We went for a walk with the neighbo(u)rs, and we saw this sign.

The sign reads "Permissive Footpath avoiding Golf Course", and all the adults in our group (2 English, 1 Spanish, 1 American) found the sign amusing. Jokes about what kinds of permissive activities we might find on the path (or that we might find the path doing) resulted, as well as a conversation about what the sign meant and whether it could have been phrased better.

You can tell from this that we're not seasoned country walkers, we're just lockdown people finding new ways to get some exercise. The term

permissive footpath is a term of art in the British land-use bureaucracy, and such signs can be found on many paths. It differs from a

public footpath in that the land is privately owned. The landowner is permitting people to walk on their path. This

explanation of the term offers other expressions like

permitted footpath and

concessionary footpath, but these seem to be much less common, and we would not have been able to joke as much about them. (For those puzzled by our amusement:

permissive usually means 'characteri{s/z}ed by great freedom of behavio(u)r', which can include 'sexually liberated'.)

So,

permissive footpath is not something you'd see in AmE, but that's because there's a lot different about leisurely

country walks in the two countries. And this is why this post has taken a couple of weeks to write...

walking verbs

Let's start by mentioning (it has come up on the blog before) that to hike is usually considered an Americanism, in the sense that it's widespread and "standard" in American English, but it's only ever been a dialect word in the UK. The OED cites an 1825 dictionary of west-of-England dialects as one of its earliest sources for it.

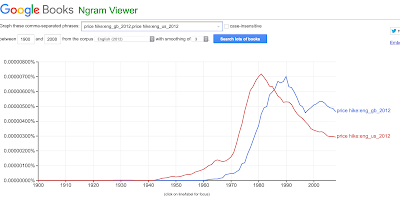

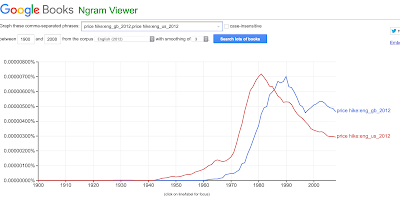

While it's been coming back to the UK, all of its senses were more common in AmE first, for example the noun use as in go for a hike and the more figurative use in hike up a price. Some of the figurative uses seem more common in BrE corpora now, though. You can see the change in this Google ngram for price hike, where the red line indicates the phrase in AmE books and the blue in BrE. It looks like the kind of pattern you'd see with parents and slang...they start using the word when the kids are already moving on to a new one, then carry on using it at a higher rate than those who made it up.

In BrE, those who hike as a regular pastime are often referred to as ramblers, but it's far more common to talk about walking than rambling. (Rambling and Rambler tend to be used in the names of walking clubs, such as the Essex Area Ramblers, who are responsible for the website that taught me about permissive paths.) Of course, English-speakers everywhere use the verb to walk. But for me (at least) what's different is that I have a town/country divide in my AmE: If I'm walking around town for leisure, I'm going for a walk. If I go out of town to walk (on less even terrain, taking more care with my footwear and supplies), I'm going hiking. Or maybe it's better characteri{s/z}ed as: if I'm on a paved path/road or the beach, I'm on a walk, and if I'm on less even terrain (fields, woods, mountains, deserts), I'm on a hike.

footpaths/trails/ways

In its broadest use, any way that's made for walking is a

path or a

footpath, but the word

footpath is much more common in BrE than in AmE. A

footpath can be urban or rural, but is usually distinguished from the

(BrE) pavement/(AmE) sidewalk by being narrower, unpaved, or not running parallel to the road. For instance, a marked "public footpath" in my mother-in-law's suburb is a paved path between houses that let people take a shortcut to the (BrE)

railway station, but the "permissive footpath" above is a (AmE in this use)

dirt path through a wooded area.

|

Click to enlarge

|

Path and

pathway are a normal things to call places where people can walk in either country. The GloWBE corpus has a bit more

path in AmE than BrE, but I'm not going to to through and find out how many of them refer to the

PATH (Port Authority-Trans Hudson) trains in New York.

Pathway is about the same in both.

For places to hike, trail is more common in AmE. This is again difficult to do a corpus chart for, because there are lots of other uses of trail (what a snail leaves, a trail of clues, etc.). (It originally referred to things that trailed behind, like the train of a dress or coat.) But if we look at which words occur before trail in the two countries, we can see a real tendency for trails to be walking places. Many of these relate to names of famous places to hike, such as the Appalachian Trail.

|

| Click to enlarge |

In AmE I'd use

trail as a common noun to talk generally about hiking paths. I've just asked the English spouse whether he'd use

trail to refer to some of the English ones we know, and he says "No, that's American. That's why we don't understand

trail mix. According to the OED, this sense of

trail is:

A path or track worn by the passage of persons

travelling in a wild or uninhabited region; a beaten track, a rude path.

(Chiefly U.S. and Canadian; also New Zealand and Australian.)

The US has a

National Trails System, established in 1968, which includes Scenic Trails and Historic Trails, all of which have

Trail in their name. (See the link for the list.) England and Wales now also have something called

National Trails, but that was only founded in 2005, and does look like a case of UK government borrowing an American idea with its language. Most of the "long-distance footpaths" included in the National Trails are named

Way: the Cotswold Way, the Pennine Way, the South Downs Way. Some are called

Path, e.g. Thames Path, Hadrian's Wall Path. None are called

trails.

Scotland has

Scotland's Great Trails, formerly known as

Long Distance Routes. The rebranding seems to have happened sometime in the past 10 years. Unlike England's National Trails, some are actually named

trail, and those names seem to pre-date the national rebranding, raising the question of whether

this sense of

trail is longer-standing in Scotland.

It's not uncommon to find commonalities between Scotland or Ireland and the US—not necessarily because of more recent Scottish/Irish immigration to the US than English immigration. The similarities can be there if the meaning was formerly widespread in English English, but then went out of fashion in England. However, the OED only has examples of this sense of trail since 1807, which makes it more likely that it might have started in the US and been fed back to the UK. Hard to know without much more work than I can put into this!

Related posts

I've written some other posts that cover related concepts to these ones. If you have comments about those terms, please comment at those posts, where it will be much more useful to their readers.

The first two are pasta-related. Manicotti are a kind of large tube pasta, which are stuffed, usually with ricotta, to make the dish pictured to the right. The name is used both for the empty pasta and for the dish. It comes from the Italian for 'little sleeves', but is, according to Wikipedia, "an Italian-American dish". BrE speakers are more likely to know the very similar pasta/dish canneloni, which is also found in the US and Italy. The difference? "Manicotti tubes are ridged, larger and slightly thicker. Cannelloni tubes are smooth, a touch smaller and slightly thinner."*

The first two are pasta-related. Manicotti are a kind of large tube pasta, which are stuffed, usually with ricotta, to make the dish pictured to the right. The name is used both for the empty pasta and for the dish. It comes from the Italian for 'little sleeves', but is, according to Wikipedia, "an Italian-American dish". BrE speakers are more likely to know the very similar pasta/dish canneloni, which is also found in the US and Italy. The difference? "Manicotti tubes are ridged, larger and slightly thicker. Cannelloni tubes are smooth, a touch smaller and slightly thinner."*