First, we can see that one of a kind has been increasing fairly steadily in both AmE and BrE, but it's definitely more American. One-off's appearance on the American scene has not caused one of a kind to become less frequent.

|

|

|

|

|

I listen to a lot of podcasts, and I notice things. One thing I’ve noticed is that no one seems to be able to agree with anyone else without saying 100%. That cliché seems to have caught on in both UK and US, so that’s not the topic of this blog post. This blog post is about another thing I’ve noticed: an apparent change in the British pronunciation of analogous.

Dictionaries give the pronunciation as /əˈnaləɡəs/ (or similar; all dictionary pronunciations here from the OED). That is to say, the stress is on the second syllable and the ‘g’ is pronounced ‘hard’ as in analog(ue). What I’ve been noticing in BrE speakers is a non-dictionary pronunciation, /əˈnaləʤəs/, which is to say with a ‘soft g’ as in analogy.

To see how common this pronunciation is, I looked to YouGlish, which finds a word in YouTube videos (using the automatic transcription), classifies them by country, and presents them so that you can listen to that word pronounced by lots of people in lots of contexts. The automati{s/z}ation means that it makes mistakes. I wanted to listen to the first ten pronunciations in US and UK, but had to listen to 12 in the ‘UK’ category to get ten that were both British and the right word.

|

| screenshot from examplesof.net |

The first British one had a pronunciation that I hadn’t heard before: /əˈnaləɡjuəs/, as if the spelling were analoguous. Half (five) of the British ten had the hard ‘g’ pronunciation, four had the soft-g pronunciation I’d been hearing, as if the spelling is analogious (or analogeous). All of the first 10 US ones said /əˈnaləɡəs/.

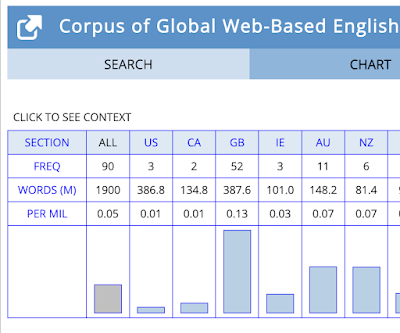

The word analogous seems to be more common in AmE. There are 2433 examples of it on US YouGlish, versus 147 examples tagged-as-UK. (The US population is about five times larger than UK’s, and Americans might post videos to YouTube at a higher rate than Britons. So while that’s a very big numerical difference, it doesn’t mean Americans say it16 times more than the British.) That’s in speech. In writing, there’s about twice as much American analogous in the News on the Web corpus:

So, Americans have presumably heard the word more than Britons have, leading to a more uniform pronunciation.

Now, when people know a word more from reading it than from hearing it, we might expect that they will rely on the spelling to know how it sounds. What’s a bit odd here is that the non-dictionary pronunciations contradict the spelling. Perhaps some people who know the word from print have not fully noticed that the spelling is -gous and think it’s -gious. Or perhaps they’re deriving the word anew from their knowledge of other members of that word-family.

Analog(ue) = /ˈanəl*ɡ/ + -ous = analogous /əˈnaləɡəs/ [dictionary]

(* different vowels: AmE [ɔ] or [ɑ] & BrE [ɒ])

Analogy = /əˈn*lədʒi/ + -ous = analogious > /əˈnaləʤəs/ [non-dictionary]

(* different vowels: AmE [æ] & BrE [a])

Analogu(e) + /ˈanəl*ɡ/ + ous = analoguous > /əˈnaləɡjuəs/ [non-dictionary]

In the last case, the ‘u’ that is silent in analogue is treated as if it’s ‘really there’ and pronounced in the extended form. This sometimes happens with ‘silent’ final consonants and suffixes. Think of how the ‘silent n’ in damn and autumn are pronounced in damnation and autumnal. This is a bit different, since it’s a vowel, and I can’t think of another example where a silent final ue does the same thing. We don’t go from critique to critiqual (it’s critical) and tonguelet is not pronounced tun-gu-let or tung-u-let: the u remains silent.

When I tweeted (or skeeted or something) about the soft-g analogous pronunciation, some respondents supposed that the -gous ending is not found in other words, and therefore unfamiliar. (One said they could only think of humongous, which seems like a jokey word). It is true that analogous is the most common -gous word, but the OED lists 153 others, most of them fairly technical terms like homologous, tautologous, homozygous, and polyphagous. There are fewer -gious words (83), but they’re much more common words: religious, prestigious, contagious, etc. The relative frequency of -gious endings versus -gous endings may have contagiously spread to analogous.

But there’s something to notice about contagious and its -gious kin and analogous and its -gous mates. The main stress in a word like contagious is in the syllable just before the -gious, i.e. the penultimate syllable (/kənˈteɪdʒəs/, religious = /rᵻˈlɪdʒəs/, prestigious = BrE /prɛˈstɪdʒəs/ and AmE /prɛˈstidʒəs/ ). (English stress patterns are often best described by counting syllables from the back of the word.) The main stress in analogous is not on the penultimate syllable, but on the one before (the antepenult). That is, we say aNAlogous not anaLOgous, no matter how we pronounce the ‘g’. If soft-g analogous was surmised from (mis)reading rather than hearing the word, and if it was following the model of words like contagious, we’d expect it to be pronounced anaLOdʒous, with some sort of O sound as a stressed vowel. That's not what's happening.

(One way to think of this is that there’s a general pattern that long -ous words are stressed on the antepenultimate syllable, but only if we think of the ‘i’ in -gious words as a syllable of its own, which gets elided after the stress pattern has been set. There’s way more to explain about that than I can do in a blog post…and I am relying on decades-old phonology education here.)

Now, I am not a phonologist or a morphologist, so I asked my former colleague and friend Max Wheeler to check my reasoning here. He's OK'd it and adds:

To make your argument another way, while -gous is unusual, '-jous' after an unstressed vowel is unparalleled.[...] analogy is quite a common word, while analogous is much rarer (and people may not readily connect semantically to analog(ue)). Even people with a literary education are unfamiliar with the /g/ - /j/ alternation, so 'mispronounce' fungi, pedagogy, as well as analogous, taking no guidance from the spelling. The phoneme from the more frequent word-form wins.

The moral of the story: soft-g analogous is a bit weird—which is to say, a bit interesting.

If you liked this post, you might like:

High school graduation parties are generally not held in England—partly because there one does not graduate from high school. Graduation is only for those who get a degree from a university. But even when people graduate with a degree, family parties like this are not common. Generally, Americans do a lot more of this kind of party-throwing and gift-giving to mark life transitions (and help out a bit). See the earlier post about showers.

Meanwhile, my 16-year-old (aka Grover) has recently finished secondary school in England. (Her secondary school, as it happens and unusually for England, has high school in its name.) Before school finished, she took 27 exams over 6 weeks in 9 subjects—this is what's known as the GCSEs (General Certificate[s] of Secondary Education). (NB: Many of the educational issues that come up here have been described in previous blog posts—rather than clicking on each link here, you might want to save your efforts for the 'related posts' links below.) Grover won't know her results in those exams till late August, when she'll be able to enrol(l) in the sixth-form college that's accepted her. (Though she's accepted to the college, she won't know until she has her exam results whether she's met the prerequisites for the A-level subjects she's chosen.)

Her status has been difficult to explain to her American family. Sixth-form college is not what Americans think of as college, which would be called university in BrE. In England, sixth-form (and many other diverse things!) counts as further education—after secondary school, but not degree-level study. In an effort to translate her status, she's started telling Americans that she's graduated. Her reasoning for this is that (a) they had a little ceremony in an assembly on their last day of school, (b) she's going to something called college, and (c) she's had a prom (an imitation of the American tradition for these younger students). But since she doesn't even know whether she's passed her exams,* it can't really be counted as "graduating", can it? I have suggested to her that she may be misrepresenting her situation. She doesn't mind. It might yet pay off...

What she is, in Britain, is a school leaver. Instead of getting a mortar board and gown, she got a (orig. BrE) hoodie. (Pic here from an Etsy shop. Grover's hoodie is back in Brighton.)

*Oh, I'm sure she's passed. Whether she's got the prerequisite grades is another matter, so it's all a bit stressful.

So, I want to say: Congratulations to our BA English Language and Linguistics and BA English Language and Literature graduates of 2024! Here's the outfit you didn't get to see me wear.

Related posts:

Types of schools and school years

(the one that's linked-to a LOT above!)

I've just found a bunch of research on my computer about conflab. I can't remember why I saved a bunch of corpus results on it, but maybe it was season/series 5 of Succession that brought it to my attention, when an Australian actress playing an Anglo-American rich person said it in dialog(ue) written by a rather British writing team:

I knew the word confab, a shortening of confabulation, and I'm pretty sure I'd heard conflab before and dismissed it as a speech error. This time, I did the responsible thing and looked it up. It's not a speech error.

Confabulation came into English in the 15th century from Latin, meaning 'a conversation'. (In the 20th century, it acquired a psychiatric meaning: 'a hallucination of a memory'. That newer meaning is irrelevant to the abbreviated forms I'm discussing here.) A confab is a conversation, an argument, or (in a later development) a conference or the like. It's an informal word, as clippings often are, and sounds a bit jokey—but it's surprisingly old. (Surprising to me, at least.) The first OED citation is a British one from 1701. The second is from Thomas Jefferson in 1763, so it was not unknown in America back then. Green's Dictionary of Slang has a few more British examples from the 18th century:

|

I remember (early in my time in England) asking an English friend what she meant when she said she looked forward to a bit of stodge. She meant 'a carbohydrate-heavy meal'. It was new to me, and this chart from the Corpus of Global Web-Based English (GloWbE) lets you know why: most Americans don't talk about stodge:

|

| stodge in the GloWbE corpus |

But stodgy is a different matter:

|

| stodgy in the GloWbE corpus |

So how could I not figure out from context what stodge meant, if stodgy be a relatively common word in AmE?

Because Americans typically don't use stodgy to mean 'carb-heavy'. We mostly use it to refer to someone or something that is so conventional or inactive as to be dull. You can see this in the typical nouns following stodgy in the News on the Web corpus. Here are the top 3:

| BrE | AmE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | stodgy food | stodgy industry |

| 2 | stodgy performance | stodgy incumbents |

| 3 | stodgy comfort food | stodgy reputation |

Stodgy performance (in sport[s]) in the BrE column shows that it can also mean 'dull' in the UK. It's a negative thing when it comes to things other than food, and it can be negative regarding food too. You might feel unpleasantly heavy after eating stodgy food. But stodgy food can also be nice, as I know all too well.

I reali{s/z}e I haven't given any AmE equivalents. That's because I felt like these words filled a gap in my vocabulary when I learned them. But if any Americans out there have some good words for these things, do let us know in the comments!

P.S. See the comments re the original 'muddy' sense of claggy. It's also made an appearance in the NYT Spelling Bee: an archive of disallowed BrE words post.

P.P.S. I dealt with this a bit more in my newsletter, including a less-used synonym of claggy, clatty. Related, there is also clarty ('smeared/covered with sticky mud'), which didn't make it into the newsletter, but is discussed in the comments below.

Inspired by Anatoly Liberman's Take My Word for It: A Dictionary of English Idioms (which I've reviewed for the International Journal of Lexicography), here's a quick dip into some ways of saying one's going to bed, where they've come from and who uses them now.

|

| From Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein (via Bad Robot) |