A few years ago,

The Telegraph ran an article about Americanisms on the BBC—or rather, an article about complaints about Americanisms on the BBC:

Nick Seaton, Campaign for Real Education, said: “It is not a

surprise that a few expressions have crept in but the BBC should be

setting an example for people and not indulging any slopping

Americanised slang.”

(Tangent: I had to look up

slopping, which doesn't seem to be used much as an adjective. Is he using the British slang 'dressing in an informal manner' or the American slang for 'gushing; speaking or writing effusively'? Or is

slopping here being used as a euphemistic substitution for another word that ends in

-ing?)

But (

of course!) half of the 'Americanisms' in their closing list of 'Americanisms that have annoyed BBC listeners' weren't Americanisms. One

(face up) was first (to the OED's knowledge) used by

Daniel Defoe, the Englishman. Another (

a big ask) is an Australianism. But one that really bothered me was this:

- 'It might of been' instead of 'It might have been'

Three reasons it bothered me:

- Shouldn't it might of been be corrected to it might've been rather than it might have been? That is, of is a misspelling of the similar-sounding 've here. Might've is perfectly good contraction in BrE as well as AmE. Is the complaint that people should say have because they shouldn't be contracting verbs on the BBC, or are they complaining about spelling 've wrong?

- We're talking about broadcast television and radio, which are spoken media. You

can't see the spelling of what the presenters are saying. So how do they know the presenters said might of and not might've? Of course, they could have seen it on the (orig. NAmE) closed-captioning/subtitles.

But BBC subtitles usually make so little sense that I can't believe

anyone would take them as an accurate record of what's been said.

(Here's a Daily Mail collection of 'BBC subtitle blunders'.)

- I read of instead of 've a lot in my British students' essays. A lot. There's no reason to think they're getting it from American influence, because they'd have to read it and they probably don't get the chance to read a lot of misspel{ed/t} American English. The American books or news they read will have (we hope) been proofread. I suspect that errors like this aren't learn{ed/t}from exposure at all: they are re-invented by people who have misinterpreted what they've heard or who have a phonetic approach to spelling, sounding out the words in their minds as they write.

This particular

Telegraph list is one of the things that I mock when I go

around giving my

How America Saved the English Language talk. But so far, when I've talked about it, I've just said those three things about it. I have never looked up the numbers for who writes

of and who writes

've after a

modal verb. I think I've been afraid to, in case it just proved the

Telegraph right that it's a very American thing.

I need not have feared! Not only was I right that I see it a lot in the UK, I was also right to feel that I probably see it more in the UK, because —you know what?— the British spell this bit of English worse than Americans.

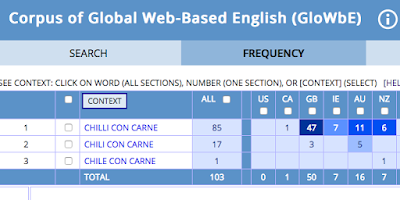

Here are the numbers from the

Corpus of Global Web-Based English. The numbers stand for how many times these variations occur within about 387 million words of text from the open internet.

| non-standard of |

American |

British |

| might of |

392 |

672 |

| would of |

926 |

1634 |

| could of |

458 |

821 |

| should of |

442 |

683 |

| standard 've |

American |

British |

| might've |

506 |

277 |

| would've |

4921 |

3121 |

| could've |

2379 |

1502 |

| should've |

1685 |

1140 |

I've put the higher number in each row in

blue bold in my table in order to reflect how it shows up in GloWBE. The blue-bold indicates that those numbers showed up in the darkest blue in the GloWBE search results, like the GB column here:

|

| (The Canadian numbers are distracting—they're not based on as much text as GB and US.) |

The darker the blue on GloWBE, the more a phrase is associated with a particular country. So,

it's not just that the of versions are found in BrE—it could be said (if we want to be a bit hyperbolic) that

they are BrE, as opposed to AmE.

In both countries, the

've version is used more than the misspelling. Nevertheless, the American numbers were darkest blue for these spellings—indicating the correct spellings are more "American" in some way—though note that the British

've versions are just one shade of blue lighter—the difference is not as stark as in the previous table.

The moral of this story

It looks like the BBC complainers and the

Telegraph writer assumed MODAL+

of was an Americanism because they disapprove of it. But remember, kids:

Not liking something is not enough to make it an Americanism.

Coulda, shoulda, woulda

When I discovered these facts, I immediately tweeted the

would of (etc.) table to the world, and one correspondent asked if the American way of misspelling

would've isn't

woulda. The answer is: no, not really. Americans might spell it that way if they're trying to mimic a particular accent or very casual speech (

I coulda been a contenda!). It's like when people spell

God as

Gawd—not because they think that's how to spell an almighty name, but because they're trying to represent a certain pronunciation of it. No one accidentally writes theological texts with

Gawd in them. But people do write

would of in formal text 'accidentally'—because they don't know better, not because they're trying to represent someone's non-standard pronunciation. In the

Corpus of Contemporary American English, 75% of the instances of

coulda occur in the Fiction sub-corpus; authors use it when they're writing

dialog(ue) to make it sound authentic.

But you do get coulda, shoulda and woulda in an AmE expression, which accounts for about 10% of the coulda data. I think of it as shoulda, coulda, woulda, but there does seem to be some disagreement about the order of the parts:

The phrase can be used to mean something like "I (or you, etc.) could have done it, should have done it, would have done it—but I didn't, so maybe I shouldn't worry about it too much now". (A distant relative of the BrE use of

never mind.) Sometimes it's used to accuse someone of not putting in enough effort—all talk, no action.

The English singer Beverley Knight had a UK top-ten single called

Shoulda Woulda Coulda, which may have had a hand in populari{s/z}ing the phrase in BrE (though it's still primarily used in the US).

Another

shoulda that's coming up in the GloWBE data is

If you like it then you shoulda put a ring on it. And I can't hear that now without thinking of Stephen Merchant, so on this note, good night!

—————

Postscript, 5 Feb 2016:

@49suns pointed out that I haven't weeded out possible noise from things like

She could of course play the harmonica. Good point. British people do write

could of course (etc) more than Americans do because they use commas less. Americans would be more likely to write

could, of course, play the harmonica—and with the commas it wouldn't be caught by the search software. As well as

of course, there's

of necessity and other things 'noising up' the data.

I'm

not going to re-do all the tables because I've posted this now and many

have commented on it. But the good news (for this post) is that the

conclusions about

of is pretty much the same if we limit the search to modal +

of + verb; it's still more frequently British—especially when preceding

been, the case that was complained about in

The Telegraph. Here's a sample.

An interesting case at the bottom is

should of known, which reverses the pattern. This is just because

should [have] known—often in

should [have] known better—is a much more common phrase in AmE than in BrE. Searching

should * known, we get:

Looking more closely at that group, I found that 6 of the 21 American

should of knowns were from song lyrics (none of the UK ones were), and one was using it as an example in telling people that they shouldn't write

should of.

The online interface doesn't like me searching for modal+

of+verb, so I've had to search for *

ould+

of+verb, leaving out

might and in the post I also left out

must. But having re-searched those, I can tell you: still dark blue in British, not in American.

The other thing I haven't done, which someone (or someones) else has suggested is what happens after negation

. That is a lot more complicated, since there are more variations to consider (since both the

n't and the

have can be contracted). I'm really interested in that, so I'm going to write a separate post on it next week. Till then!

Not something I knew till Simon Koppel pointed it out to me, but there are technical terms for those places in the (BrE) pavement/(AmE) sidewalk where the curb/kerb is lower to make it easier to cross the road/street, especially for those using wheels to do so. In AmE these are curb cuts and in BrE dropped kerbs.

Not something I knew till Simon Koppel pointed it out to me, but there are technical terms for those places in the (BrE) pavement/(AmE) sidewalk where the curb/kerb is lower to make it easier to cross the road/street, especially for those using wheels to do so. In AmE these are curb cuts and in BrE dropped kerbs.