This is part 2 of an examination of the words that were very country-specific in Brysbaert et al. (2019)'s study of vocabulary prevalence. For more detail on the study, please see part 1, on American words Britons don't tend to know. This half-table shows the words that British survey respondents tended to know and American ones didn't:

All of the terms will be discussed below, but not necessarily in the order given in the table. Instead, I'll group similar cases together. The unknown items from AmE were overrun with food words—that's less true here, though there are some.

Stationery items

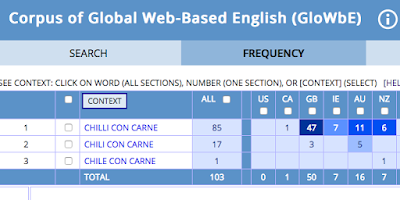

The first two items are generici{s/z}ed brand names for office supplies. Tippex is correction fluid, known in AmE by brand names Wite-Out and Liquid Paper. Tippex is used as both noun (for the fluid) and as a verb for the action of covering things over—literally with correction fluid or figuratively. Here are a few examples from the GloWBE corpus that show some range:

- Her contact details had been TippExed over a number of times.

- make-up, hair extensions, fake tan and tippexed teeth

- But one series of game Tippexed over the old rules

Biro is an old trade name for a ball-point pen, based on the name of the inventor László Bíró. The first syllable is pronounced like "buy" (not "bee").

Amusements

|

| Pic from here |

Dodgems (or dodg'ems) are (orig. AmE) bumper cars. The BrE has the look of a brand name turned to a generic, though it's unclear to me if that name was ever trademarked. The cars were first called dodgems by their inventors, the Stoeher brothers of Massachusetts. This isn't the first time we've seen an American product name become the generic name for the product type in BrE—but I'll let you sort through the trade names posts for others.

Abseil might not quite belong in the amusement category, as it seems more like hard work, but let's put it here. It's a verb from German for a means of descending a mountain (etc.) using a rope affixed on a higher point. Americans use the French word for the same thing: rappel. The idea comes from the Alps, where both German and French are to be found, so it looks like Americans and Brits might go to different areas of the mountain range. (This is a counterexample to my usual claim that the English will take any opportunity to use a French word.)

Food

Chipolata is a kind of small sausage. They've been mentioned already at the pigs in blankets post. The name comes from French, which got it from the Italian name for an onion dish.

Plaice is a kind of flatfish that's common at British fish-and-chip shops. The OED says "European flatfish of shallow seas, Pleuronectes platessa (family Pleuronectidae)", but some other fish (esp. outside the UK) are sometimes called plaice. The name came from French long ago. It shows up in *many* punny shop names.

Korma is a type of very mild curry typically made with a  yog(h)urt-based sauce. BrE speakers generally have large vocabularies of the types of curry that are popular at UK Indian take-aways and restaurants, which often have menus with headings based on the curry type, like this at the right. It (orig. BrE) flummoxed me at first when English friends invited me over for a take-away and I was expected to already know this vocabulary and be able tell them what I'd like without reading the fine-print descriptions of the curry ingredients. The OED tells us korma comes from an Urdu word for 'cooked meat', which itself derives from a Turkish word.

yog(h)urt-based sauce. BrE speakers generally have large vocabularies of the types of curry that are popular at UK Indian take-aways and restaurants, which often have menus with headings based on the curry type, like this at the right. It (orig. BrE) flummoxed me at first when English friends invited me over for a take-away and I was expected to already know this vocabulary and be able tell them what I'd like without reading the fine-print descriptions of the curry ingredients. The OED tells us korma comes from an Urdu word for 'cooked meat', which itself derives from a Turkish word.

Escalope takes us back to French, and the French influence on UK menus. OED defines it as "Thin slices of boneless meat (occasionally of fish), prepared in various ways; esp. a special cut of veal taken from the leg." It's found in menu phrases like veal escalope or an escalope of chicken.

P.S. Thanks to Cathy in the comments we have an AmE equivalent for this, the Italian scallopini. Another case (like courgette/zucchini) of a French-derived food word in BrE and an Italian one in AmE. (The Prodigal Tongue covers this a bit more.)

Slang

Yob is an example of back slang. It's the word boy backwards, and it's used particularly for young men/boys who engage in anti-social behavio(u)r. Hooligans, etc.

Naff is a word that's hard to translate exactly, which is why it has been one of my 'untranslatables' in the past. It's an adjective that refers to a certain kind of 'uncool', or as Jonathon Green defines it: "in poor taste, unappealing, unfashionable, bad" and more recently it's also meant "second-rate, workaday". I've seen Americans get this word very wrong, so best not to attempt it until you've been in the UK for a some time. Some Brits will tell you it stands for 'not available for f***ing', but, as with almost all such acronymic slang tales, that is almost certainly false. Green's Dictionary of Slang gives this for etymology:

[? north. dial. naffhead, naffin, naffy, a simpleton; a blockhead; an idiot or niffy-naffy, inconsequential, stupid or Scot. nyaff, a term of contempt for any unpleasant or objectionable person; however note Polari etymologist WS Wilcox in a letter 25/11/99: ‘I have long believed that naff may well derive from Romany naflo, a form of nasvalo – no good, broken, useless. Since several other Parlary words derive from Romany this is not impossible’; in this context note also 16C Ital. gnaffa, a despicable person]

Brolly isn't in the same slang league as the previous examples. It's a kind of (orig. AmE) cutesie way of referring to an umbrella. As I discuss in some detail in The Prodigal Tongue, this is what BrE speakers say instead of (AmE) bumbershoot, an Americanism that Americans often erroneously believe to be British. That bit of my book is excerpted at Humanities magazine. Have a read and if you like it, maybe buy or borrow the book? (Please?)

Bolshy is an adjective derived from bolshevik, and as such it originally meant 'left-wing, Communist', but these days it's more often used to mean 'uncooperative, obstructive, subversive' (thanks again Mr Green) or 'Left-wing; uncooperative, recalcitrant' (OED). Don't get bolshy in the comments, OK?

The rest

The other items on the list are just too miscellaneous to fit together under meaningful subheadings.

Gazump (and its sister gazunder) have been treated in an Untranslatables post already, so you can read about it there. It's about underhanded (BrE) property/(AmE) real-estate -buying behavio(u)r.

Kerbside is just (AmE) curbside in BrE spelling. Here's the old post about curb/kerb.

Judder is an onomatopoetic verb. Like shudder, but used more often of mechanical things, like engines that aren't working well. Here's an example from the GloWBE corpus: "the bus juddered over potholes". The OED's first citations of it are in the 1930s, so it came into English long after AmE & BrE separated.

Chiropody is used as AmE (and more and more BrE) would use podiatry, though some specialists try to force a difference in meaning between the two (see this, for example). You'll find other sites telling you there is no difference, and that, for the most part is true. The word podiatry was coined in the US and there covered the same things that chiropody covered in the UK. Chiropody comes from the Greek for 'hands' and 'feet', and you can see the similarity with chiropractor, who uses their hands to treat people. What's a bit funny about chiropody/chiropodist is that the pronunciation is all over the place. Some use the /k/ sound for the ch, following the Greek etymology. That's how dictionaries tend to show it. Others use a 'sh' sound as if it comes from French. You can hear both on YouGlish.

Quango stands for 'quasi-autonomous non-governmental organi{s/z}ation'. I remember learning about non-governmental organi{s/z}ations, or NGOs, when I lived in South Africa in the 90s. Apparently NGO has taken off as a term in the US in the meantime (see comments), but not quango. A quango is an NGO that gets public funds to do something that the government wants and maybe has government participants. Google says the word quango is 'derogatory', but I think that depends a bit on your political persuasion. Here's a BBC fact sheet on quangos.

A pelmet is a decorative window-covering that doesn't cover a window—it covers the top of the window and maybe the curtain rail. It can be a little curtain or a kind of box or board. Here's a selection of those that come up on a Google Image search:

The curtainy type of pelmet would be called a valance in AmE—which we've seen before because it has a bed-related use in BrE. I honestly do not know what the boxy things would be called in AmE. I've never had one in an AmE house, and my efforts to find them on US websites have not (orig. AmE) panned out. If you have the answer, say so in the comments and I'll update this bit.

P.S. Thank you commenters! Grapeson offers cornice as an AmE possibility. Usually (and in BrE too) this is a thing at the joint of the wall and the ceiling (often decorative). But Wikipedia has a little section on 'Cornice as window treatment' that confirms this usage. Then Diane Benjamin offers box valance as an AmE alternative. The Shade Store says this:

The primary difference between a curtain valance and a cornice is that valances are made out of drapery or fabric, while cornices are typically made out of wood.

Thanks to the commenters for helping out!

Finally, chaffinch is a bird species  (which didn't come up in the recent bird posts). The Wikipedia map to the right makes it easy to see why Americans didn't recogni{s/z}e the word (the green areas are where chaffinches typically live). Wikipedia does say "It occasionally strays to eastern North America, although some sightings may be escapees."

(which didn't come up in the recent bird posts). The Wikipedia map to the right makes it easy to see why Americans didn't recogni{s/z}e the word (the green areas are where chaffinches typically live). Wikipedia does say "It occasionally strays to eastern North America, although some sightings may be escapees."

So, that's that! Words that most British folk know and most Americans don't. If only I'd had Brysbaert et al.'s list when I was trying to make very difficult AmE/BrE quizzes.