Soon after the Brexit vote, I started writing a blog post about the different usage of the term racial in AmE and BrE. This followed an incident that the UK press had label(l)ed 'racial abuse' against a North American in Manchester. I thought it odd that being abusive to an American counted as 'racial abuse'. I then abandoned the post when I discovered that I'd had it wrong: the abuse was related to the colo(u)r of the person's skin. (There was a "go back to Africa" that I hadn't heard the first time I'd seen the recording.) I still had a feeling that I sometimes heard racial and racist being used differently in BrE than in AmE, but that wasn't an example of it.

But one thing I did find was that one hears the word abuse in such contexts a lot more in the UK. In the green you can see which adjective+abuse combinations are particularly American (left column) and particularly British (right). (Pink means the opposite—much more typical of the other country.)

Much of the 'abuse' in the right column (after anti-semitic, racist, homophobic) can be understood to be verbal in nature. (Worth noting: the word abuse is no more common in BrE than in AmE--it's just has more of these green phrases associated with it.) Part of the reason for more occurrences of abuse phrases in BrE is that UK has more policing of verbal actions than the US does—historically in more restrictive libel laws and more recently in greater use of hate-speech laws and anti-social behavio(u)r orders. (In the US, such laws are more apt to be challenged on constitutional grounds due to the First Amendment right of free speech.) So, verbal abuse is going to make it into the news more.

But back to racial and related words: What pushed me to think about the matter again was this tweet from a fellow American linguist in Britain.

This is not the academic analysis that Lauren was looking for, but just more reflection on the differences in how race (in the 'type of people' sense) and words derived from it (racial, racist) are used and interpreted.

There's little that's more culture-dependent than our notions of how many and which races there are among humans and who can belong to which one. And what counts as a race differs a lot depending on why one's asking. The US Census's list of races you can choose from is a strange mix of colo(u)rs, ethnicities, nationalities at different levels of specificity. If all your grandparents came from Tokyo, your race is a nationality, but if they were ethnic Germans, your race is a colo(u)r.

Hispanic/Latino/Spanish origin in this case is not counted as a race, but as an ethnic or linguistic group, and people are expected to have a race as well as status as Hispanic/Latinx/Spanish "origin".

But when it comes to talking about racism in America, it's not uncommon for people to talk about racism against Hispanic/Latinx people (on the basis of their membership of that group, not another "racial" group). You can see, for example anti-Latino racism in the US column of line 16 here:

Look at the dark blue boxes in the GB column, and you see the kind of thing Lauren was alluding to in her tweet: line 3: anti-Muslim racism and line 6, anti-Jewish racism (and later on in the list, smaller numbers of anti-Semitic racism and anti-Islamic racism) are found in much greater numbers in UK than in US. (The US anti-Arab examples were mostly from one source, so I'm not going to make much of Arab being a 'national/ethnic' alternative to the 'religious' British phrasings.) The Irish column is interesting too--where Irish and Welsh are treated as "races" in the British "racism" context--but perhaps not other British contexts. (Though I just checked and there are 74 hits for "the Irish race" in the Ireland data.) (The "immigrant" numbers there are interesting, but that's the word I talk about in The Prodigal Tongue, so I won't repeat myself here.)

Both US and UK have plenty of hits for "the Jewish race" (a phrase used much historically, so not surprising), but none for "the Muslim race" or "the Islamic race". So, in that case it looks like you can be subjected to racism without being a race. Here's a great example of it in a recent (well, recent when I re-started this post) tweet:

https://twitter.com/novaramedia/status/1029403495882022913

Now, religion is not part of the legal definition of race in terms of most UK discrimination law (but religion may well be another category of discrimination in other laws). The Citizens Advice Bureau advises that you may have a case of racial discrimination if you belong to or are perceived to belong to a category under this definition of race:

Muslims are only 1.1% of the US population. Civil rights movements to do with 'race' in the US have concerned much bigger populations: over 12% of the population are Black/African-American and 17% Hispanic/Latinx (more than half of whom ticked 'white' on their census forms). It's not that religion and race are unconnected in the US. The Ku Klux Klan famously has it in for Jews and (historically, at least) Catholics as well as African-Americans. But perhaps since racism in the US has such deep roots and affects so much of the population, it's harder for that word to be extended to other kinds of discrimination.

There may also be something to the idea that religious discrimination is more of its own category in the US, where religion is much more widely and variably practi{c/s}ed. The country was founded on the principle of religious freedom, but not on any principle of racial equality. That said, it's kind of surprising we don't have a widely used single word for religious discrimination, like religionism or faithism. But we don't seem to.

The moral of the story is: races are different in different cultures because (a) those cultures have different histories involving different peoples, and (b) the categori{s/z}ation of people is made up to serve (the power-holders in) those cultures. If you're interested in these kinds of things, I talk about some of them in chapter 7 of The Prodigal Tongue, but also I've written a few blog posts here about race and ethnicity.

But one thing I did find was that one hears the word abuse in such contexts a lot more in the UK. In the green you can see which adjective+abuse combinations are particularly American (left column) and particularly British (right). (Pink means the opposite—much more typical of the other country.)

|

| Click picture to enlarge. |

But back to racial and related words: What pushed me to think about the matter again was this tweet from a fellow American linguist in Britain.

I’m looking for an academic ref for the fact that when a white British person talks about something being "racist" sometimes they're talking about culture (religion, etc.), not race. I see this use all the time discursively but am struggling to find an analysis! Thanks Twitter 🤓— Lauren Hall-Lew (@dialect) 3 August 2018

This is not the academic analysis that Lauren was looking for, but just more reflection on the differences in how race (in the 'type of people' sense) and words derived from it (racial, racist) are used and interpreted.

There's little that's more culture-dependent than our notions of how many and which races there are among humans and who can belong to which one. And what counts as a race differs a lot depending on why one's asking. The US Census's list of races you can choose from is a strange mix of colo(u)rs, ethnicities, nationalities at different levels of specificity. If all your grandparents came from Tokyo, your race is a nationality, but if they were ethnic Germans, your race is a colo(u)r.

|

| From https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/2010questionnaire.pdf |

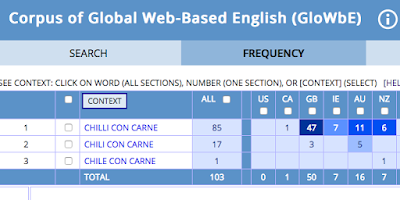

But when it comes to talking about racism in America, it's not uncommon for people to talk about racism against Hispanic/Latinx people (on the basis of their membership of that group, not another "racial" group). You can see, for example anti-Latino racism in the US column of line 16 here:

|

| click to enlarge |

Look at the dark blue boxes in the GB column, and you see the kind of thing Lauren was alluding to in her tweet: line 3: anti-Muslim racism and line 6, anti-Jewish racism (and later on in the list, smaller numbers of anti-Semitic racism and anti-Islamic racism) are found in much greater numbers in UK than in US. (The US anti-Arab examples were mostly from one source, so I'm not going to make much of Arab being a 'national/ethnic' alternative to the 'religious' British phrasings.) The Irish column is interesting too--where Irish and Welsh are treated as "races" in the British "racism" context--but perhaps not other British contexts. (Though I just checked and there are 74 hits for "the Irish race" in the Ireland data.) (The "immigrant" numbers there are interesting, but that's the word I talk about in The Prodigal Tongue, so I won't repeat myself here.)

Both US and UK have plenty of hits for "the Jewish race" (a phrase used much historically, so not surprising), but none for "the Muslim race" or "the Islamic race". So, in that case it looks like you can be subjected to racism without being a race. Here's a great example of it in a recent (well, recent when I re-started this post) tweet:

And again? It’s not a jibe, a jape, a nudge and wink, a jolly, a witticism, a hoot or harmless fun.— Rachel Clarke (@doctor_oxford) 7 August 2018

This is racism.

Islamophobia, to be precise.

So what on earth are you doing normalising this man’s hateful spewings, @bbcnews?

Words matter. https://t.co/Dltu9DcA9R

https://twitter.com/novaramedia/status/1029403495882022913

Now, religion is not part of the legal definition of race in terms of most UK discrimination law (but religion may well be another category of discrimination in other laws). The Citizens Advice Bureau advises that you may have a case of racial discrimination if you belong to or are perceived to belong to a category under this definition of race:

Muslims make up less than 5% of the British population, but are the largest non-Christian religion. Islam mainly came to the UK through immigration from South Asia; about 6% of the population identifies as of South Asian descent (the largest 'racial' minority in Britain). Many British South Asians will have other religious backgrounds, but there about three times as many Muslims as Hindus in the UK, and about 6 times as many Muslims as Sikhs. So, while not all British Muslims are South Asian and not all British South Asians are Muslim, there may be a strong association between being Muslim and being part of a particular ethnic group. Maybe that's why the connection between Islamophobia and racial abuse seems so easy to make in the UK. And perhaps this follows on from the sectarian divisions within and between Britain and Ireland, where discrimination was (and is) not on the basis of skin colour but on the basis of tribalism defined by religion and ethnicity—and where, as we've seen, people do talk about belonging and discrimination in racial terms.What is ‘race’? Race means being part of a group of people who are identified by their race, colour, nationality, citizenship, or ethnic or national origins.

Muslims are only 1.1% of the US population. Civil rights movements to do with 'race' in the US have concerned much bigger populations: over 12% of the population are Black/African-American and 17% Hispanic/Latinx (more than half of whom ticked 'white' on their census forms). It's not that religion and race are unconnected in the US. The Ku Klux Klan famously has it in for Jews and (historically, at least) Catholics as well as African-Americans. But perhaps since racism in the US has such deep roots and affects so much of the population, it's harder for that word to be extended to other kinds of discrimination.

There may also be something to the idea that religious discrimination is more of its own category in the US, where religion is much more widely and variably practi{c/s}ed. The country was founded on the principle of religious freedom, but not on any principle of racial equality. That said, it's kind of surprising we don't have a widely used single word for religious discrimination, like religionism or faithism. But we don't seem to.

The moral of the story is: races are different in different cultures because (a) those cultures have different histories involving different peoples, and (b) the categori{s/z}ation of people is made up to serve (the power-holders in) those cultures. If you're interested in these kinds of things, I talk about some of them in chapter 7 of The Prodigal Tongue, but also I've written a few blog posts here about race and ethnicity.