's a lie has 2 UK hits and 1 US one. Those numbers are small enough that I can check by hand: there are no false hits. Trying without the

no gives more false hits than 'good' ones: e.g. people accusing others of lying for

that's a lie or people lying down for

I'm lying. I'm not going to go through hundreds of examples to try to count whether AmE is saying these phrases more--just not with

no--because there's just too much guesswork in judging them. So, it's not a clear picture, but the evidence we have has BrE using all the

lie phrases more than AmE.

One that Americans do seem to use more is

to tell (you) the truth , (thanks, Zouk Delors, in the comments). US hits = 366, UK = 188.

_by_Blake_Shelton.png)