A retired colleague contacted me with this query:

I hear plenty of COVID-19 from US sources, so that didn't strike me as quite right, but I had a look (on 29 April) at the News on the Web (NOW) corpus, which (so far this year) had 226 covi* (i.e. words starting with covi-) per million words in US and 49 per million in UK. For coronav* it's 362 US v 92 UK. (I searched that way so that I'd get all variations, including COVID without the -19, without the hyphen, coronaviruses, etc.).

In an initialism, you pronounce the names of the letters: the WHO stands for World Health Organization and it is pronounced W-H-O and not "who". It's spel{led/t} with all caps (or small caps), no matter where you live. (AmE styles are more likely than BrE styles to insist on (BrE) full stops/(AmE) periods in these: W.H.O.—but styles do vary.)

Acronyms use the initial letters of words to make a new word, pronounced as a word. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's short name is pronounced "nasa", making it a true acronym. All AmE styles that I know of spell it with caps: NASA. Many BrE styles spell it like any other proper name, with just an initial capital: Nasa.

This disease name provides a slightly different case because it's doesn't just use initial letters: COronaVIrusDisease. That's probably why I'm seeing some initial-only Covid in AmE, for instance in the Chronicle of Higher Education, where they spell other acronyms (like NASA) in all caps.

Other variants, like CoViD and covid are out there—but they are in the minority. COVID and Covid rule.While some other UK sources, like the Guardian, follow the initial-cap style (Covid), many UK sources use the all-cap style, including the National Health Service and the UK government.

And on that note, I hope you and yours are safe.

P.S. Since I'm talking about newspaper uses, I haven't considered pronunciation—but that discussion is happening in the comments.

Has a dialect difference emerged between US novel coronavirus/new coronavirus and UK COVID-19, do you think? Novel coronavirus/new coronavirus is favoured by Reuters, but I don't know whether that counts in the dialect balance.

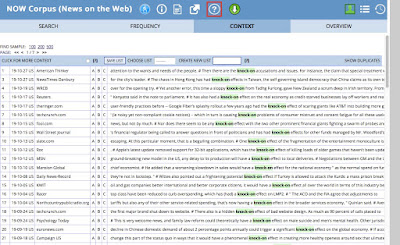

I hear plenty of COVID-19 from US sources, so that didn't strike me as quite right, but I had a look (on 29 April) at the News on the Web (NOW) corpus, which (so far this year) had 226 covi* (i.e. words starting with covi-) per million words in US and 49 per million in UK. For coronav* it's 362 US v 92 UK. (I searched that way so that I'd get all variations, including COVID without the -19, without the hyphen, coronaviruses, etc.).

Now, I don't trust the geographical coding on the NOW corpus very

much, because you have things like the Guardian showing up in the US

data because it has a US portal that has US-particular content, but also

all the UK content—and that doesn't do us much good in sorting out AmE from BrE. I really don't know why the

per-million numbers are so much higher in the US sources, since the news in both places is completely taken over by the virus and stories related to it. But anyway, about 38% of the (named) mentions of the disease are COVID in the US and 35% in the UK, so there is no notable difference in preference for COVID. I found it interesting that the two newspaper apps on my phone (Guardian [UK] and New York Times) prefer coronavirus in headlines, even though COVID-19 is shorter.

But my colleague is right that there is a lot more new/novel coronavirus in US than UK. About 12% of AmE usages are prefaced by an adjective that starts with N, while only about 3% of BrE coronaviruses are. Distribution is fairly even between novel (from medical usage) and new. It's worth noting that since I'm only searching news media, new/novel is probably far more common in this dataset than it would be in everyday interactions.

But my colleague is right that there is a lot more new/novel coronavirus in US than UK. About 12% of AmE usages are prefaced by an adjective that starts with N, while only about 3% of BrE coronaviruses are. Distribution is fairly even between novel (from medical usage) and new. It's worth noting that since I'm only searching news media, new/novel is probably far more common in this dataset than it would be in everyday interactions.

Including the definite article (the coronavirus) seems to be more common in AmE. If I just look for how many coronavirus occurrences are preceded by the, the proportion is 45% for AmE and 37% for BrE. this search hits examples like the one in the 'middle school' story on the left: the coronavirus lockdown where the the really relates to the lockdown. So, to try to avoid this problem, I searched for (the) coronavirus [VERB] and (the) coronavirus [full stop/period]. In those cases, then AmE news media have the the about 50% of the time, while BrE ones have it less than 30% of the time. That misses the new/novel coronavirus (because of the adjective between the and coronavirus), so the real difference in the before coronavirus is probably more stark.

But my colleague is right that there is a lot more new/novel coronavirus in US than UK. About 12% of AmE usages are prefaced by an adjective that starts with N, while only about 3% of BrE coronaviruses are. Distribution is fairly even between novel (from medical usage) and new. It's worth noting that since I'm only searching news media, new/novel is probably far more common in this dataset than it would be in everyday interactions.

But my colleague is right that there is a lot more new/novel coronavirus in US than UK. About 12% of AmE usages are prefaced by an adjective that starts with N, while only about 3% of BrE coronaviruses are. Distribution is fairly even between novel (from medical usage) and new. It's worth noting that since I'm only searching news media, new/novel is probably far more common in this dataset than it would be in everyday interactions.Including the definite article (the coronavirus) seems to be more common in AmE. If I just look for how many coronavirus occurrences are preceded by the, the proportion is 45% for AmE and 37% for BrE. this search hits examples like the one in the 'middle school' story on the left: the coronavirus lockdown where the the really relates to the lockdown. So, to try to avoid this problem, I searched for (the) coronavirus [VERB] and (the) coronavirus [full stop/period]. In those cases, then AmE news media have the the about 50% of the time, while BrE ones have it less than 30% of the time. That misses the new/novel coronavirus (because of the adjective between the and coronavirus), so the real difference in the before coronavirus is probably more stark.

The media's style guides are supposed to guide the choices journalists and editors make in phrasing such things, but how strictly they follow their own guides is another matter. I had a look at a couple:

The Guardian Style Guide (UK) says:

coronavirus outbreak 2019-20

The virus is officially called Sars-CoV-2 and this causes the disease Covid-19. However, for ease of communication we are following the same practice as the WHO and using Covid-19 to refer to both the virus and the disease in our general reporting. It can also continue to be referred to as the coronavirus. [I've added the bold on the latter]

The Associated Press (US) gives similar advice, though it goes into more particular rules for science stories.

As of March 2020, referring to simply the coronavirus is acceptable on first reference in stories about COVID-19. While the phrasing incorrectly implies there is only one coronavirus, it is clear in this context. Also acceptable on first reference: the new coronavirus; the new virus; COVID-19.

In stories, do not refer simply to coronavirus without the article the. Not: She is concerned about coronavirus. Omitting the is acceptable in headlines and in uses such as: He said coronavirus concerns are increasing.

In comparing the two passages you can see one predictable difference between them. AP writes COVID in all caps, Guardian has Covid with the initial capital only. There is a widespread preference in BrE (and generally not in AmE) to differentiate between initalisms and true acronyms. (There's been a bit in the Guardian about it, here.)Passages and stories focusing on the science of the disease require sharper distinctions.COVID-19, which stands for coronavirus disease 2019, is caused by a virus named SARS-CoV-2. When referring specifically to the virus, the COVID-19 virus and the virus that causes COVID-19 are acceptable. But, because COVID-19 is the name of the disease, not the virus, it is not accurate to write a new virus called COVID-19. [bold added]

In an initialism, you pronounce the names of the letters: the WHO stands for World Health Organization and it is pronounced W-H-O and not "who". It's spel{led/t} with all caps (or small caps), no matter where you live. (AmE styles are more likely than BrE styles to insist on (BrE) full stops/(AmE) periods in these: W.H.O.—but styles do vary.)

Acronyms use the initial letters of words to make a new word, pronounced as a word. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's short name is pronounced "nasa", making it a true acronym. All AmE styles that I know of spell it with caps: NASA. Many BrE styles spell it like any other proper name, with just an initial capital: Nasa.

This disease name provides a slightly different case because it's doesn't just use initial letters: COronaVIrusDisease. That's probably why I'm seeing some initial-only Covid in AmE, for instance in the Chronicle of Higher Education, where they spell other acronyms (like NASA) in all caps.

Other variants, like CoViD and covid are out there—but they are in the minority. COVID and Covid rule.While some other UK sources, like the Guardian, follow the initial-cap style (Covid), many UK sources use the all-cap style, including the National Health Service and the UK government.

And on that note, I hope you and yours are safe.

P.S. Since I'm talking about newspaper uses, I haven't considered pronunciation—but that discussion is happening in the comments.