John Wells recently asked me if he was right in thinking "that BrE consistently uses transfer and AmE decal for the same thing". That's the kind of question that is perhaps best answered with a rh etorical question: Is any English vocabulary used consistently?

etorical question: Is any English vocabulary used consistently?

We're talking about ways of putting images onto other things. In that semantic area, I have both the words transfer and decal in my AmE vocabulary, so I was tempted to say "No, decal means something different from transfer in AmE." But then I thought I should find out if that's just me. It's not just me. But it is complicated.

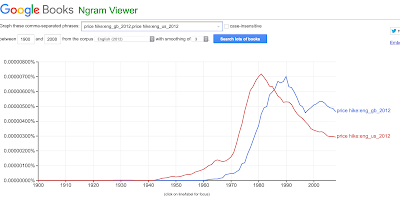

The word decal is definitely more AmE than BrE.

|

| GloWBE corpus |

But what are decals? Some possibilities:

1. Images that can be ironed on to fabrics. E.g. on (orig. AmE) t-shirts or (orig. AmE) tote bags.

2. Images on paper that can be transferred to other things when wet.

- This was what John was thinking of—he recalled ones from his youth for decorating skin. These days, in both AmE and BrE, those are often called temporary tattoos. But decal in this sense is not limited to the skin ones. They might be images that are put onto, say, model airplanes, as in the top right photo here, from a how-to video.

3. Images on vinyl (or similar material) that have sticky material on the image side, so that they can be stuck onto glass (or similar) and show through. The companies I can find that sell them seem to call them reverse-cut vinyl [stickers/transfers/decals].

|

| Image from diginate.com |

4. Vinyl or other high-quality stickers of any sort, intended for use on glass, vehicles, etc. I.e. not just the reverse-cut type, but anything of the type you'd stick onto a car window, say.

- In this case, we can see a phenomenon called lexical blocking. Bumper stickers should be counted under this definition as decals, but since we have a special term for bumper stickers, i.e. (orig. & mainly AmE) bumper sticker, we don't tend to call them anything else. The vinyl stickers on cars that are called decals are different enough from typical bumper stickers (in size, shape, or placement) that they don't meet the criteria for that term.

In my idiolect, decal can be any one of types 2–4, but not the iron-on type. I would call those iron-ons or iron-on transfers. But when I looked up decal in dictionaries, I found the iron-on type potentially included in some definitions, like this one from Collins COBUILD, which gives transfer as the BrE equivalent.

Other dictionaries, like Merriam-Webster and Cambridge, limit decal to types of stickers and don't mention heat-transfer, so more like how I use it.

But then I started asking my American friends—all from my generation, but different parts of the country—what they called the things they might iron onto a t-shirt, and one (she's originally from Kansas, but has more time in Wisconsin/Illinois) immediately offered decal. The others, generally from more eastern parts of the country, said iron-on or iron-on transfer or just transfer.

And so I did a Twitter poll. The problem with polls is that you usually only want to hear from some people, but other people will want to do the poll. I don't know if those other poll-takers care that I throw away their data, but I do know that I have to give them the chance to give it to me because otherwise they pretend they're part of the target group and will thereby mess up my numbers. But after a bit of math(s), we can see (a) that Americans are fairly split on whether iron-ons are included under decal and (b) that my iron-on-excluding usage has slightly more users among my Twitter followers. Keep in mind that my followers may skew older (it's Twitter) and eastward (because of time zone issues).

This all provides more fuel for the idea that we shouldn't talk about what "the American" or "the British" term for something is. (Though I'm sure you'll catch me doing that sometimes.) There's a lot of variation in both, so it's better to think of most expressions as representing an American or a British way of saying things.

Because of the limitations of Twitter polls, I could only ask about one facet of the word's potential meaning: whether or not iron-ons are included. Some followers responded with more specific meanings for decal than I have, for example, one said that he'd only use decal for type 2, in model-making.

For transfer, it's clearly an exaggeration to call it 'British-only' in all of the senses, since Americans do seem to use it for (at least) sense 1. Yet that's what some dictionaries do.

I am tempted to say that transfers have a reverse-print image that is pressed onto a surface, whether that be skin, fabric, glass, etc. (so uses 1-3 above). But there are enough companies out there selling non-reverse-print "vinyl transfers" that reverse-ness is not at this point a necessary condition for many people's understanding of transfer.

To sum up:

- Decal is a fairly American word, but Americans vary in how they define/use it.

- Transfer as a noun for a type of image printing/attaching occurs in British English, but is also available in AmE, especially for the iron-on type.

PS: there is variation in how decal is pronounced in AmE, particularly which syllable gets the stress. You can hear more on YouGlish. In my experience, it's more common to put the stress on the first syllable. Thanks to Adonis in the comments for raising this.