So last time,

I wrote about disease versus infection following the phrase sexually transmitted, and I started thinking (again) about how we talk about medical things--technical or non-technical? In the book I'm writing (for

you!), I've touched on it a little with respect to bodily functions:

Sitting in my doctor’s waiting room, I’m amused and a bit astonished to find posters about what to do if there is blood in your pee or poo.* The equivalent American public-service advertisements say urine and stool. In the medical context, America avoids being crude by sounding more scientific, and Britain uses baby-talk.

* Make an appointment with your doctor immediately!

The discussion hits on things like BrE

waterworks ('urinary tract') and

back passage ('rectum') and

classes given to foreign nurses in the NHS on British slang--

aka British euphemism. (It's a bit of the book that looks at the stereotype of Americans as euphemists, so yes, there's a lot of attention in the other direction.)

The "Americans use overly technical terminology" aka "Americans like jargon" stereotype that I contribute to in the quote above is one worth taking apart as well. I've been encouraged in that stereotype when I hear friends talk about their

chest infections where I tend to have

bronchitis. But then they're also talking about having

cystitis (my poor, unhealthy friends), which I hadn't heard of before moving here. An infected cyst? Ew... No, it's a bladder infection. In AmE I'd call it a

UTI (

urinary tract infection). (The NHS website tells us that cystitis is a common type of UTI, so the terms are slightly different--but that's the case with

bronchitis and

chest infection too.)

So far, we're tied:

Itises: BrE 1, AmE 1.

Infections: BrE 1, AmE 1.

So I thought I'd have a look at which things Americans and Brits call

infections and which they use Medical Greek

-itis names for.

The tables below are the statistically "most American" (left) and "Most British" (right) nouns that come before

infection in the

GloWBE corpus. (If you click on the table, it should get bigger.)

|

| "Most American" and "Most British" words preceding infection |

What you can notice there (if you can read the small print)

is that the "more British" preceding nouns include

things that

can get infected (wounds, chests, throats), whereas the "more American"

ones tend to be

the microbes that do the infecting. In AmE, I think I'd

say someone has an

infected wound rather than that they have a

wound infection. And one kind of wound infection you can have is a

staph infection (in the US list), which is a very familiar term from my AmE childhood (we were constantly being told that gym mats were very dangerous). I don't know that I've ever heard

staph infection in the UK.

In the BrE column you can also see

urine infection, another BrE way of saying

urinary tract infection. This one names neither the pathogen nor the organ, and always strikes me as a bit odd. Urine might have germs in it, but can urine itself be infected?

BrE has more

throat infections because Americans are more likely to say they have

strep throat. In my experience,

scarlet fever is heard more in BrE these days (which is not to say you never hear it in AmE). When my child was diagnosed with it (in the UK), I really felt like I'd been taken back to Victorian times. She wasn't all

that sick. But when I looked it up and found that it's the strep germ, I thought: maybe you hear

scarlet fever more often in UK because AmE has

strep infection.

Some of the numbers up there, though, are art{e/i}ifacts of the corpus. AmE has 56 instances of

HSV infection but all of them come from a single website (virologyj.com), so we shouldn't take too much from that. American, like British, English would typically call that

herpes. HBV infection is found on a greater range of sites, but they are mostly medical journals and such. Laypeople would generally say

Hepatitis B.

But that does seem to sum up the difference between the AmE table and the BrE table: a lot of the AmE

infection cases are use of medical jargon in a medical context--

staph infection was the only one I knew as a layperson. Whereas in BrE the body-part+

infection cases are terms that non-medical people would use when talking about their maladies

.

If we look at the

infections that American and British English

have in common, we can see that Americans do talk about infections too, sometimes with body parts, even.

But what about

-itises? Is it mostly Americans using the fancy words? No, but there again maybe some effects here of one source being over-sampled in the corpus. Here I'm showing what came up as 'most American' (left) and 'most British' (right), with a bit of the 'neither one nor the other' showing in white. This is going to be very hard to read on a phone (sorry!), but I'll write up the highlights below.

I've given a comment in red if (a) the things are not diseases, but just coincidentally spelled with -

itis, or (b) if it's a spelling issue. Though

oesophagitis shows up in the British list, it's not because Americans don't use an

-itis name for the problem, but because we spell it

esophagitis. (

Click here for my old post on

oe/e spellings.) The British list is lengthened by a misspelling of

arthritis and having two spellings for

tonsil(l)itis.

After discounting those, the British list is still a lot longer than the American one, but I'm very much suspecting some bad corpus effects here.

Tonsillitis,

colitis, dermatitis, gastroenteritis, appendicitis, pancreatitis--I or members of my family have had all of these and that's just what they were called in the US. The numbers for these diseases are greater than expected in the British part of the corpus--but they're hardly absent in the American part. For example, note that there are 756 AmE occurrences of

meningitis--which is here counting as "rather British", while only 16 AmE hits for

phlebitis make it "very American". Some of these cases are going to seem "more British" or "more American" to the software just because the corpus happened to hit on some websites that talked about these things a lot. But I think what we can say from this exercise is that

we have no particular evidence for British English avoiding -itis words, despite its greater use of body-part+infection.

Still there are a few

itises worth mentioning for BrE/AmE interest. One is

labyrinthitis, which I had an unfortunate encounter with this spring. When I described my symptoms (the room going upside-down and inside-out every time I turned my head left), lots of British friends said "Oh, that's labyrinthitis. I've had it. It's horrible!" But it was not a word that my American friends seemed to have at their fingertips--to them it was an

inner-ear infection. (Why do Brits seem to get it more often, though?)

Conjunctivitis shows up on the British list, though it is a word that Americans use too. But Americans have another informal term for the problem:

pink-eye. That will push the US

conjunctivitis numbers down. (There are a few UK hits for

pink-eye--with or without the hyphen, but a lot of US hits.)

In the white part of the table--where the numbers are similar for AmE and BrE -- are the two

itises that are earlier in this post:

cystitis, which I've experienced as more British, and

bronchitis, which I've experienced as more American. Because the corpus is imperfect, I'm not going to totally discount my experience on these. But it would be interesting to hear if others (particularly transatlantic others who can compare) think I'm off my rocker...

I was surprised to see only one made-up disease in the list:

boomeritis on the AmE side. (It was the name of a book--click on the word to learn more.) I would have bet that (AmE)

senioritis would appear. (As it happens, there were only two US examples of it in the corpus--most are Canadian.) To quote

Wikipedia:

Senioritis is a colloquial

term mainly used in the United States and Canada to describe the

decreased motivation toward studies displayed by students who are

nearing the end of their high school, college, and graduate school

careers.

For a minute there, I was worried that I expected

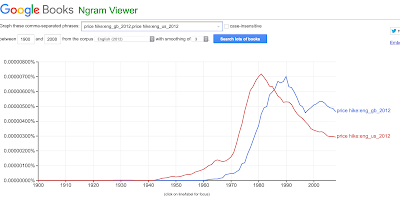

senioritis to be there because I am OLD and UNCOOL. But I'm happy to report that in both the Corpus of Historical American English

and in Google Books, the rate of

senioritis use has only gone up in the decades since I was a high-school/college

senior. Not happy for the teachers who have to teach these seniors, but happy that my vocabulary is not a complete dinosaur--yet.

If you're interested in other disease names, do have a look at the

medicine/disease tag--thanks to (a) having a small child and (b) being a complete hypochondriac, quite a few have come up over the years--but there are still many more to cover in future.