More than once, I think, veteran or (the noun vet) has been nominated for US>UK Word of the Year. Dru, who nominated it for 2022, felt that it was appearing more often in UK contexts:

The word I’d propose is ‘veteran’ in the US sense of a former soldier. Some may dispute this as a word for this year as many of us have long been aware of it as an American expression, but since the summer of this year, I’ve increasingly heard it used on the BBC and elsewhere to meaning a former member of the UK armed services.

In the UK hitherto, it has just meant ‘old’, possibly slightly distinguished and used of cars etc.

The US abbreviation ‘vet’ causes confusion here as ‘vet’ means a doctor for animals, short for veterinary surgeon.

I considered making it the WotY, but it didn't feel 2022-ish enough. (You'll see why below.) But I put it on my to-be-blogged-about-sooner-rather-than-later list, and here we are! If you don't want to see all (BrE) my workings, scroll down to the TL;DR version.

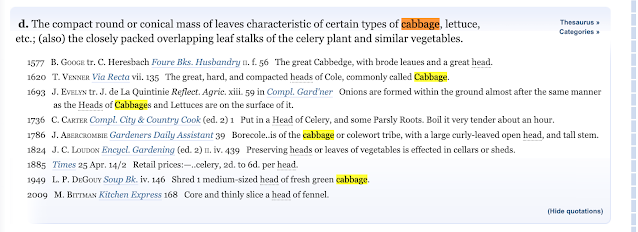

The ex-soldier sense of veteran wasn't made up by Americans. Since the 1500s, veteran has been an English noun referring first to someone with "long experience in military service or warfare" (Oxford English Dictionary sense 1a) or "an ex-member of the armed forces" (sense 1b). Note the difference there: in the 1a meaning, the person is still probably serving, whereas in the 1b meaning they're retired from service.

That second (1b) meaning, the OED notes, is "now chiefly North American," though there are UK examples peppered through their timeline of quotations.

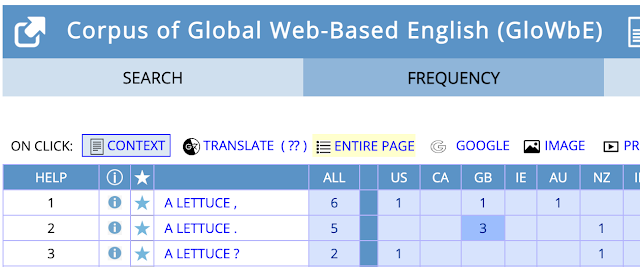

In BrE it is still used for sense 1a, to refer to old-but-still-going things or people. It's sometimes used like that in AmE too, often in relation to theat{er/re}, as in a veteran of stage and screen. The usage that Dru mentioned, veteran car, is particularly BrE. In AmE, you could call such a thing a vintage car (as in BrE too) or an antique car, as shown here in the GloWbE corpus:

It's tricky to investigate whether the ex-soldier meaning of veteran is going up in BrE usage because how much we talk about veterans varies a lot according to what's going on in the world. But to have a little look-see, I searched for the phrase "war veteran(s)" in Hansard, the record of the UK Parliament. There is almost no usage of the phrase before 1990, then a lot more in 2000–2009.

Now, maybe some of these are in sense 1a, the 'been serving for a long time' sense. But a peek at the data shows that most of the 2000s examples relate to compensation for Gulf War veterans, so it does seem to be more the ex-soldier meaning. Note that [more AmE] WWI/WWII veterans are usually called First/Second World War veterans in BrE, and there was the Falklands War after that, so it's not that there were no "war veterans" before the 1990s.

A different tool, Hansard at Huddersfield, takes us up to 2021, and there we can see that this use of veteran appears to have stabilized, rather than continuing to increase. But in Covid Times, it's likely that there was just less debate about ex-servicepeople in Parliament—so we can't make too much of that stability. It could be increasing in comparison to other ways of talking about ex-servicepeople.

What about vet?

I've written about vet before—in fact it was my 2008 UK>US Word of the Year. But in that case it was a verb (as in to vet a candidate). Now I want to just look at the noun—or nouns.

Vet can be short for (more AmE) veterinarian/(BrE) veterinary surgeon. You take your pet to the vet. It rhymes and everything. Let's call that vet1. The OED has examples going back to 1862, and marks it as "chiefly British", which, as we're going to see, might not be the best way to describe it.

In AmE since the 1840s, vet has been used as a shortened form of veteran. Let's call that vet2.

In AmE, where both are used, context is usually enough to tell the difference between vet1 and vet2. You take your dog to the vet1. People study at vet1 school. But a Vietnam vet is probably a vet2 and not a Vietnamese vet1.

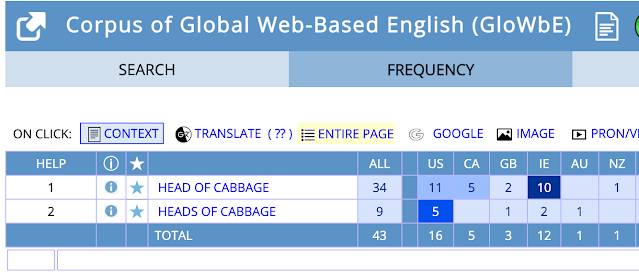

Both vets are well-used in AmE. I used english-corpora.org to take a 100-sentence sample of the noun vet from the Corpus of Contemporary American English. Of the 100, 57 definitely referred to the animal doctor, 23 referred to former soldiers, 3 referred stage or other veterans, and 6 were neither of these nouns (1 verb, some acronyms, a typo, and a Dutch word). That leaves 11 where I couldn't tell in the very brief window of text which vet it was; it referred to a person who'd been introduced earlier in the text. Had I had the full text, I assume there would be close to zero ambiguous cases—but even with a very short window of context, it was usually easy to tell. (For some examples, see below. Click to enlarge.) In any case, note that the majority refer to the animal doctor. I had a quick peek in the Corpus of Historical American English, and the phrase "to the vet" (as in I took my dog...) is there since the 1940s, increasing in use each decade.

While the singular was usually the animal doctor in AmE, in the plural, vets, it's more likely to refer to former soldiers, since they are more often discussed as a class than veterinarians are.

So, as is often the case for homonyms, context usually tells us which thing we mean.

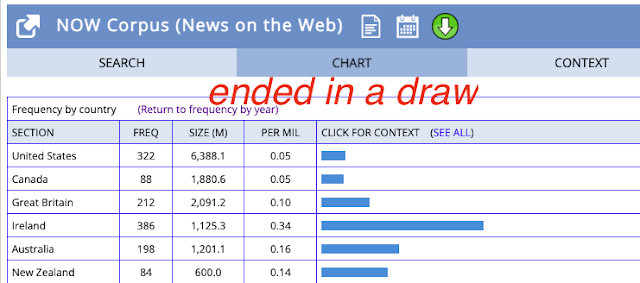

Is the use of vet2 increasing in BrE? Well, probably some, but it's harder to find good evidence for it. There are scattered uses of war vets in Hansard since the 1960s, but it's probably too new and informal to be used in parliamentary talk. When I was researching it as a possible Word of the Year, I looked at samples from the News on the Web corpus, and found 5 examples (of 100 vet) in 2011 and seven in 2022 (the highest years were 2019 at 11 and 2020 at 20, but there were only 3 in 2021). My small sample size could have skewed things (but it was as much as I could give time for). A lot of the UK examples I looked at were about American vets, in which case the UK news source could have been quoting an American person or possibly publishing text from a wire service, possibly originally written by an AmE speaker. So, as I say, it's not simple to spot the truly BrE usage.

TL;DR version

The full form veteran (in the ex-soldier sense) is definitely used in the UK these days. Though it is now perceived as an Americanism, it originally came from Britain, and it probably never entirely went away there.

Vet as an abbreviation of

veteran, originates in AmE, and is still used there.

Vet as an abbreviation for veterinarian/veterinary surgeon is originally BrE, but has been well used in AmE for a long time (or at least, throughout my lifetime!). The ambiguity this creates hasn't been a huge problem. No one's mistakenly taking their dog to

the VFW.

![GloWbE corpus shows plenty of instances of "here/we at [something] towers" in British English, none in American English are in](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjejOA3LXlR-A4szzgMNbegSCf9I9jkxajJpgVtnQ6NuChRcPZJwUkdQVsmXVETbCRrRVxe3q_EUzdduuzTiYuzk64x_aGKKl88G85ZDhWXzF_dK6Hj1ZYdJ9litLoDD0vNJPa8oL9sBwGYIWio9nFS-kojNelKXMReks6rY5KRsHoOGaH3TQ/w549-h640/Screen%20Shot%202022-11-20%20at%2011.29.35.png)