The annual preamble (you can make that rhyme if you try hard enough)

Each year since 2006, this blog has designated Transatlantic Words of the Year (WotY). The twist is that I choose the most

'of the year' borrowings from US-to-UK and from UK-to-US.

This year's WotY posts are a bit later than usual. Had I had strong ideas about which words to crown, I might have written the posts during my Christmas (BrE) holiday/(AmE) vacation, but I didn't, so I thought I'd wait till I was on the plane back home on New Year's Day. Except that I didn't get on a plane on New Year's Day, and the travel woes got more and more complicated after that. A few days' recovery was needed. So I'm taking the opportunity to announce my Words of the Year on the Zoom programme/show That Word Chat on 11 January, and this post will post at that time.

During the 2020 WotY season, I was very interested in the variability of the language for our universal experiences of the early pandemic. Isolation, lockdown, and quarantine were Words of the Year from different English-speaking nations, but generally referred to the same thing. (In the latest issue of the journal Dictionaries, which I am hono(u)red to edit, Wendalyn Nichols and Lewis Lawyer tell the tale of how the WotY process led Cambridge Dictionary to record new senses for quarantine.) By the end of the year, there was hope of a vaccine, a word that ended up being or inspiring several dictionaries' 2021 Words of the Year. But BrE jab had already poked its head into the US in December 2020, thanks to Oxford-Astra Zeneca's early vaccine successes, so it was my 2020 WotY. Since then the transatlantic vocabulary traffic has seemed rather calm. With all of us glued to our computers and our streaming services, you'd think that words would be happily travel(l)ing while we stayed (at) home. But no. It was really difficult to find clear candidates for the 2021 SbaCL WotYs.

Eligibility criteria:

- Good candidates for SbaCL WotY are expressions that have lived a good

life on one side of the Atlantic but for some reason have made a splash

on the other side of the Atlantic this year.

- Words coined this

year are not really in the running. If they moved from one place to

another that quickly, then it's hard to say that they're really

"Americanisms" or "Britishisms". They're probably just "internetisms".

The one situation in which I could see a newly minted word working as a

transatlantic WotY would be if the word/expression referenced something

very American/British but was nevertheless taken on in the other

country.

- When I say word of the year, I more technically mean lexical item of the year, which is to say, there can be spaces in nominations. Past space-ful WotYs have included gap year, Black Friday, and go missing.

And as we shall see this year, I'm even willing to go

sublexical. So without further ado...

The UK-to-US Word of the Year: university (= AmE college)

Now, of course, the word university is general English and has been in use in the US for a very long time. (The University of Pennsylvania has been so called since 1779.) So rather than talking about the importation of a word, we're talking about AmE adopting a BrE sense/usage for a word form it had already. (We've certainly had WotYs like that before, including jab, ginger, and bump.)

What's changed is that US people are talking about their higher education place/experience as university more than they used to. Back in my day (I hope you read that with a suitably wavering voice), we always called it college, no matter whether the institution had college or university or institute or maybe something else in its name. And, of course, that's what Americans mostly still do.

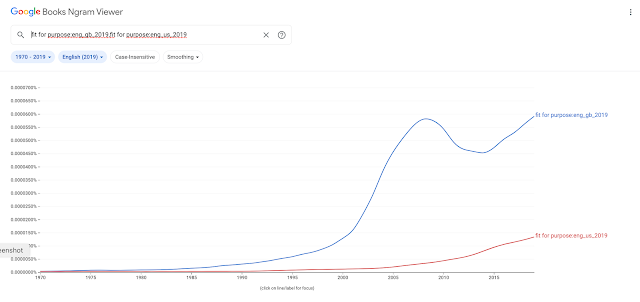

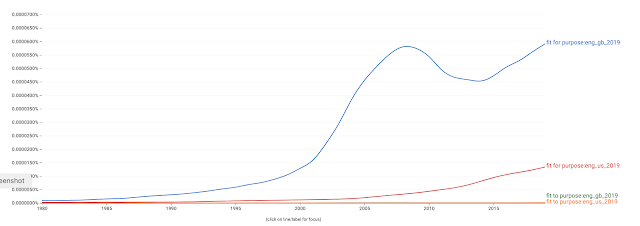

But some Americans seem to be saying university in some of those contexts, particularly after the preposition in. The News on the Web (NOW) corpus has three US examples of in university for 2011 (from just two sources), but over 20 for 2021. The turning point seems to have been 2019, but 2021 showed us it wasn't going anywhere. Here's a poorly formatted sample (I'll try to fix it later):

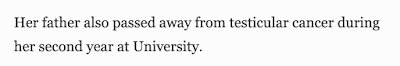

But in BrE, it would be at university in most of those contexts:

Rather than borrowing the BrE expression at university, AmE is using that BrE sense of university in the same prepositional contexts as AmE uses college:

One does find some relevant examples of

at university in AmE, but there something interesting is happening. Note the capitali{s/z}ation in this tweet:

Forbes magazine has a couple of 2020 uses, both by non-Americans about non-American subjects—but what's interesting is the American-seeming capitalization—probably not how the BrE/AusE-speaker authors would have written it.

There seems to have been some sense in 2020 that University was in some way an abbreviated name or title of the place. I was trained in AmE to capitali{s/z}e the 'u' when referring to a particular institution as an institution, but in those cases (in AmE) it was always preceded by

the. For example, my employment contract would be between me and

the University. But in the more BrE-like usage, it's not preceded by a

the and so Americans don't quite know what to do with it. In AmE, you would study

at the University of Pennsylvania, but when you do so you're

in college. We're not quite ready for

at university, even though we're happy with

at school. [See this old post for discussion of the different meanings/uses of school, college and university in the two countries, which will cover at least half of the things that you might be itching to mention right now.]

As well as familiarity with BrE university, I wonder if part of the motivation for this change-in-progress is a new division of labo(u)r between community colleges and universities. When I went (BrE-from-AusE) to uni, it was usual to apply to a four-year college/university and go for four years (or so). But changes to the costs of higher education have led many Americans to take their first year or two at a community college (see that old post again) and transferring their credits to a bachelor-degree-granting institution after taking their (AmE) general education courses at a cheaper, more local place. Maybe the distinction between a place where you get some tertiary-level credits and where you can get a bachelor's degree seems more relevant now. This is just supposition, but it could be investigated...

This WotY was inspired by Ben Yagoda's posts on his Not One-Off Britishisms blog and his tweets on the topic. As well as noticing preposition+university, he's also been tracking university students, as a synonym for college students in AmE. I don't want to repeat all his good work, so please see his posts on related topics here. When I asked him yesterday what he'd pick if this were his WotY decision, he chose university. Luckily, I'd already started writing this post!

Thanks to Ben for all his great, year-round Britishism-in-America

tracking, to Mark Allen at That Word Chat for letting me announce my

WotYs at his (orig. AmE) shindig, and thank you for reading! To read part 2 (UK>US) click here.