flapjacks and pancakes

I cannot believe I've never written a post about the word flapjack. So here it is.

In AmE, flapjack is a synonym for pancake, as is hotcake. Hey, it's a big country. We're allowed to have lots of words for things.

Here in the south of England (at least), those things are often called American pancakes to differentiate them from the more crêpe-like English pancakes (often eaten with lemon juice and sugar). Then there are Scotch pancakes, also called drop scones, which are very much like American pancakes. I've seen one site that claims that Scotch pancakes have sugar in them but American pancakes have butter in them, and I can tell you that my American pancakes have a little sugar and no butter (but some cooking oil) in them, so I'm not believing that website. I'd say the main difference between Scotch pancakes and American ones is the size, with Scotch pancakes being closer to what are called silver dollar pancakes in AmE, which can have a similar circumference to a crumpet or (English) muffin—that is to say bigger than a silver dollar. (All links in this paragraph are to recipes.)

A few immigrant pancake notes:

- I was really surprised (when I arrived 22 years ago) to find that in the UK one can buy cold Scotch pancakes in a UK supermarket. I'd never seen such a thing in the US. Maybe frozen ones for heating up, but not pancakes in the bread aisle of the supermarket. Even more surprised when I first saw someone eating them cold, straight out of the (more BrE) packet.

- If you order "American pancakes" in England they (a) generally won't come with butter (what's the point?!) and (b) will be covered with so much sweet stuff that you will get a cavity before you've swallowed the last bite. At least around here, the pancakes themselves are pretty sweet, then they tend to put the maple syrup on before they serve it AND dust them with a ton of (AmE) confectioner's sugar /(BrE) icing sugar. I have mostly learned better than to order them, but my child hasn't.

- These days, with American pancakes being much more common in Brighton, the actual pancakes can be pretty good (though, as I say, often too much sugar in the batter). When I first moved here and only a handful of places served them, they were invariably undercooked in the middle. I assume this was because the cooks had been trained in English pancakes and couldn't believe a pancake could take so long to cook. The best ones in Brighton are now made by my English spouse, who's taken every food I've ever cooked for him and made it his mission to master it.

|

| BBC Good Food Easy Honey Flapjacks |

flour

I'm just going to do it as a list:

| BrE | AmE |

|---|---|

| plain flour | all-purpose flour |

| strong (bread) flour | bread flour |

| wholemeal | whole wheat |

| [no such thing] | cake flour |

| corn flour | cornstarch |

| corn/maize meal | corn flour, corn meal |

| self-raising flour* | self-rising flour* |

| [no such thing] | Wondra (instant flour) |

| 00 flour | fine flour |

*Postscript from 2020: @BNW informs me that self-raising and self-rising differ a bit: "It seems like the AE self-rising flour has less baking powder, added salt, and a slightly softer/lower-protein flour.". So substitute with caution.

|

| Photo: Veganbaking.net - CC BY-SA 2.0, Link |

AmE uses pastry flour more than BrE does. Sometimes in BrE that would be 00 flour--but 00 flour can also be more yellowy pasta flour. (I think I may have heard patisserie flour on Great British Bake-Off, but I'm not finding much evidence of it elsewhere.)

If you follow the link at Wondra above, you'll see it's a special kind of flour that's mostly used for making gravies and sauces. One thing to say about British gravies: they are usually considerably less thickened than typical American gravies.

For more on flour and flour (the word), here's a nice international overview.

Finally, this isn't a bread post, but I must note a flour-related bread difference. Order breakfast in the UK, and you will (probably) be asked: white or brown? in reference to your toast. In the US, you'd be asked white or wheat? (Actually, in both countries you may be given more options. But I"m saving those for a bread post.)

If you ever want a reason to argue that British English is superior, do skip the reasons I've already debunked (maths, herb, etc.) and go with this one. Calling one bread-made-of-wheat wheat in contrast to another bread-made-of-wheat is a bit silly. And chances are: you'll say wheat, they'll hear white and breakfast will be ruined!

Postscript (30 Jan): I've added AmE corn flour (=BrE corn meal or maize meal) to the list. Americans use this to make corn bread and corn muffins (a kind of quick bread). Whenever I make these for my English family, I get to eat the whole batch because they do not appreciate its wonderfulness. The UK increasingly has polenta cakes of various types, offered as gluten-free options. Those are like the consistency of corn bread (a bit less crumbly) but more aggressively sweetened, in my experience, by being drenched in a fruit syrup.

---------

Some notes from the harmless drudge:

As the deadline for my book approaches AND I go back to teaching after a glorious year of writing said book (thanks NEH!!!), you can probably expect that I'll be doing a bit less posting than in 2016. I'll set aside a bit of time per week, but less time than it usually takes me to write a post. So, either they'll be very short posts or a few weeks apart. (Though as I viciously cut [more BrE] bits out of the book, maybe they'll end up as quick posts here.)

I will be on (orig. AmE) radios a bit this spring (UK and NZ plans at the moment). I'll announce these via Twitter and Facebook, as usual, and I'm also noting forthcoming "appearances" on the Events and Media page of the blog. (The radio announcements will go up when broadcast dates are firmer.)

chil(l)i

Hello from the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Linguistics of English, or #ISLE5, as all the cool kids are tweeting it. We have an afternoon for touristic activities, but since we're in London, I'm feeling a combination of (orig AmE) 'been there, done that' and 'I could do that any time'. What's not available any time is a bit of quiet to blog. So, yay for everyone else going to Samuel Johnson's House (been there, got the postcards) and for my lovely hotel lounge and wifi. Today's post was started possibly years ago (I've lost track), when Lauren Ackerman asked me about British chilli versus American chili.

Hello from the Fifth Conference of the International Society for the Linguistics of English, or #ISLE5, as all the cool kids are tweeting it. We have an afternoon for touristic activities, but since we're in London, I'm feeling a combination of (orig AmE) 'been there, done that' and 'I could do that any time'. What's not available any time is a bit of quiet to blog. So, yay for everyone else going to Samuel Johnson's House (been there, got the postcards) and for my lovely hotel lounge and wifi. Today's post was started possibly years ago (I've lost track), when Lauren Ackerman asked me about British chilli versus American chili.I went to my usual first stop: the Oxford English Dictionary. And I am sad to say that the entry for this item has not been fully updated since the first edition in 1889—which is to say, look at those spellings! (Not blaming them, just sad for my post that they haven't got(ten) to this one yet!)

Yes, chilli is still the BrE spelling for piquant peppers—but giving chilly as the alternative spelling and not the standard AmE chili reads very odd in the 21st century. Chili is acknowledged there as a historical spelling, and is present in the quotation evidence in the entry. And it's consistently been the more common spelling in the US:

|

| (click to enlarge) |

At the conference, I've been at two sessions where someone's called into question the OED tagline, visible at the top of the dictionary screenshot: 'The definitive record of the English language". That's marketing talk, not lexicographical talk, and it's unfortunate. There can be no definitive record of the English language, because there is no definitive English language. It's always varying and changing and you can never know if you've found the first instance of a word or the last one, etc. So here's a little plea (in the form of advice) to the Oxford University Press: If you put most before definitive it would be an accurate tagline. And it would have a marketing-department-friendly superlative in it! Win-win!

As a side-note, there's this little bit of puzzling prescriptivism in the run-on to the entry (i.e. the additional defined items at the end), which seems to have been added later—or at least I'm assuming so, given the AmE spelling (it's hard to tell, though, the link to the previous edition includes none of the run-ons).

I've been trying to figure out what that 'erron.' is referring to. I believe what it's saying is that the "real" meaning of chili pepper is 'pepper tree' and it's an error to use it to refer to chil(l)is, but why does it only have the US spelling? It's not clear to me when this chili pepper was added to the entry, as the link to the 2nd edition does not include all the compounds that are in the run-on entries. But it must be old, as it's not marked as a post-2nd-edition addition. But it's interesting to see how recent it is to say "chil(l)i pepper":

Anyhow, back to the word itself: it comes ultimately from Nahuatl, with an /l/ sound in the middle. We pronounce it with a 'short i' sound (like in chill). You can see, then why BrE likes the double-L spelling: without a double consonant, it looks like it should have a a different vowel: we say wifi differently than we'd say wiffi; fury versus furry, etc.

So why does AmE have a single L? My educated guess would be because Americans have had more consistent contact with Spanish. When the Spanish went to spell it, they used a single L, because double consonants don't do the same thing in Spanish spelling that they do in English. If you pronounce chilli in Spanish, there's no L sound. (What sound is there depends on your dialect of Spanish, but I learned in my US Spanish classes to pronounce the LL like a 'y' sound.) It stayed Spanish-ish in American, while getting a more English-ish spelling in Britain.

Now, I think that back in the mists of time when Lauren requested a post on chil(l)i, she meant the stew, rather than the fruit. I am not going to wade into the debates about what "real" chil(l)i (con carne) should have. But I will say this: every American I've seen to order the dish in the UK has had a moment of "Whaaaa?" when it was served with rice. Not something we're used to. But nice when you get used to it.

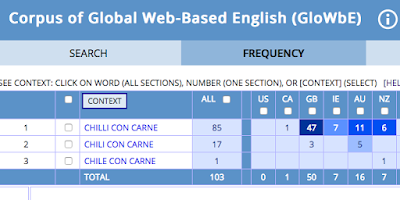

There is another spelling issue here, though. The pepper almost always ends with an i, but the stew sometimes ends with an e. But not much anymore, according to my corpus searches:

And on that note, I'll post this before my battery dies!

pleonasms

Pleonastic expressions are things that language haters like to hate on. (These people often claim to be language lovers, but they don't seem to be very good at the love part.) So, they're the kind of thing that people complain to me about, with the Americans saying "Why do the British say X? It's repetitive and illogical", and the British saying "Why do Americans say Y? It's repetitive and illogical."

At their worst, these complaints come out as "Why do Americans/Brits always add extra words?"

When I get those complaints, I reply with some phrases from the speaker/writer's own dialect that have 'illogically redundant' words (it's not hard to do) and I say something like "language is not logical and it thrives on redundancy".

I mean, why say Yesterday we baked a cake? Yesterday is in the past, so why bother with the past tense marking on the verb? So redundant. Chinese wouldn't put up with that.

Thinking about these accusations that Brits/American always add extra words, I put a call out on Twitter and Facebook for BrE/AmE-specific pleonasms that others have noticed. We can see from the resulting lists below that there are no innocent parties in the Pleonasm Wars. Many of expressions aren't only said in the 'offending' dialect, but they are more common in one than the other. To indicate the relative "Americanness" or "Britishness" of a phrase, I've given a ratio, which indicates the proportion of instances of the phrase in the British and American portions of the Corpus of Global Web-Based English. (The minority uses in the other dialect may be things like "Can you believe the British call beets beetroot?". That is, the fact that there are some in the other dialect doesn't mean it's necessarily really used in that dialect. The ratios help indicate the chances that it really is AmE- or BrE-specific.) I've bolded the bit of the expression that could arguably be left out without a change in meaning and put links to places I've discussed these before, if available.

American expressions that British folk might find pleonastic

irregardless 5:1 (though generally considered non-standard in AmE)

in and of itself 3:1

tuna fish 3:1 (0 BrE instances as closed compound tunafish)

where I( a)m at 2:1 (again, not exactly standard AmE; and the corpus numbers have a lot of 'noise')

(An American one I didn't count was off of because the of is there for grammatical reasons not semantic ones. See the old post for discussion.)

British expressions that American folk might find pleonastic

beetroot 22:1

hosepipe 13:1

in N days' time 10:1

goatee beard 9:1

go and [verb] e.g. go and see = 6:1 versus go see 1:2; note that go+verb predates go and verb in English--the and has been added in BrE, not deleted in AmE

postgraduate 6:1

station stop 4:1

at this moment in time 4:1

chocolate brownies 3:1

late addition (2019): marker pen 24:1

You might want to argue that some of these are not redundant. It is a matter of perception. Brits might say beetroot isn't redundant because it distinguishes that part of the plant from the greens, but beetroot is redundant to Americans in the same way that carrotroot would be. Chocolate brownies is redundant because in AmE if it's not made of chocolate, it has to be called something else (e.g. blondies). (Americans do have the word brownie for other things too, the context is enough to let us know it's a baked good and not a fairy.) It's been argued to me that station stop is not redundant because trains sometimes have to stop (e.g. for a signal) when they're not at a station, and they sometimes pass stations without stopping. Did you know there's a tuna fruit?

In the end, the Twitter and Facebook and email people gave me more British [alleged] pleonasms than American ones. Possible reasons for this:

- Maybe British English does have more of them.

- Maybe my social media posts were at better times for the US than the UK. (My waking hours don't quite fit the UK, in spite of 15 years' residence.)

- Maybe Americans notice British pleonasms more than Britons notice American pleonasms (I was required to buy a copy of Strunk and White at college. I can't imagine the same happening in UK, where writing isn't a required university subject. So, maybe Americans are trained to cut extra things out of language where British folk are not. We're the country most likely to excise extra letters in the spelling system too.)

All my linguistically-correct tolerance for pleonasms aside, I am a ruthless redactor of extra words in academic writing. I train my students in Strunk and White's Rule 13: Omit needless words. If they write

Another reason why the categorisation of chocolate* is significant for humans derives from the fact that humans are essentially and uniquely a ‘languaging’ species.

...they get back the following, with an obnoxious note along the lines of "Your way: 24 words; My way: 11 words. Don't make me read twice as many words as I have to!!":

* The noun has been changed to chocolate in order to protect the author's identity. But chocolate is particularly relevant to humans as a 'languaging' species. Without it, we couldn't have Cathy cartoons.Another reason why the categorisation ofcChocolate*is also particularly relevantsignificantfor humansderives from the fact thathumans are essentially and uniquelyasa ‘languaging’ species.

[i.e. Chocolate*is also particularly relevantfor humans asa ‘languaging’ species]

In writing academic essays for which (a) you have a word limit, so (b) the more words you use, the less you can say, and (c) you can be assured that your reader is going to be tired and grumpy before they even start reading, pithiness rules the day.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to those who contributed pleonasms to the list: Amanda P, Barbara J, Catherine P, David L, Iva, Jennifer, Kim E, Naomi N, Nicole S, Pam T, Rebecca M, Richard H, Sian C, Simon B.

I don't give full names unless I'm given permission to, and I am always happy to link your name to your blog/Twitter/webpage. So, if this applies to you, let me know and I'll add surnames and/or links.

recipe verbs

When I first moved to the UK, I hungrily watched the (orig. AmE) tv in my sublet apartment/flat in an attempt to acculturate myself. I can't remember if it was on an ad(vert) or on an early series of The Naked Chef, but I clearly remember the sentence:

Just bung it under the grill!

I already knew grill (=AmE broiler) from my time in South Africa. It was bung (meaning something like 'put forcibly, carelessly') that struck me. It seemed such an unattractive word, and yet it was being used about some food that was supposed to be wonderful after the bunging. Was this telling me something about British attitudes to food and cooking? Was it supposed to make the dish-making seem so sloppy anyone could do it? The questions clearly stuck in my mind, because the phrase has stayed with me for 25 years.

Bung was the first thing to come to mind when Maryellen Macdonald wrote to me:

You have a long post about cooking word differences, but I don’t think it contains a discussion of “add” vs. “tip”. US recipes say things like “add the carrots” to the pan, whereas UK recipes say “tip in the carrots”. My husband, the better cook in the household, asked me, “What do they mean tip the carrots? They’re cut up!” Hmm, maybe this little observation-ette isn’t quite sufficient for a post, but, perhaps you can use it somewhere.

I'm not sure which cooking-word difference post she was thinking of, since there are LOTS of them. But it made me think about "recipe verbs". Words like bung and tip are not necessarily cooking words—you can bung or tip a lot of things. But they are the kinds of words one finds in recipes or cooking programmes/shows.

I started asking my friends for other recipe-verb differences they had noticed. One friend (thanks, David!) pointed me to this parody cooking series, Posh Nosh, in which Richard E. Grant and Arabella Weir are minor aristocracy with an upscale restaurant brand. This particular nine-minute episode includes many great (fake) cooking verbs, instructing you to interrogate (clean?) then later to thrill open your mussels, to pillage some bones and to "gently gush [some AmE broth/BrE stock] until it completely obsesses the rice."

My friends weren't great at coming up with verb differences. (Several nouns were suggested.) Thank you to Ben, Björn, David, Jason, Michèle, Wendi for their suggestions. To complement these, I ended up doing an Advanced Search in the Oxford English Dictionary for region-marked cooking verbs. This post then got stupidly long and AmE biased; the OED is not good at marking words that are general to British English but not to North American.

For the following, I am marking things as AmE or BrE if either the OED or corpus results fairly firmly put the verb on one side of the Atlantic or the other. But you might know some of the "the other country's" words, especially if you ingest a lot of recipes and cooking programmes/shows. These things have been moving rapidly with mass media.

Some actual cooking verbs

- AmE broil v BrE grill is (part of) the topic one of my first blog posts. Also:

- AmE charbroil = cook over charcoal (not very frequent, more common in the modifier form charbroiled)

- AmE panbroil = cook [meat/fish] in pan with very little fat

- AmE grill v BrE toast comes up in a long post about cheese sandwiches (BrE toasties)

- AmE grill v BrE barbecue comes up in a post from the 4th of July

- orig. AmE nuke & zap: (informal) to microwave

- orig. AmE pot-roast: to slow-cook meat (esp. beef) in a covered pot/dish

- orig. AmE stir-fry (but this has been in BrE for most of your lifetimes)

- AmE plank: From OED: "Originally and chiefly North American. To prepare (meat, fish, etc.) by cooking it on a board over an open fire; (in later use) to cook on a board in an oven"

- AmE shirr: to poach (e.g. an egg) in cream rather than water. (I knew the word, but not what it meant!)

- orig. AmE flip: Not really a recipe verb, but...from the OED:

transitive. Originally and chiefly U.S. To cook (items of food) by turning over on a hotplate, grill, or griddle. Now typically with the implication that the subject has a job in a fast-food restaurant (chiefly in to flip burgers).

Some verbs that are often used to modify food words

- roast v roasted (of potatoes, chickens, etc.)—that post also mentions corn/corned beef, which has another post.

- skim v skimmed (of milk)

- minced/ground

- mashed & smashed: I've written about mashed potato(es), which BrE can call just mash (now we're back into nouns). A related AmE verbal adjective is smashed. In the Corpus of Global Web-Based English (2013), North Americans have the collocation smashed potato(es); there are none in the British data. The distinction between mashed and smashed is that a smashed potato is less thoroughly mashed—it will still have some (orig. AmE) chunks of potato in it—and may well include the potato skins.

These days, you definitely see smashed on BrE menus—sometimes in front of potato but much more often in front of avocado. This Google ngrams graph shows that smashed avocado (blue line) surpassed mashed avocado (green line) in UK books around 2019, but the phrase has not taken off in the US (red line) in the same way, where people just talk about avocado toast without an adjective. (You hear that in BrE too, but it's not as prominent as in AmE.)

Verbs of placing

- BrE bung: to put forcibly, without delicacy. It's very informal word, but that goes with the vibe of a lot of British cooking shows. The closest equivalents are probably stick or throw (both General English), as in stick/throw it in the oven/pan, but bung feels the most informal and dismissive of the bunch. Here are some Google Image results for "bung it in the oven", which show the phrase applied to simple, quick recipes and the people who cook them:

- BrE tip in means, essentially 'pour in', but it's often used for solids. It can apply to chopped carrots, as in Maryellen's example, because you're assumed to be tipping the chopping board over the pan and 'pouring' the carrots in. The magazine that just came with my grocery order has tip in its first two recipes: bread dough is tipped onto a floured surface. Cooked spinach is tipped into a sieve.

- add: Mrs Redboots suggested this one. Add is General English, of course, but she notes a different usage:

American on-line cooks "add" ingredients to an empty pan. Can you add something when there is nothing there?

- pop: British people are always popping—popping in, popping out, popping to the shops—so I suspected that pop it in the oven would also show up as more BrE, but no. It looks like General English in the GloWbE corpus. Google Books has pop it in the oven becoming more common after the 1990s, with BrE use of the phrase overtaking American from 2014.

- AmE does seem to like to pop open various things, and BrE doesn't so much. This can include food/drink packaging (pop open a beer), but is often used of doors, the (BrE) bonnet/(AmE) hood or (BrE) boot/(AmE) trunk of a car, etc. Pop probably deserves it own post someday.

Verbs of mixing and cutting

- (BrE) blitz: It sounds a bit slangy, but blitz is nearly the standard verb in BrE for using a blender, especially for short blasts—to the extent that some people call any kind of blender a blitzer. (I did not succeed in finding out how common this is, because the data is overrun with people named Blitzer and sports blitzers, etc.). Blitz looks like it might be making it into US website recipes.

whisk: This is general English, but only in BrE (and rarely) have I seen it used to refer to the action of using an electric mixer (with whisk-y attachments). It's thus used a lot more in UK recipes.

a wooden reamer - beat [added 18 Mar 25]: I am looking at two cook(ery) books now, and see that Americans are always beating their ingredients where British bakers are whisking them. Neither word is particular to one nationlect, but the rates of usage seem quite different. (Click for an ngram of beat the eggs.)

- (orig. AmE) rice to press through a holey surface or mesh to create very small pieces; some people have special ricers for this. Especially used with boiled potatoes to make mashed potato(es).

- (AmE) pull: to "stretch and draw" a mixture (usually AmE taffy) until it is aerated and ready to set. OED has this as "chiefly" AmE.

And then there is the pull in pulled pork, pulled chicken, etc. OED has this as "chiefly U.S. in the late 20th century" (but it seems to have come back to the UK with US-style pulled pork). - (AmE) ream to juice a citrus fruit, using a device that you twist in the halved fruit.

Verbs of baking/pastry

- frost/ice: See this old post.

- (BrE) knock up (a crust): to seal and finish the crusts of a pie. (Here's an online discussion of it.) This is no doubt related to uses of the phrase in other crafts. Here's the first OED sense definition for knock up:

To drive upwards, or fasten up, by knocking; spec. in Bookbinding, etc. to make even the edges of (a pile of loose sheets) by striking them on a table; in Bootmaking, to cut or flatten the edges of the upper after its attachment to the insole.

AmE knock up is a more general expression for 'prepare quickly'. So if you knock up a pie (or a three-course meal or anything else) in AmE, that's talking about the whole process of preparing it, from start to finish.

- proof / prove In BrE, you prove dough and (traditionally) in AmE you proof it (unless you've watched lots of GBBO).

Verbs of preserving

- can v tin/bottle: Say you have tomatoes that you blanch and put into jars for use later in the year, in AmE that would be canning even though the tomatoes are going into a glass jar. You could also talk about canning if you were putting things in a jar to pickle, I think—it's just our general word for what to do when you have a glut of some fruit or vegetable that needs saving for later. The OED suggests tin (for putting things in metal containers) and bottle as BrE equivalents, but I think maybe for putting things in jars more general-English words like preserve and pickle might be more used? (Let us know in the comments.) Bottle would be used in AmE if you were putting things, like sauces or liqueurs, into bottles, but not usually for jars.

Verbs of meat preparation

- French: this one (not in my vocabulary) I got from the OED:

transitive. Cookery (now chiefly U.S.). To prepare a joint by partially separating the meat from the bone and removing any excess fat.

- tenderize orig. AmE, but has been in BrE since the 1970s

...no knickers

The more common phrase--never applied to me because of my fondness for wool--is all fur coat and no knickers. Both phrases are used to refer to someone (or something) that is all flash and no substance. That is, one who's bothered with the decorations, but not with the basic necessities, like knickers (=AmE panties).

Of course, the moralistic edge of the phrase--encouraging us to have a good foundation (garment) before turning our attention to frills, is often these days overlooked, in favo(u)r of the ol' nudge-nudge, wink-wink. Search (unfiltered) all fur coat and no knickers on Google Image to see what I mean, if you need to. But you don't really need to, do you?

Another faintly misogynistic (which is not to say entirely unuseful) phrase that the British have introduced me to is mutton dressed as lamb: used to refer to any woman who is unflatteringly dressed in a style that is deemed too young for a woman her age. Better Half also enjoys the phrase mutton dressed as mutton, which is to say a woman who is unflatteringly dressed in a way that is too appropriate to her age. (Thankfully, neither of these has yet been applied to me...to my face.)

The British do not have a monopoly on phrases that pass judg(e)ment on the sartorial choices of women. Muffin top, to refer to the roll of flesh that often appears at the top of some low-slung trousers/pants is an Americanism. This word has made its way into BrE, even though the types of muffins that the phrase alludes to are a fairly recent import to the UK.

[Here I must digress. The cake-like American-style muffin seems to have taken over the UK. This is the kind of muffin that a lot of my students think of first when asked to describe muffins--which they are often asked to do in my courses--rather than the type of flat, non-sweet thing that looks like what Americans call an English muffin, but which actually differs from those as well. According to United Biscuits, individually packaged muffins, such as those pictured at the right, are now 'the second largest sector in eat-now cakes' in the UK. But...there has been some semantic slippage in the transfer of this term (and baked good) to the UK: (a) The muffins that are sold in the UK as American-style muffins often lack 'muffin tops' --i.e. the mushroomy bit that has risen over the side of the muffin tin-- so I'm not sure whether the phrase muffin top is quite as evocative here when applied to love handles. I've yet to come across a home-baked muffin in the UK that wasn't made by me--though one can buy Betty Crocker blueberry muffin mix at Asda, I see. (Not that I want to admit to having been in an Asda--which is owned by Evilmart.) (b) Many of the so-called muffins I see in UK shops are, in AmE terms, cupcakes, as far as I'm concerned. One started to see (horrors!) chocolate chip muffins in the US when I was in my late teens, but to my mind, muffins have to have some whiff of healthfulness about them--bran or fruit, or at least cornmeal--and certainly no frosting. Something built around the theme of a chocolate bar, such as the Galaxy muffin above, is most definitely a cupcake. And before raising the issue of fairy cakes or otherwise taking this conversation any further on the baked goods tangent, please do have a look at the baked goods post from July.]

[Here I must digress. The cake-like American-style muffin seems to have taken over the UK. This is the kind of muffin that a lot of my students think of first when asked to describe muffins--which they are often asked to do in my courses--rather than the type of flat, non-sweet thing that looks like what Americans call an English muffin, but which actually differs from those as well. According to United Biscuits, individually packaged muffins, such as those pictured at the right, are now 'the second largest sector in eat-now cakes' in the UK. But...there has been some semantic slippage in the transfer of this term (and baked good) to the UK: (a) The muffins that are sold in the UK as American-style muffins often lack 'muffin tops' --i.e. the mushroomy bit that has risen over the side of the muffin tin-- so I'm not sure whether the phrase muffin top is quite as evocative here when applied to love handles. I've yet to come across a home-baked muffin in the UK that wasn't made by me--though one can buy Betty Crocker blueberry muffin mix at Asda, I see. (Not that I want to admit to having been in an Asda--which is owned by Evilmart.) (b) Many of the so-called muffins I see in UK shops are, in AmE terms, cupcakes, as far as I'm concerned. One started to see (horrors!) chocolate chip muffins in the US when I was in my late teens, but to my mind, muffins have to have some whiff of healthfulness about them--bran or fruit, or at least cornmeal--and certainly no frosting. Something built around the theme of a chocolate bar, such as the Galaxy muffin above, is most definitely a cupcake. And before raising the issue of fairy cakes or otherwise taking this conversation any further on the baked goods tangent, please do have a look at the baked goods post from July.]Back to American body-fascist misogyny! Or cultural observation...take your pick! The other AmE phrase that springs to mind (though admittedly not as widespread as the others discussed so far) is sausage casing girl, to refer to someone young and female who wears clothes in a size or two smaller than the sizing lords intended. I learned this phrase from an LA Times article this summer, and it did strike me as descriptive, though cruel. The article seems to no longer be accessible to the masses on-line, but you can read Grant Barrett's record of it here.

All of these expressions describe phenomena that exist in both countries, but the two cultures have had different priorties as to which type of woman gets judged on the basis of her behavio(u)r with reference to her appearance. As ever, we can wonder about what this says about the cultures--although one has to be careful about plucking a couple of phrases out of the culture and judging the culture on the basis of those. Nevertheless, in the spirit of sweeping generali{s/z}ation, we see in (some of) these phrases British women being mocked for not acting their age and American women being mocked for not acting their weight. And men on both sides of the Atlantic remaining relatively unscathed.

pronouncing words from Spanish

There are two obvious reasons why American and British English speakers pronounce Spanish words differently when they need to pronounce them in English, and these result in different kinds of differences between AmE and BrE Spanish pronunciations.

The amount of Spanish in the US means that even the most monolingual Americans hear and see quite a bit of it. If you went to Mass at 9:00 in my little northeastern hometown, you heard it in Spanish. (No big deal worship-wise if you consider that a decade before I was going to Spanish Mass, everyone was hearing their Mass in Latin.) If you go for fast food, you might need to know what pico de gallo is. It's natural to me as an American to pronounce a double-L as a 'y' sound if I see a word that ends in a or o. One of the hardest things for me to learn in South Africa was to 'granadilla' as gran-a-dill-a even though I so wanted to say gran-a-deeya. (Never had to pronounce it in the US—we say passion fruit.)

And I've yet to hear an Englishperson say the edible salsa without the first syllable rhyming with gal. (I seem to recall hearing some BrE speakers use a more 'back' vowel in the dance salsa, but still use the more 'front' vowel in for the condiment.) At Dialect Blog there are other examples: paella and cojones. Maybe the food pronunciations will change soon. "Mexican street food" (which is considered to sound nicer than "Mexican fast food") is the big new-restaurant trend in Brighton these days; I counted three newish burrito places in a quarter-mile radius last week. But maybe this won't matter. No one seems very bothered about finding out the Thai pronounciations of any of the Thai dishes we've been scoffing/scarfing here for the past decade.

Of course AmE pronunciation of Spanish is not Spanish pronunciation. It's just a bit more Spanishy than BrE pronunciation, much of the time. One doesn't, for example, roll the 'r' in burrito in AmE.

The best example of unSpanish UK Spanish pronunciation, though, was pointed out to me by a New Yorker in the UK, who was amused by Brightonian pronunciations of the Spanish island Ibiza. The pronouncers in question were studiously lisping the 'z', but pronouncing the first syllable with a very un-Spanish 'eye' vowel. Britons seem to be very studious about lisping esses in Spanish words.

Please add your examples in the comments. And Spanish speakers, I want to know: can you tell the difference between a British and an American accent when we attempt to speak Spanish?

Some other items business (read: self-promotion) before I go:

- I'm in the latest Numberphile video, talking about math vs maths (again!). Have/take a look!

- I'll be giving my 'How Americans Saved the English Language' talk at Tunbridge Wells Skeptics in the Pub on the 4th of July. Expect (verbal) fireworks! And cake!

- If you're on Twitter, I'm there, of course, giving a Difference of the Day five days a week and lots of links to Britishy-Americany-Englishy-language-y things. I also give a much smaller number of links via my Facebook page, so 'like' it if you'd like to get the occasional bit of news from me in your pages feed.

(h)erbs and (h)aitches

[Update, 14 June 2006: As is often the case, Americans have the older form of the word--the British used to say 'erb too. It just happened to be mentioned in the Guardian's Weekend magazine this week. See Michael Quinion's World Wide Words for more...]

[Update, 3 September 2014: I've now done a proper post on herb.]

A common response to an American pronunciation of herb is: "Are you a Cockney, then?" Dropping aitches is a definite marker of lower social class--and these days it's fairly rare. In fact, aitches get inserted sometimes in the name of the letter, i.e. haitch. This is heard in the semi-humorous admonision to not 'drop your haitches' (and thus sound 'common'), but is heard unironically in many people's everyday speech, although it is not considered to be 'standard' usage. The story is that it's the Irish pronunciation, and I've read in various places that haitch marks Catholics in Northern Ireland and the Catholic-educated in Australia. I've noticed no such associations here, and neither have friends of mine, though one did suggest that it might be a marker of region rather than religion here. Indeed, my haitch-saying friend is from Liverpool, whose dialect (Scouse) is influenced by Irish immigrants.

As long as I'm talking about herbs...there aren't many that differ in name between the US and UK. Americans call the green part of the coriander plant cilantro, while the British call it coriander. Americans use coriander to refer to the spice made by drying and grinding the plant's fruit. Presumably the difference exists because Americans were introduced to the herb in Mexican cooking, whereas the British know it from South/Southeast Asian cooking. Once, reading a British recipe in Texas, I got confused. I knew that British coriander wasn't meant to refer to the powder in my coriander jar, but could only remember that the American translation also started with C. So I put a whole lot of cumin into my chicken soup. I ate about three bites before I decided that there was nothing to do but toss it out.

Oregano differs in pronunciation, with Americans saying oREGano and the British saying oreGANo. In South Africa (where I first started picking up 'commonwealth English'), they use oreGANum.

As for other herbs and spices, I have been asked "Why do Americans put cinnamon on EVERYTHING?" I can only answer (ignoring the hyperbole): "Because it's tasty."