For part 1 of 2020 Words of the Year, click here.

In recent years, I've had a good slate of candidates for UK-to-US Words of the Year, but something seemed to happen to transatlantic word travel in 2020. You might think that an internet-age pandemic would make the world more open to words from elsewhere. We're all in the same boat. We're talking about it on social media. We're watching a lot of the same program(me)s on Netflix. But, as we saw for terminology for isolation/lockdown/quarantine, the pandemic has shown how local linguistic preferences still grow and thrive in the Anglosphere. In fact, those three terms made it as Words of the Year for different dictionaries in different places: the Australian National Dictionary Centre chose iso (for isolation), Collins (UK) chose lockdown, and Lexico (US-UK hybrid) and Cambridge (UK w/ strong US presence) chose quarantine.

You'll have already seen in the title that the UK-to-US Word of the Year is:

jab

I thank my friend Paul for sending me this fitting memorial of the moment:

|

| From @birdyword on Twitter |

But before I write about why and how jab got the title, I'd like to review the strange year it's been for UK-to-US word transit.

During the year I noted words that I wanted to remember when it came to WotY time. Before Covid became a pandemic, my money had been on rubbish, particularly in its grammatically malleable usage to mean 'not good': e.g. as an adjective a rubbish idea and as a verb: don't rubbish my idea. Americans were using it a lot in 2019. But then, it crashed:

Another one to consider had been reckon, a verb that is present in AmE and BrE, but limited to regional usage (and possibly lower registers) in AmE. Here we're interested in its particular use where other AmE registers might use figure or suppose. The fact that it's not low-register in BrE can be seen in the fact that I reckon has been much-said in recent-ish decades in the UK Parliament:

Ben Yagoda had blogged about this one twice in 2020 on his Not One-Off Britishisms blog,

so it seemed like a good candidate. But was it coming over from BrE or

was it coming "up" from American dialects? Yagoda's examples in the

press made the BrE argument: lots of Britishisms come in through the New York Times and the Washington Post, etc., because they're written by well-travel(l)ed, cosmopolitan, word-loving, and often foreign people. His reckons looked like that.

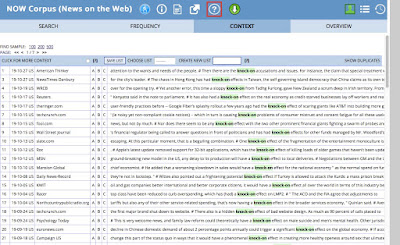

But when I looked at American reckon examples in the News on the Web corpus, I found a lot of cases where Americans, particularly African Americans, were being quoted in relation to local matters. That made me more suspicious of the increasing numbers of reckons in the corpus data. Maybe it wasn't people sounding more British, maybe more speakers of varied dialects were being quoted in the news this year (and there were plenty of reasons for that to happen this year).

And then there was also the 2020 effect. Reckon was showing up lots in the NOW corpus in 2019, and then it went down in 2020. (Its up-and-downness might well be a product of its regionality.)

So, it ends up looking like AmE is turning away from BrE a bit this year. With all that was going on in the US in 2020, perhaps this is not all that surprising.

So, we ended up with jab as a very late contender for WotY, showing up in December when the UK approved the first vaccine for Covid. (This is why one shouldn't do one's Words of the Year in November, dictionaries!) It's hard to do a corpus search that includes only the 'inoculation' or (AmE) 'shot' sense of jab and not senses to do with poking and hitting of the manual or verbal type. But the December doubling of jab in American news is clearly due to the BrE sense of the term:

Again, Ben Yagoda covered this one at his blog. Here's what he had to say:

Unsure that I wanted to crown such a late entry as WotY, I ran a vote on the matter at the online event I did for Atlas Obscura on 19 December. I was hoping to show you the vote result, but the Zoom polling screen doesn't show up in the video that AO shared with me. What a pain! So all I can tell you is that jab was the clear winner against rubbish and reckon. Will it remain a word-in-the-news about inoculations elsewhere, or will Americans start using it as a synonym for shot? Remains to be seen.

And thus I close the 2020 SbaCL WotY celebrations. Do keep your eye out in 2021 for the words you'll want to nominate this time next year!