Reader Sam Fox wrote in with the question:

I am an American, a Midwesterner all my life, though I have traveled quite a bit..

On a recent visit to London I was surprised to hear the word “crescent” in the tube stop Mornington Crescent pronounced with a z rather than s. I think I heard other examples of unexected intervocalic voicing. Is this something you have noticed?

I have noticed it, particularly since I've had the word crescent is in my address. But I was surprised to find that UK dictionaries don't seem to agree about it at all.

In the /s/ camp:

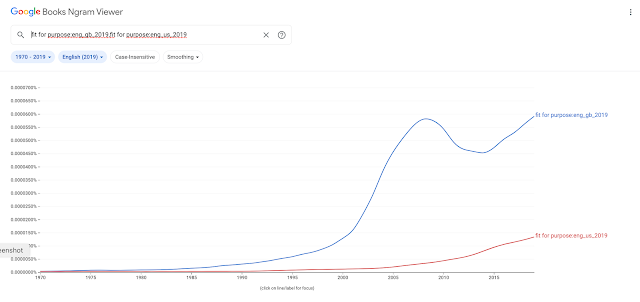

- The Oxford English Dictionary (a historical dictionary) [first picture]

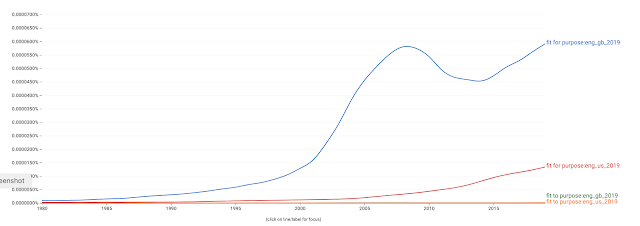

- Google [picture 2]

- Cambridge

- And all of the American dictionaries (Merriam-Webster, Webster's New World, Dictionary.com, American Heritage)

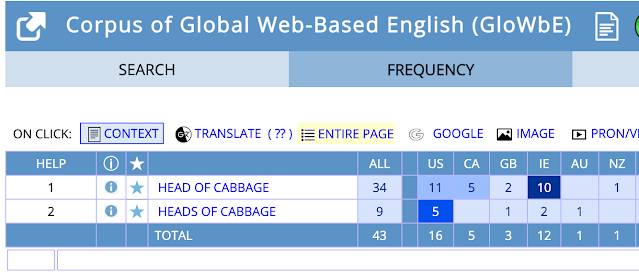

In the /z/ camp:

- Lexico (which comes from the people at Oxford Dictionaries)

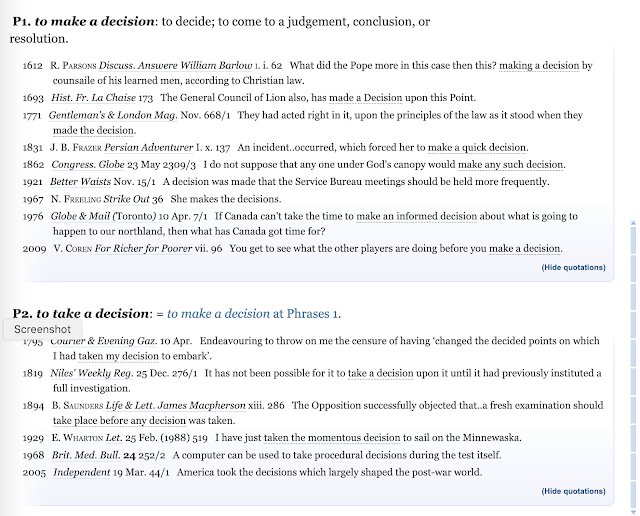

- Macmillan (picture 3)

And presenting both, always with /z/ as the second option::

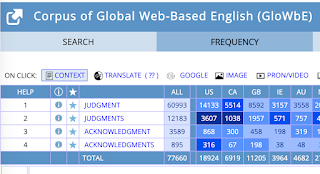

- Collins, in both their English dictionary and in the COBUILD (learner's) dictionary. (picture 4)

- Longman

Since the OED has only the /s/ and since /s/ > /z/ between vowels is the more likely phonological process, we can assume that the /z/ is somewhat new compared to the /s/, and so it's particularly interesting that two of the British sources only have the /z/. If anyone in the US says it with a /z/, I don't know about them. So we can say that this /z/ is a BrE pronunciation, but not the BrE pronunciation. (When it comes to pronunciation, there's probably next to nothing that one can count as the BrE.)

So how prevalent is the /z/ in the UK? And who says it?

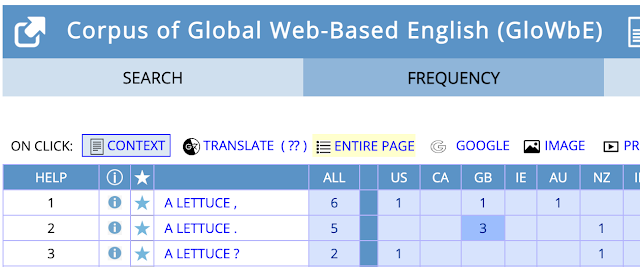

I listened to more than 50 examples on

YouGlish, discounting a few along the way because they were the same person again or the person seemed not to have a UK accent. Of the 47 I counted, 23 had /z/, 23 had /s/, and one, by

Alan Bennett, I just couldn't tell. So the dictionaries that have both seem to have good reason for it.

At first, I was getting mostly /s/ and I thought that it was because there were a lot of 'posh' voices giving lectures about the Fertile Crescent. But as I went on, it became clear how varied the speakers who say /s/ or /z/ are. Both were said by young and old. Both were said by fancily educated people. There were a couple of Scottish voices that said /s/, but other than that it felt like both /s/ and /z/ were hearable around much of England. Among the /z/-sayers were

Professor Brian Cox (from near Manchester, in his 50s) and

Jeremy Paxman (in his 70s, born in Leeds but raised in Hampshire and sounding very much like his Cambridge education). I wonder if there are any dialectologists out there who could give us a bit more insight about whether this /z/ is particularly associated with one place or another? It doesn't seem to be a variation that was captured in the

Cambridge Dialect App.

Going beyond

crescent, there are other spelled-

s-pronounced-/z/ cases that contrast between AmE and some BrE speakers. The

Accent Eraser* site lists these ones, a couple of which I've written about before (see links).

- Eraser

- Blouse

- Diagnose

- Greasy**

- Opposite

- Resource

- Vase

- Mimosa

- Crescent

- Joseph (click on the link to see a lot more personal names with this difference)

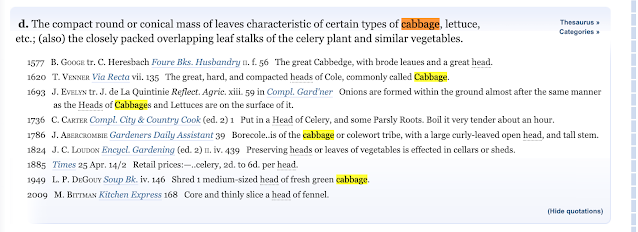

These are lexical pronunciations—that is, speakers just learn to pronounce the word that way on a word-by-word basis, rather than a rule-based pronunciation, where the pronunciation is 'conditioned' by its pronunciation environment and it happens to all words that contain that environment. We can tell this isn't a phonologically conditioned variant because fleecy, which has an /s/ sound between the same vowels as in greasy, is never "fleezy". There's nothing these words have in common that makes them all go toward the same pronunciation—some are between vowels (a place where it's easy for consonants to take on voicing), but others are word-final. Some may have been pushed toward /z/-ness due to their similarity with other /z/-pronounced words: greasy–easy, resource–resort, and the like.

My intuition about them is that they're very irregular across people. I just played a 'guess the word' game with my south-London-born spouse (50s), and he used /z/ for all of these except greasy and opposite, for which he used /s/. Who knows why?

I haven't got the time now to see how regular dictionaries are about their representations of these, but it strikes me that this would make a nice little undergraduate student project!

*Eek! "Accent erasing" is not something a linguist likes to endorse—you can be an accent replacer, but not an accent eraser.

** Forgot to mention: you do hear greasy with a /z/ in AmE. I think of it as southern, someone on Twitter said they think of it as midlands, but a friend from my northeastern hometown says it, so it's kind of irregular too.